Chris Barbic started the YES Prep Public Schools out of frustration.

He was a sixth-grade teacher at an elementary school in Houston that served mostly low-income students from Hispanic families.

"My second year of teaching, my kids who I'd taught in sixth grade started coming back and visiting and telling me stories about the quality of the education they were getting in the middle school, the environment in the middle school," Barbic says. "It was story after story of great kids, who really wanted something better, whose families wanted something better, just absolutely not getting what they needed."

Several of his former students ended up dropping out of school and "joining gangs, getting pregnant, doing all the things that the other kids in the middle school were doing."

Barbic says he faced a choice. "Quit teaching because I was going to be banging my head against a wall for the rest of my career," or create a new school where kids would have a better chance at success.

Barbic started YES in 1995. YES stands for Youth Engaged in Service. The goal from the beginning was to prepare students for college. The idea is that low-income students can better serve their communities if they get college degrees.

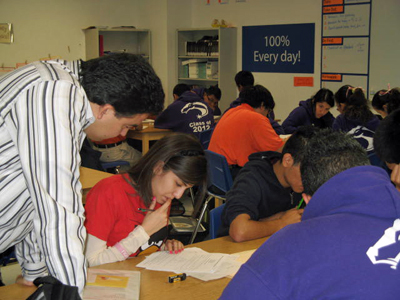

YES Prep now serves more than 5,000 students in grades six through 12 at 11 public charter schools. All of the YES schools are in Houston, Texas. Students are admitted by lottery and there is a waiting list to get in. Most of the students are from low-income families and 95 percent are Hispanic or African American. Almost all of the students will be the first generation in their family to go to college.

The Hypothesis

YES Prep is organized around a core belief.

"If you give kids from low-income backgrounds access to the same opportunities and resources that kids get in great private schools and in great suburban schools, [they] can achieve at the exact same level," says Barbic.

Only 9 percent of America's lowest-income students get bachelor's degrees by the time they're 24 years old. Students from the highest-income families are almost 10 times more likely to earn a bachelor's degree by the same age.

Research on college completion indicates there are several major risk factors for dropping out of college. They are:

- having parents who did not complete college

- being low-income

- having to work while in college

- going to a college that has a high dropout rate

- not going to a good high school

Of all these risk factors, Barbic and his colleagues knew they couldn't do anything about the first two.

They might be able to have some impact on the third by helping students get good financial aid packages that would allow them to not work, or work less, while in college.

They could do something about the fourth factor by steering as many of their students as possible to good colleges.

And they had complete control over the last factor. If they could create really good high schools where the classes were rigorous and the expectations were high, they might be able to go a long way in fixing the college completion problem among at least one group of students in Houston, Texas.

The Results

Barbic and his colleagues succeeded in creating top-notch schools.

A big focus has been Advanced Placement classes. The AP program is sponsored by the College Board, an organization that creates and scores standardized tests. Advanced Placement classes are designed to prepare students for college, and students who score high on AP exams are typically awarded college credit by participating colleges and universities. Only 18 percent of American high school students pass at least one AP exam. At YES Prep, nearly half the students pass one.

YES has had similarly impressive results with the SAT, an entrance test required by many colleges. Student SAT scores tend to correlate directly with family income. The higher your family income, the higher your SAT score tends to be. But at YES, where most of the students are from poor families, close to 70 percent of students score as well on the SAT as students from middle-income families, and they score significantly better than other minority students in America.

Perhaps the most telling statistic is this: Less than 10 percent of YES Prep alumni take remedial classes when they get to college. Nationally, as many as 60 percent of incoming college students have to take some sort of remedial class.

The bottom line is that YES Prep has succeeded in its goal of preparing students for college. Based on academic preparation alone, one could reasonably expect that 80 or 90 percent of the students would graduate from college.

But that didn't happen.

The College Graduation Problem

With the exception of a few who go to the military or on religious missions, all of the YES Prep graduating seniors go to college.

But only 40 percent of those who graduated from high school at least four years ago have actually completed a college degree. Twenty-eight percent left college without a degree. And the rest are still in school, years after they should have finished.

The results have been a shock to teachers and administrators at YES Prep.

"I think that with [our] first graduating class we thought, 'OK, we've done our job,'" says YES Prep's Jennifer Hines, who's been a teacher and administrator at YES since 1998. "Here, colleges, have some really wonderful kids. Here, kids, have some really wonderful college experiences. And that didn't work."

Now YES Prep is trying to understand why it didn't work -- and what to do about it.

It's a question experts and educators across the country are grappling with, too: Why do so many low-income students quit college? YES Prep's experience promises to shed new light on this question.

The Support System Disappears

The way YES Prep has gotten its students prepared for and into college is to provide them with a lot of support.

The teachers "wouldn't let you give up no matter what," says Raven Rathers, who graduated from YES in 2011 and is now a student at Lamar University in Beaumont, Texas.

"If you're not doing well in a class [the teachers] will say, 'Hey, you're not doing well,'" says Tracy Edwards, a YES Prep parent. "In a regular school" teachers don't do that, says Edwards. "You don't have anyone to come and say, 'Come do these tutorials, let's retake this exam.'"

In addition to intense academic support, YES provides support with the college application process. Applying to college is complicated, and if no one in your family has been through the process it can be particularly daunting and intimidating. Roberto Martinez, senior director of academics at YES Prep, says the parents of YES Prep students want their kids to go to college, "but they don't necessarily have the tools, resources, [or] know-how of how to make that happen."

Juniors and seniors at YES take yearlong seminars where they learn to write entrance essays, fill out financial aid forms and practice for the SAT. They also go on college visits; YES estimates that every student visits at least 20 campuses before graduating.

Most high schools don't do this. Many high schools don't even provide basic college counseling services. It's up to the students -- and their families -- to do it.

"My parents drove me all over New England," says YES Prep's Jennifer Hines. "They knew where the colleges were, they weren't afraid to go there, they had a car that would get them there. They were able to talk about what it was going to be like for me to go away. And that gave me an incredible advantage."

YES Prep's goal is to give its students a similar advantage.

But here's the problem with that approach. When YES students go to college, the support system that helped get them there is suddenly gone. Students who have been relying on their families still have their support system in place.

YES Prep alumna Angela Guerrero describes the experience of losing the YES support system this way: "Once you get to college, yes, you've achieved the YES Prep mission to go to college. But what's next?"

Guerrero couldn't turn to her parents for help with anything; in fact, her father didn't even want her to go to college, and after just one semester away, he made her come home.

Alumni Support

What YES Prep is recognizing is that its students need a support system not just to get into college, but to stay there.

So YES has hired two people to work full-time on alumni support. Chad Spurgeon and Tenesha Villanueva spend their time doing conference calls and Facebook check-ins with YES students on campus. At some campuses where there are several YES alums, Spurgeon and Villanueva have appointed alumni leaders who are responsible for keeping up with the other YES alums and alerting YES if a student is having a problem.

"We get a lot of calls about financial aid," says Chad Spurgeon. YES students rely on good financial aid packages to make college possible, and there are often snags with paperwork or other complications with the financial aid process.

Spurgeon says a small financial aid problem is sometimes enough to cause a student to drop out.

If a YES student has a financial aid problem, Spurgeon might pick up the phone and figure out who is the best person on campus for the student to talk to. "We want to avoid, as much as we can, actually making that phone call" to resolve the issue, says Spurgeon. But he sees his job as similar to what a concerned parent would likely do for their own child: make sure the problem gets fixed.

The Role of Colleges

The fact that Chad Spurgeon and Tenesha Villanueva work for a public school system and provide intensive support to college students is unusual. As far as they know there are no other high schools providing this kind of alumni assistance.

Some people argue that colleges should be providing the support.

"We don't have control over the colleges, though!" says Villanueva with a laugh.

She says most colleges don't have the resources to provide the kind of support YES students need.

"They're working with a broader mass [of students] than we are," says Villanueva. "They're working with students like our students" and they're also working with students whose "fathers went to college, and their fathers' father went to college."

She says colleges and universities, especially large ones, tend to have a "one-size-fits-all" approach to student support services. "We have to specialize for our students," says Villanueva.

In addition, YES is stepping up its efforts to get students to go to colleges where they are most likely to get good support on campus.

In YES Prep's experience, this often means private colleges. While just under half of all YES students go to private schools, 70 percent of YES alumni who have finished degrees went to private colleges or universities.

YES is now creating partnerships with several private colleges where school leaders believe YES students have a better chance at success. One of these schools is Washington and Jefferson College in Washington, Pennsylvania.

Washington and Jefferson -- also known as W&J -- is a small, liberal arts school just outside Pittsburgh. It has 1,500 students; about 80 percent of them are white.

Dean of Admissions Al Newell says a partnership with YES is a good way for W&J to increase its diversity with minority students who are well prepared for college. W&J promises to provide YES students with generous financial aid packages and to support them through college graduation.

There are currently eight YES Prep students at W&J and four more beginning in the fall of 2012. So far, the oldest YES students are sophomores, so there's no graduation data yet. But the YES students here are all doing well -- even students who struggled in high school.

Luis Amaro says his big problem in high school was that he wasn't motivated to do the work. But his YES teachers pushed him hard.

"I remember, quite often, pulling Luis into my office, sitting him down and saying 'OK, what's going on? You gotta get it together," says Amaro's YES Prep counselor Monique Calderon.

"I can't tell you how many 'action plans' we created," says Calderon.

She says YES teachers and counselors knew that Amaro needed a small school where he could get the same kind of individualized support he got at YES Prep.

W&J is that kind of school. When Dean Newell walks across campus he is constantly calling out to students; he says he knows many of them by name. Newell regularly checks in on Amaro and the other YES alums; Amaro also goes to tutoring sessions and professors' office hours. He says he learned in high school that when you're struggling, you need to ask for help. But even students who aren't good at asking for help often get it at W&J; it's harder to fall through the cracks.

"I tell [the YES students] if they're looking for the collegiate equivalent of YES Prep, [where] people are going to know who they are, who are going to care for them, that's what we offer here," says Newell.

Newell thinks another reason W&J is a good fit for YES students is that W&J serves a more economically diverse student body than many other private colleges.

Most private, selective colleges have student bodies that are overwhelmingly drawn from the middle and upper classes. In fact, at the nation's most competitive colleges and universities, three-quarters of the students come from the highest-income families. Only 3 percent come from the lowest-income families.

But Washington and Jefferson College is different, says Al Newell.

"I refer to W&J as a 'ticket up' school," says Newell. "In a typical entering class, 25 to 30 percent of our students will be the first in their family to either attend college or to complete college."

W&J has a long history of serving the sons and daughters of Pennsylvania steelworkers and coal miners. In the middle of campus there is a bronze statue of a coal miner with an ax by his side and a book on his knee. It's a favorite place to stop and take photographs. A plaque on the statue reads: "The coal miners of this region toiled arduously in the hope of providing a better life for their children."

The Role of Social Class

Research shows that the gap in rates of college completion between students from high-income families and students from low-income families is growing. In 1980, students from the highest-income families were five times more likely to complete degrees; now they are nearly 10 times more likely.

Money is obviously one reason, and with college costs at record highs, money is an increasingly big factor. But as YES Prep is discovering, when students quit college, it's usually about more than just money. It is sometimes about social class, though.

Anh Nguyen grew up in a low-income family from Vietnam. She graduated from YES Prep in 2006 and went to George Washington University, one of the nation's most expensive schools. She says it was complete culture shock.

"I thought that I knew how to interact with people [who were] different from me because I grew up around Hispanics, African-Americans," she says. "And then whenever I did all these like college visits, that's what they showed us, it's just pretty much interacting with different races and nationalities and I'm like, easy. But I never took class into consideration, and that was where I got scared."

Nguyen made friends at George Washington but she never felt comfortable in an environment with so many students from wealthier families.

"I thought they were looking down on me. I was self-conscious," she says. "I was always looking over my shoulder, making sure I said the right thing. I didn't want to be laughed at."

Nguyen ended up leaving George Washington University after one semester. She eventually graduated from the University of Houston.

When low-income students go to college -- especially to the more elite colleges where YES is trying to send more of its graduates -- they often feel like they don't belong, according to YES Prep alumni program director Tenesha Villanueva. She says many students confront self-doubt as they get to know the other people on campus.

"Can I compare or measure up to them? Because they've had different types of schooling, they've had different types of exposure, they have more money, more this, more, more, more and I have less, less, less," says Villanueva. "They see themselves sometimes as 'less than' and they wonder, Do I have a place at the table? Like, should I be at the table?"

Norma Villanueva confronted these kinds of doubts when she went to college. Villanueva (no relation to Tenesha Villanueva) is a college counselor at one of the YES Prep schools. She grew up in south Texas and was one of only two people in her high school graduating class to go away to college. She went to DePauw University in Indiana and experienced the same kind of class shock that student Anh Nguyen described. It had an impact on Villanueva's ability to get help when she was struggling with classwork during her freshman year.

"I didn't know how to study, [and] I didn't really know how to ask for help," she says. But she didn't want anyone to know she was struggling because she feared it would confirm a stereotype that poor kids like her weren't up for the challenge of a college like DePauw.

"When I was a part of study groups, that was better," she says. "I think it was easier to ask my peers for help than asking a professor who I felt as though might be a bit judgmental and, based on how much they knew about my background, may think like, 'Yeah, no wonder this person doesn't get it. It's because they come from here.'"

Villanueva struggled through her freshman year and says she could have easily quit. In fact, she says some people back home were expecting her to give up.

"I was doing what people [in my community] don't do," she says. "The fact that I went away to college was celebrated, but also people were very critical. When I would return home for summer breaks, [friends would say], 'Hey, is everything OK? Thinking about coming back?'"

She got the sense they wanted her to come home. They were uncomfortable with the fact that she was doing something so out of the ordinary. Villanueva says this attitude inspired her to finish; she wanted to prove the doubters wrong.

The Role of Family

When you talk with the parents of YES Prep students, it's clear they want their children to achieve and have more opportunities than they have had. But some of them have mixed feelings about their children getting college degrees. A college degree is a ticket to the middle class, and some parents are anxious about what that transition might mean. They fear being left behind.

Counselor Norma Villanueva says when students encounter challenges or obstacles at college -- like a glitch with financial aid or feelings of homesickness -- some parents and other family members are quick to say, "Well if it's too hard, just come on home."

Parent Angelina Longoria says when her oldest son went away to Sam Houston State University in Huntsville, Texas, he was homesick. She and her sisters went to visit him during his first semester.

"And he announced that this was it. He couldn't do it anymore, he was tired of this," says Longoria. "And it was so funny because all of my sisters were ready to pack him up and bring him home and I said, 'Time out, time out.'"

She missed him too, but she wouldn't let him come home. Longoria says that since her son was born she's been hoping he would get a college degree -- in part because she tried to get one and never finished.

But for some parents -- perhaps especially those with no college experience themselves -- the costs and sacrifices and challenges of getting a degree may not seem worth it.

YES Prep graduate Angela Guerrero says her father wasn't convinced she needed a college degree.

"He's always been a laborer, so he thought that if you work hard, you will progress in your job," she says.

But when Guerrero graduated from YES in 2004 she really wanted to go to college. She got into Our Lady of the Lake University in San Antonio. She says she went against her father's wishes.

It was a struggle, though. Her parents called her every day and urged her to come home. They needed her help, they said. Her mom was having some medical problems and there were bills to pay. By the middle of her first semester at college, Guerrero says, her parents had made plans for her to come home and start selling real estate. She was reluctant to return to Houston, but she did.

Selling real estate was great for a while. But then the housing market went bust. Guerrero was stuck with few options. She got a job as an office clerk but couldn't move up without a degree. She even tried taking community college classes at night but says her boss told her she couldn't go to school. "Because it would interfere with my job performance," she says.

Guerrero quit community college in the middle of the semester. She lost her tuition but says she couldn't risk losing her job.

It took years of working dead-end jobs before Guerrero finally made a move that got her back on track for college. She took a job as a receptionist at a YES Prep school, and YES has a rule that if you're a YES alum and you don't have your degree yet, you must be going to college. So YES Prep alumni director Tenesha Villanueva sat down with Guerrero and helped her make a plan to return to college. Now Guerrero is a sophomore at the University of Houston.

Guerrero says her father has changed his mind about college. Watching her struggle in the job market without a degree convinced him that a college degree is necessary now. In fact, he's now urging his daughter to get a master's degree.

The Role of Expectation

From the beginning, YES Prep's goal has been to change the expectations for low-income students. Founder Chris Barbic felt that in the Houston elementary school where he taught, a big problem was that no one was expecting the kids to amount to much. He says expectations are powerful forces. You can't get more unless you expect more.

The expectation at YES has always been that students would go to college. Of course, everyone at YES assumed that meant graduating from college too, but that wasn't as explicit in the messages they were constantly sending to students. It was more about preparing for college, expecting to get there, seeing yourself as a college student.

But there's a big difference between getting to college and finishing, says YES Prep's Jennifer Hines. She thinks YES needs to do more to build an expectation of college completion. It's the kind of expectation she grew up with. It was just automatic.

"When I went to college it was for me," she says. "If I was struggling, I was just going to figure out how to get [through it] because this is just who I was."

But not all kids at YES have this attitude, Hines says. "I think sometimes, if kids are struggling, [they think], 'Well, maybe this isn't for me, then. Maybe, OK, well, I'm getting my first indications that I should just go back home.'"

Hines thinks some students from YES give up on college because they feel like they ought to give up.

It's like college was this thing that YES convinced them they could try, but once they get there they feel like they don't belong. There aren't many students on campus who come from similar backgrounds. When they struggle with schoolwork they conclude that they're not as smart or as well educated as other students. They're afraid to ask for help because they don't want to confirm stereotypes about low-income or minority students. Plus they're often getting conflicted messages from friends and family: Get the degree -- but not if it costs too much, not if it's too hard, not if it's going to take you away from where you came from.

Hines thinks low-income and first-generation college students across the country are likely confronting these same kinds of emotions when they go to college.

And with the dropout rate so high among these students, there's a risk that going to college and dropping out has become an expectation among some students.

Proving You Can Do It

Like YES counselor Norma Villanueva, YES alumna Yesenia Soto confronted a lot of doubt when she became the first one in her family to try college. She says some family members were expecting her to fail.

"It had never happened in our family, so they just thought, 'Oh, you can't do it,'" says Soto.

At times, she thought her family might be right. Soto graduated from YES in 2005 and went to the University of Houston. At one point she failed a class, and she had all kinds of negative things going through her head.

"I thought that I wasn't smart enough or that I couldn't do it," she says.

And she got scared. "What if I get kicked out? What's the next step? What am I going to do?"

Her hold on college felt tenuous. Unlike students from college-educated families, graduation was not an expectation in Soto's family. In fact, she has a cousin who went to college after she did and ended up quitting. She has many friends who had started college and quit, too. That seemed like the norm.

But Soto kept going. While she was in school she worked as a receptionist at YES Prep, and during that time YES made the rule that if you're working at YES and you don't have a degree yet, you must keep going to college. Soto says that rule was a blessing because it forced her to stay in school. She says if it weren't for YES, she probably would have quit college. The people at YES were the ones "looking after me, asking me all the time, 'How's school going, how are your grades?'"

Soto graduated from the University of Houston in December 2011. She believes the fact that she graduated will increase the chances that her younger brothers and her cousins can go to college and get degrees too.

The Role of Grit

Students like Yesenia Soto who persist through challenges in college have become a particular focus for YES Prep in the past year. Teachers and administrators want to know why someone like Soto finishes college when another student who faces the same kinds of challenges decides to give up.

YES has become convinced that there's a personal quality called "grit" that may make the difference.

Psychology professor Angela Duckworth studies grit. She defines it as "perseverance and passion for long-term goals."

"Grit is sticking with things over the very long term until you master them," Duckworth says. She also uses words like tenacity, persistence and pluck. She believes grit may be a significant trait for getting through college, especially when there are a lot of challenges.

Grit may not be necessary for students whose families have always expected them to get degrees and who have resources -- financial and otherwise -- to support their children through college.

"I think many of us, because of the frictionless paths that are laid in front of us by having come from where we come from, need less grit than others," Duckworth says.

In fact, Duckworth's previous research shows that people who complete bachelor's degrees actually have less grit than people who complete associate's degrees. Duckworth believes that's because the people who try to get associate's degrees tend to face more challenges than the majority of people who attempt a bachelor's. Nearly 80 percent of students who go to community colleges are from low-income families. Many of them are the first generation in their family to go to college.

Now Duckworth is studying students at YES Prep to try to understand whether grit is something that helps students make it through college. If it is, the goal is to try to teach students to be grittier about getting through college. It's not clear yet whether this can be done, or how, but teachers and administrators at YES are eager to find out.

YES alumni director Chad Spurgeon is convinced from his experience working with students that some of them are just more willing to "grit it out" than others.

But he does worry that the focus on grit could be a double-edged sword.

"The largest issue, I think, is poverty, it's inequality," he says. "We don't want to downplay the significance of these kids being born into situations that are unjust and then if they don't make it accuse them of just not being gritty."

He says it would be wrong to dismiss the college completion problem among first-generation, low-income students as just personal failure. Spurgeon says there's much more going on, and many things could be done to better support low-income students and help them succeed. He believes schools like YES Prep have a responsibility to do everything they can to make sure students graduate from college. That's not traditionally been the responsibility of high schools, but he thinks it should be. YES founder Chris Barbic agrees. And he thinks colleges need to be doing more too.

"Colleges have to step up their game in terms of the kind of support they're providing to kids, and that's just not happening," he says.

Barbic recently left YES to become superintendent of a new district in Tennessee made up of the lowest-performing schools in the state. Almost all of the students are low income. The goal is to get those students to college graduation, too. Barbic says he's taking everything he's learned at YES to try to make that happen. He's particularly eager to learn more about the results of Duckworth's research on YES students and grit. He says first-generation college students need every advantage they can get.