Tromping through the wet grass in muddy rubber boots, Portland State University senior Tammy Rodriguez leads a group of five curious third-graders to the edge of a vegetable plot. Rodriguez bends down to pull a green leaf from a plant, tears it into strips and hands samples around.

"This right here is collard greens," she tells them. "You can eat the stem, you can eat the little leaves and the flowers. Try it and if you don't like it you can discreetly turn away and spit."

Without hesitating, a boy in a grey hooded raincoat pops the leaf into his mouth. "It tastes like broccoli!" he declares in surprise.

"You know why it tastes like broccoli? It's part of the same family. It's the Brassica family," Rodriguez replies.

It's doubtful the boy will hang onto the Latin. But for a city kid, eating a raw plant in the middle of a rainy farm field is pretty memorable.

Rodriguez and about a dozen other students from Portland State University (PSU) are teaching schoolchildren about growing and eating vegetables as part of a class in PSU's liberal arts program. The college students volunteer at the non-profit Sauvie Island Center, about 10 miles northwest of Portland, which holds field trips to its farm for elementary school children from the city. The PSU students are all in a senior-year capstone class designed to link college students with local nonprofits, government agencies and businesses.

As the name suggests, the capstone program is meant to finish off a student's four-year college experience by applying skills they've learned in class to real-world problems. It's more than an internship, because the work is done by all 15 students in the class, working together.

PSU is a recognized leader among public universities that are trying to transform the way they teach the liberal arts to make undergraduate education more relevant and engaging to both students and the community. A growing number of colleges and universities across the country - both public and private - have adopted civic learning programs and other approaches to liberal arts instruction that connect "ideas with action," and represent what one former University president calls a "necessary revolution" in undergraduate education.

Rodriguez's capstone course is Hunger in the City: In Search of Community Food Security. It fits both her academic and her personal interests. Rodriguez, 50, lives with her husband on a small farm and works part time as the education director for a nearby farmers market.

"That's the thing about the capstones," Rodriguez says. "It gives you some real-world experience. For me, doing what I wanted to do. For the others, it just got them out in the community to realize what really is out there."

Opening the Ivory Tower

Portland State is Oregon's largest public university. Its campus in downtown Portland serves some 30,000 students. It's mostly a commuter school; 90 percent of the students live off campus, and only half of them are fulltime students. PSU has a high percentage of adult learners and students who are working their way through school. Many are the first generation in their family to attend college.

In the early 1990s, PSU began to overhaul the way it taught general education courses - the classes that all undergraduates are required to take regardless of their majors. They include liberal arts courses like writing, speech, social sciences, math and introductory sciences. Traditionally, undergraduates spent their first two years of college picking away at these general education requirements before declaring a major.

PSU Provost and Vice President for Academic Affairs Roy Koch says the old system wasn't working. Too many students quit after freshman year. Too many others weren't learning as much as they needed to learn. It was time to reshape the liberal arts to meet modern market demands.

The most significant reforms boil down to shifting how authority is delegated within the university and within the classroom. In the old days, general education classes were taught within the traditional academic departments. English professors taught composition, history professors taught history, but the classes had little to do with each other.

"It was a kind of salad bowl approach to education," says Yves Labissiere, assistant director of the program. Different disciplines got tossed together in a student's academic bowl but didn't blend very well.

So PSU created a University Studies program where all of the general education courses are taught, and where classes are clustered together around large intellectual themes. The new model at PSU draws professors out of their departmental silos. The goal was "getting faculty from the disciplines to come together and structure the curriculum around big questions and higher-order thinking skills," Labissiere says.

The other broad change was a new emphasis on students learning from each other. Lecture courses by a pontificating professor were discouraged. Students started leading discussions more.

PSU instructor Vicki Reitenauer has been teaching capstones in the University Studies program since 2000. Her field is women, gender and sexuality studies. She likes the program, but she says some of her colleagues prefer to teach courses that aren't part of University Studies. Some question the level of rigor in the University Studies program. And many professors in traditional academic departments still run their classes as lectures.

"Programs like this are deeply threatening to institutions, including this one," Reitenauer says. "If we recognize that there are ways of reaching students that are different from the expert standing at the front of the class, that really changes the game. Changes the balance of power."

PSU's University Studies program has four fundamental qualities it wants students to graduate with: the ability to think critically; effective communication skills; an understanding of the diversity of human experience; and a deep sense of civic responsibility. With a few word changes here or there, these are pillars of most liberal arts programs in the United States today.

The University Studies website says little about preparing students for the job market - after all, it's still a liberal arts program and not a vocational school. Instead, PSU stresses the relevance of liberal training in the service of community. The motto of Portland State is: Let Knowledge Serve the City.

"I think we're just getting to a place in our society where our problems are becoming so complex that we certainly need that strong, academic book learning," says PSU Capstone Program Director Seanna Kerrigan. "But we also need that application-based [learning] to show the complexity of the problems, rather than simplifying them into case studies or simple research papers."

Inquiry Program

First-year PSU students take a year-long Freshman Inquiry program, a sequence of courses on a specific theme taught by a interdisciplinary team of instructors. Themes offered in 2011-12 include Ways of Knowing, Design and Society, Globalization and Sustainability. There's an emphasis on students helping lead the discussion and on learning from each other.

University Studies Assistant Professor Leslie Batchelder once taught a Freshman Inquiry course called Cyborg Millennium, about how technology is changing human experience. (Cyborgs are beings with both artificial and biological parts.) Batchelder co-taught the course with a scientist. He handled the math and science. She covered writing, literature and film. Historically, this kind systematic, interdisciplinary teaching has been relatively unusual in American higher education.

Batchelder says some of her colleagues hate teaching the freshman classes. "It is the hardest teaching you'll ever do," she says, "because you have to teach outside your comfort zone."

Another goal of the year-long freshman course is to help create a sense of college community that would otherwise be hard to achieve at a commuter college. At a residential school, dorm life is one way people form social groups. The 35 students in a given Freshman Inquiry class don't do laundry together, but they still see each other week in and week out.

Second year PSU students take three one-term Sophomore Inquiry courses. They also begin taking upper-level courses clustered around the Inquiry program but taught in traditional academic departments such as history, anthropology and philosophy.

A key part of the University Studies program are peer mentors. Graduate students and upper level undergrads are hired to sit in on the Inquiry classes and then work with small groups of students in separate discussion sessions. Mentors help with homework and writing, how to navigate the university, and even how to handle life.

"You're with these students, at least at the freshman level, for a whole year," says Jacob Sherman, a mentor and a graduate student in education. "So you really get to know them on an individual level. And students will come to you with things they would never come to with a professor. To talk about drinking problems, relationship problems. The mentor is there to help that student and also plug the student into other resources on campus, such as counseling."

Capping it Off

The capstone program is meant to bring a student's academic experience full circle, returning to the kind of interdisciplinary work started in the Freshman Inquiry course. PSU offers some 240 capstone classes a year to about 3,800 students.

"It's a final opportunity to be in a classroom with students from other majors, to learn how to work in an interdisciplinary team," says Capstone instructor Celine Fitzmaurice. "If you leave PSU and you're working in a job with a writer and an engineer and a marketing manager, you will have the skills to work and communicate and create something as a team. Whether it's in service to your company or to larger society."

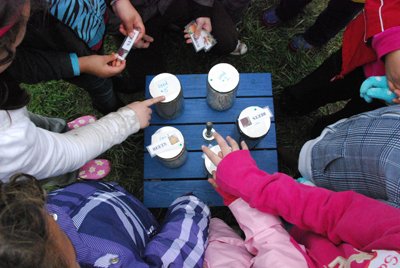

In a PSU classroom filled with tables and computers, seniors in the Hunger in the City course are working on projects that will be a big part of their term's grade. Some huddle with Fitzmaurice and Sauvie Island Center director Anna Goldrich to go over learning assessments the students have designed to give third-graders after their visit to the organic farm.

Third year sociology major Mickey Sarkar spent time at the farm teaching children about bees, butterflies and other creatures involved in pollination. She says it was good to be in a class with students majoring in a wide variety of subjects, not just her own. It was also the first time she taught children.

"I was definitely hard," Sarkar says with a laugh. "Every Thursday, being out there in the freezing cold and the rain for about five hours with crazy children. But I think I got a lot out of it."

Sarkar, 25, chose the Hunger in the City capstone for practical reasons. She works at a gourmet grocery store and can only attend school certain days of the week. The hunger capstone fit her calendar. "I looked it over and thought, that sounds pretty fun," Sarkar says.

Senior English major Jean Woest was not so enthused. He took the hunger course because he needed the credits. He would have preferred a more traditional way to end his academic career, such as writing a thesis paper about literature. For the capstone, Woest wrote up the findings of a survey he did with two other students on community gardens in the Portland area.

"When you're at the end of your program of study and you've gone through all this laborious effort to learn about a certain area, to have another thing thrown at you where you have to divert is a little bit frustrating," Woest says.

For senior Tammy Rodriguez, the interaction with other students in the hunger capstone was rewarding. Even better was learning how many food-related nonprofits there are in the Portland area. "It opened up a whole new world," Rodriguez says. "It guided me to where I want to be." Instead of looking for work in public health, as she first planned, Rodriquez is studying for a master's degree in education. Her focus: hands-on, land-based sustainability education, maybe even on her own educational farm.

A National Movement

The reengineering of general education at PSU was part of a larger evolution in general education and liberal arts programs across the country. This movement has been fueled, in part, by the work of the Association of American Colleges and Universities (AACU), a group of more than 1,200 institutions working to improve undergraduate liberal education. The AACU has pushed liberal arts programs to reject their traditional, non-vocational identity and embrace the practical value of a liberal arts education in modern life.

AACU President Carol Geary Schneider writes that the goal is to recast liberal education "no longer as an option for the fortunate few, but rather as the most practical and powerful preparation for 'success' in all its real-world meanings: economic, societal, civic and personal."

Back in the 1960 and 70s, when liberal arts programs were at a historic peak of enrollment, many students had abstract reasons for going to college, says University Studies professor Leslie Batchelder. "People still had this notion of opening your mind and improving yourself and being a well rounded citizen," Batchelder says. "[College] was a lot cheaper then. [Today's] students, rightly so, don't exactly have these lofty ideals. It's more like, how can I get through this paying the least amount of money?"

Portland State University Provost Roy Koch says the freshman dropout rate has dropped by more than 10 percent over the past two decades. He says that's a sign that the University Studies program has been successful. But he'd like to see the freshman retention rate - now at 70 percent - go higher.