When the Great Recession hit in 2008, doors stopped opening for Gary Horsfall. This was after three decades Horsfall spent in business, as a company president, general manager, comptroller and supply-chain specialist. The reason: Horsfall, like millions of Americans, never finished college. When he was between jobs and looking for work, Horsfall discovered academic credentials matter more in a tight economy; less impressive applications get an express trip to the recycling bin.

"I know there's a lot of resumes that I send out that people don't look at because they check the degree box and I'm in the round file right away," Horsfall says. "They never get around to looking at the background."

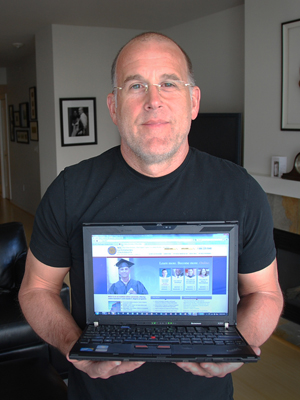

So Horsfall, 53, enrolled in a relatively new university where he could get a BA in business management based on what he knows, not how many semesters he's racked up in the classroom. If all goes on schedule, Horsfall will complete his undergraduate work at Western Governor's University (WGU) in less than 16 months. And it will cost him a fraction of what he'd spend at a local college or university.

WGU is like no other American university. It is designed to meet the needs of working adults who want to further their education but don't have the time to attend a conventional community college or university. Some 34,000 students from all 50 states are enrolled at WGU. It is a completely online, nonprofit school created in 1995 by a group of western state governors (and the governor of Guam) who wanted to meet the growing demand for higher education at a time of limited public funding. The emerging world of internet education offered an alternative to building expensive new campuses.

The governors also backed the unusual idea of tossing out attendance requirements in favor of a program based entirely on measuring a student's mastery of his or her chosen field.

"We don't require that you sit through classes," says WGU President Bob Mendenhall. Most other colleges and universities grant degrees on the basis of course credit hours; at WGU, each student learns at an individual pace. If a student knows the material, she can take tests and pass a course without ever looking at class readings or exercises.

"What the university does is say, it doesn't matter where you learn, it doesn't matter from whom you learn. All that matters is that you learn," says Kevin Kinser, an education professor at the State University of New York at Albany. Kinser studies online education and has followed WGU closely from its inception.

"What the university certifies is that you have competency in the subject matter according to the criteria they've developed," Kinser says.

WGU is fully accredited, meaning its programs have been reviewed and approved by the quality-control system that oversees colleges and universities. WGU students are required to enroll full-time, but the courses are self-paced. The flat-rate tuition is about $6,000 per year. There's no limit on how many credits a student can earn in a given term. So, for example, a mid-career professional with deep experience in computer technology may whip through a bachelor's in information technology much faster than a neophyte. WGU officials say the average student graduates with a bachelor's degree in 2.5 years, compared to four years or more at a conventional school. That means a degree at WGU runs about $15,000 -- less than half what it would cost at a public, bricks-and-mortar college or university.

Mentors not Professors

WGU offers what it calls workforce degrees. Its programs are limited to business, information technology, health care professions and teaching. College officials developed the criteria for what students should demonstrate they know in a given field by consulting, in part, with business and industry groups. Many of the WGU faculty have advanced degrees in their fields, but there are no professors.

"In a traditional university, you have a faculty member who designs a curriculum, teaches that curriculum, evaluates students on how well they've learned that curriculum and then assigns a grade. It's all done by one person," Kevin Kinser says.

Instead, WGU employs student mentors, course mentors and a separate cadre of evaluators whose only job is to grade performance. WGU creates virtually none of its own curriculum. It buys or licenses existing online course materials from for-profit education companies and other public institutions. All of this is meant to keep costs down by making the parts interchangeable and easily updated.

"At WGU we're really using the technology to do the teaching," Mendenhall says. "Whether that technology is serving 10 students or 100 students or 100,000 students, the costs are essentially the same."

WGU students get assigned a personal mentor for the entire course of their education. First-term students are required to talk to their mentor at least once a week. WGU is based in Salt Lake City, but its faculty are scattered across the map. Connie Ozmer keeps track of her 88 student advisees from a desk in the bedroom of her townhouse in Puyallup, Wash. Ozmer is a 42-year-old mother of two with a background in information technology. She earned her master's degree in education from the University of Phoenix.

"The biggest thing in an online school is accountability," Ozmer says. "I help students set goals, put home life in perspective for the week ahead and help them progress through the program."

WGU students are almost all working adults who have attended college in the past. Ozmer says her main task is to help them balance family and work demands. "They get caught up in their day-to-day lives and school is always the first thing to go," Ozmer says with a laugh as she slips on her telephone headset and logs in to the WGU advising system on her laptop.

Punching in a phone number, Ozmer connects with Brandi, a business undergrad in Georgia. Brandi updates Ozmer on her baby and her teenager and her husband and an upcoming appointment for surgery on her thumb. Then Brandi concedes she's having trouble with a current chapter of the online reading on organizational management. "I don't want to manage people," Brandi says, "so reading this stuff is worse than reading instructions on how to set up my stereo."

As students move through each section of a course, they typically take a preliminary test to measure their existing knowledge. Those who are ready can go straight to the final test. Others get a picture of what they need to learn or review in order to pass.

"Students tend to think, I have all this experience, I don't need your resources. They go in and take a test. Then the lesson is learned and they know they have to take this course seriously," Ozmer says.

Cheating is a major concern at most colleges and universities. It would seem even more vexing at a school where no one ever meets face-to-face. WGU uses several solutions. One is requiring students to go to independent, proctored testing centers for certain tests and certificates. The other solution is a webcam.

Gail Hopkins is a payroll administrator at a Seattle baking products company. A single mom in her 50s, Hopkins is studying for a bachelor's in business management at WGU. Hopkins takes her tests at home in her bedroom. WGU sent her a webcam that keeps watch on her. No one else is allowed in the room when Hopkins is testing. But she does let her two protective dogs, Jackson and Daisy, sleep on the bed.

"If I closed them out, they'd be outside scratching at the door," Hopkins says with a grin.

When WGU students need help with a specific class, they contact a course mentor (different from their personal mentor) who guides them through the readings, exercises and other materials. The course mentors have advanced degrees in their fields and have often taught at other colleges. There are also online forums where WGU students can chat about specific classes or share the general experience of online college life.

WGU's enrollment has been growing at about 34 percent a year for the past five years. A majority of its students receive some form of federal financial aid. WGU says its graduation rate is 40 percent. Comparisons with other institutions are difficult because of how student data are collected. The national average completion rate is 58 percent, according to the US Department of Education. A survey by WGU found more than half of its graduates said they got a new job, a promotion or a raise because of getting their degree.

WGU in Washington State

In 2011, the Washington state legislature created WGU Washington as a recognized state university. Indiana and Texas also have WGU branches. From a small suite of offices in a downtown Seattle office building, WGU Washington chancellor Jean Floten is striving to grow enrollment from 3,300 to 10,000 students five years from now.

"Washington has morphed into an extremely advanced technological economy. Because of that, knowledge and skills are needed." Floten says. The state is home to tech powerhouses like Amazon and Microsoft (Microsoft founder Bill Gates' foundation granted WGU $4.5 million to support its expansion in Washington, Texas and Indiana) . A recent study ranked Washington sixth in terms of the intensity of skills that will be required for future jobs. "Yet our production of bachelor's degrees is about forty-eighth in the country," Floten adds.

A particular bottleneck faces students in Washington trying to transfer from a two-year community college to a four-year institution where bachelor's degrees are offered, according to Joni Finney, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania's Graduate School of Education. Washington simply does not have enough four-year programs to meet demand. "Like a lot of other states, Washington needs more people to earn a bachelor's degree. This is a problem that the legislature and the governor have refused to solve," Finney says, adding that WGU is only a partial solution.

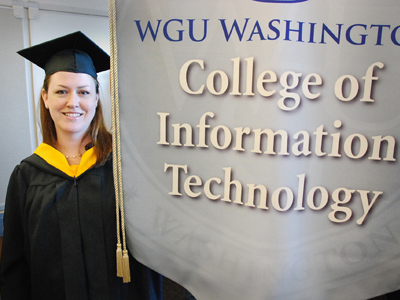

WGU Washington held its first graduation ceremony in April 2012. Most of the 53 participating grads had signed on with WGU before the Washington branch opened, but took the opportunity to pull on a cap and gown for the commencement ritual, which was held at a waterside convention center in downtown Seattle.

Graduation marked the first time 26-year-old Erin Gann had ever met other WGU students or faculty face-to-face. A string quartet played "Pomp and Circumstance" as happy graduates made their way to the stage. Afterward, Gann met up with her husband, their one-year-old son, her parents and other relatives. "I feel wonderful," Gann said as she posed for snapshots. "I worked so long and hard. I'm proud of myself."

Gann had started at WGU three years earlier. She was working full-time in a Tacoma public school office and helping care for a stepdaughter, so she needed the flexibility of an online school. She had the baby along the way. Gann did her schoolwork whenever she found a scrap of time.

"I would study in the car while my stepdaughter was doing soccer, I studied in the storage room at work during lunch. If I had 15 minutes I studied," Gann says with a laugh. "I would do it late at night when the kids were in bed or really early in the morning." Gann earned a master's degree in elementary education from WGU and teaches seventh-grade humanities at a public school in Tacoma.

"I wouldn't be teaching right now if it weren't for WGU," Gann says.

A Game Changer?

WGU Washington may be more of a competitive threat to for-profit online schools than the state's overburdened public colleges and universities. Most WGU students are working adults. Many have families. These so-called nontraditional students have driven the boom in the for-profit sector. But at an average of $15,000, the cost of a bachelor's degree from WGU is less than a quarter the cost at a for-profit school, according to a recent U.S. Senate report.

Because of their schedules, many WGU students would never be able to attend a bricks-and-mortar Washington state school. Still, the organization representing faculty at Washington's regional universities opposed the creation of WGU Washington.

"The model for making it cheaper is cutting out the faculty," says Bill Lyne, president of United Faculty of Washington State and an English professor at Western Washington University. "What we are creating is a class system where people who can pay for it will continue to get the education provided by professors at major universities. And everyone else is going to be teaching themselves online."

Lyne also decries the dwindling investment many states -- including Washington -- are making in higher education. He views WGU as a dodge -- a way for the state to partially solve its college capacity problem without spending money.

"I'm not worried about losing my job because of Western Governors University," Lyne says. "I'm worried that this country is losing the giant engine that drove democratization and middle class mobility and the industrial capacity of the United States in the twentieth century -- big, public, state universities. Where regular people could pay nominal fees and go get the same education that rich people could get at Princeton and Harvard."

WGU Washington chancellor Jean Floten is puzzled by the criticism. She argues that WGU is simply a new model for reaching students that would otherwise go unserved. "I think the classroom experience is great. But for an adult trying to get an alternative education, this is a solid, creative way," Floten says.

Has WGU become the game-changing university envisioned by the group of governors that met back in the mid-90s? Not yet, says online education researcher Kevin Kinser. "It was a little bit ahead of its time," he says. "The technology had to catch up with the concept." In some respects, the explosion of massively open free courses offered by big-name schools like Stanford and Harvard is the next wave of change, he says.

"WGU was founded on the idea that where learning occurred was irrelevant," Kinser says. "To the extent that there's more places for students to gain access to high-quality materials, that feeds into the WGU model."

As he dashes towards completion of his B.A., Seattle businessman Gary Horsfall does contract business consulting to pay bills. He lives in a stylish condo near Seattle's waterfront. He's getting by, but he wants the kind of solid, long-term job at a major company that, in today's economy, requires a college degree. He plans to get an MBA from WGU as well. Horsfall says his professional life might have been easier if he hadn't dropped out of college. "It hasn't stopped me from being very successful," Horsfall says. "But I feel like I've probably had to work harder than other people to get to a similar place."