When John Sperling started the University of Phoenix in 1976, there was nothing new about profit in higher education.

For-profit schools have their roots in Colonial America. There weren't enough places for people to get formal education, so entrepreneurs started teaching practical skills and trades, as well as reading and writing.

"Many of these [entrepreneurs] were clergy who weren't paid very much and had to supplement their income," says Richard Ruch, author of Higher Ed, Inc.: The Rise of the For-Profit University. Clergy were the educated class. "So they would offer classes in their homes or in the parsonage or in the church and charge a fee," says Ruch. Often their wives would offer classes, too, in skills such as sewing and weaving.

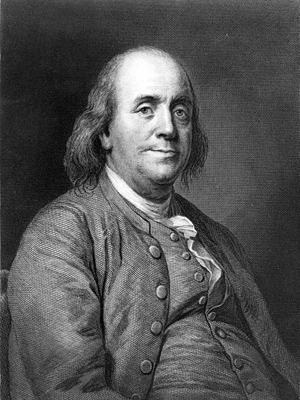

Benjamin Franklin was one of the early champions of for-profit schools. "Franklin himself was largely a product of self-education and the system of apprenticeship brought over from Europe," writes Ruch in his book.

Franklin was constantly fighting the "Latinists," whose ideas about education were based on the British models of Cambridge and Oxford. "The early American colleges devoted themselves almost entirely to the teaching and study of theology, Greek and Latin languages, classical literature, and philosophy," Ruch writes. In 1723, nearly 60 percent of the books in the Harvard College library were about theology, and only two books were about commerce, according to Ruch.

Franklin believed the new nation needed a new approach to education. He wanted people to learn skills and trades to help build the economy. He lamented in his journals that so many of his contemporaries had "an unaccountable prejudice in favor of ancient customs and habitudes."

For-profit schools grew in response to demand. They taught things such as surveying and navigation. As the economy developed and changed, for-profits offered new trades and skills such as bookkeeping, engineering and technical drawing. The schools "played a particularly important role in opening up education to women, people of color, Native Americans, and those with disabilities, especially blind and deaf people," writes Ruch.

For-profits were for people who could not get access to America's traditional colleges and universities, and they offered a kind of career training that was not available in those schools. For the most part, these "career colleges" offered certificates and sometimes associate's degrees, but they didn't typically offer bachelor's degrees. In the early 1970s for-profits enrolled just 0.2 percent of all degree-seeking students in the United States. They were "such a small component of the postsecondary world that most of us didn't even think of them," says Bill Tierney, a professor of higher education at the University of Southern California. "Then along comes John Sperling and the University of Phoenix."

The success of the University of Phoenix changed everything. Phoenix proved that higher education could be big business in America. When John Sperling took his university public in 1994, several other for-profit schools soon followed -- many of them small trade schools that had been around for decades.

In 2012, about 12 percent of American college students attend for-profit schools. The vast majority of them go to schools that are operated by large, publicly traded corporations like the University of Phoenix.