First-generation college students are twice as likely to quit college as students whose parents have bachelor's degrees. Meet four students whose stories illustrate why it's a challenge to be the first in your family to go to college.

"In my family it's rare to even get a high school degree," says Yesenia Soto. "So for someone to get a college degree… it's a big deal."

When Soto was young, she didn't expect to go to college. It's not something people in her family talked about. Her parents were born in Mexico. She says college wasn't an option for them. They had to work.

It wasn't until Soto started going to the YES Prep Southeast charter school in 6th grade that college began to seem like a possibility. Even then it seemed pretty vague and far away.

"I live in Houston but I had never visited the University of Houston," she says. She'd never been on any college campus.

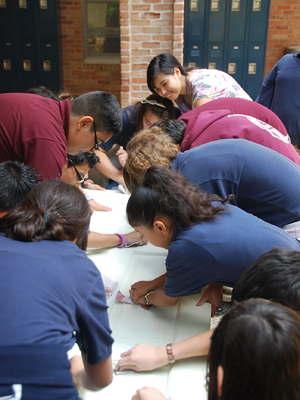

But the constant message from YES Prep teachers and staff was: Picture yourself at college. Teachers wore college T-shirts on Fridays and displayed college pennants in their classrooms.

When she was in eighth grade, Soto's class went on a college tour to Washington, D.C. That's when she began to be convinced. "Just looking at the students," she says. "I just saw myself in that position."

At first she had her heart set on college somewhere out of state, but she realized she would miss her family too much. Soto has a big extended family and they all get together on Sundays at her grandmother's house in Houston.

Plus, she wanted to help her mom. Her father had had some legal problems and went back to Mexico when Soto was in middle school. Soto was helping to care for her younger brothers and she wanted to start helping her mom with the bills. As a high school graduate, Soto felt it was her responsibility to work for the family. And she had to work to pay tuition.

"I knew my mom couldn't pay for it," says Soto.

Soto went to the University of Houston. The University has what it calls a "Main Campus" that is more selective and prestigious than the "Downtown" campus, which offers a lot of classes at night and is geared more toward the needs of commuter students who go to school part time.

Soto started at the Main Campus, where there are many signs of "traditional" college life, like dorms and a football team. She didn't have time to participate in much of that on-campus activity because she was working part time and commuting from home. And she soon realized that working part time wasn't enough to cover tuition and help with the household bills, so she increased her hours at work and transferred to the Downtown campus, where she could take classes at night.

Working full time and going to school full time was a big challenge. At one point she failed a class and her college dream felt like it was slipping away.

"What if I get kicked out?" she thought. "What's the next step? What am I going to do?"

She couldn't get these anxious thoughts of her head. The failure felt like a sign that maybe she wasn't meant to be in college.

"I thought that I wasn't smart enough or that I couldn't do it," she says.

A lot of college students hit this kind of moment. They struggle and it causes them to question their skills and abilities. But when it happened to Soto, she also had the voices of family members in the back of her head. She says some of them were expecting her to fail because people in her family didn't get college degrees.

"It had never happened in our family, so they just thought, Oh, you can't do it," she says. "They just assumed… because no one else had done it before."

Soto was also facing another fear: She didn't want to go to her professors for help.

"I'm really shy, so I never wanted to go and ask," she says.

The only people she felt comfortable going to for help were her teachers at YES Prep.

"The teachers at YES, I've known them since sixth grade," she says. "They know me on a personal level. They know the struggles that I've been through and my family problems. And they're always willing to help."

Soto's job was working as a receptionist at a YES school, so it was easy to get in touch with her YES teachers. She says her math teachers were the ones she needed most.

YES helped her in another way too. In 2008 the school put a rule in place that if you're a YES Prep graduate working at YES and you haven't finished your bachelor's degree yet, you must be going to school -- full-time. Soto says that rule more than anything else got her through college.

"If it wasn't for them, I probably would've stopped because they're the ones looking after me, asking me all the time, 'How's school going? How are you doing in school? How are your grades?'"

Soto graduated from the University of Houston-Downtown in December of 2011.

"I just feel relief," she says. "Because a lot of people always said [I] couldn't do it. And I did."

Soto works as an operations coordinator at YES Prep and is the varsity girls' basketball coach at one of the YES schools. She's not sure what career she wants.

"Right now I'm just enjoying my time out of school!" she says.

And she's focused on helping her younger brothers and her cousins eventually get through college.

"They're all looking at me." She says her aunts and uncles often point to her at family gatherings and say, "Well, if she did it, then my son or daughter can do it."

"I think that we're changing our family's future," says Soto.

When it came to college, Angela Guerrero's parents disagreed.

Her mother wanted her to go. She was born in Mexico but went to high school in the United States. "She kind of knew that what you needed in the workforce is to have an education past high school," says Guerrero.

But Guerrero's father wasn't convinced about college. "He's always been a laborer, so he thought that working hard is how you [get ahead]. Like if you work hard, you will progress in your job," she says.

Guerrero, who is an only child, sided with her mother; she wanted to go to college, and that's what YES Prep was preparing her for.

When she got accepted to our Lady of the Lake University in San Antonio, she was excited. Her dad wasn't. He didn't want her to go.

"But, um, I kind of was… not rebellious, but I felt like that's my next step," she says, giggling at the memory of being just a bit more rebellious than she'd ever been before. "I needed to be more independent, so -- against his wishes, of course -- I left."

She loved college, but every day her parents called her.

"They would just hint at, 'We really miss you and we really need you to come back,'" she says.

Guerrero's mom was having some health problems. She'd stopped working and there were medical bills to pay. Her father said Guerrero needed to come home and work.

Guerrero says her mom is "traditional. Like, whatever your dad says is the right way." Her mom told her: "There will be another time for you to go back."

Guerrero came home. But the time to return to college never seemed to come.

She started selling real estate. That was when the housing market was booming. She says she made enough money to support herself and her parents.

When the housing market crashed, things got tight. Guerrero needed to find work as fast as possible. She got a job as a receptionist at an architecture firm. "I put in very long hours and I handled everything that there was, like all of the financial documentation," she says. "I was the 'go-to' person."

But after three years on the job she was still stuck in the same position and making only a dollar more an hour than when she'd started.

"I wasn't being taken seriously," she says. Other people came in with no experience and moved up quickly, and she knew it was because they had college degrees and she didn't.

"I felt like it was unfair," she says, "but then again, basically it was my fault," since she hadn't found a way back to college.

So she took the plunge and signed up for night classes at Houston Community College. About halfway through the semester, she says, her boss at the architecture firm found out she was going to school. He told her she had to quit college "because it would interfere with my job performance," she says.

"I felt like they were trying to oppress me!" she says. "It was just horrible."

But she did what he said and left school so she wouldn't lose her job.

It took Guerrero several more years to find a way to make college work. As it turned out, the answer was YES Prep.

In 2011 she got a job as a receptionist at a YES Prep school, and YES has a rule that if you're a YES graduate and you don't have your degree yet, you must be going to college. YES Prep's co-director of alumni programs, Tenesha Villanueva, helped Guerrero make a college plan. They met at a coffee shop.

"I brought all my transcripts," Guerrero says. She hated looking at the one from Houston Community College that said "withdrew" across the page.

Villanueva brought her laptop.

"We were just there having fun, looking up things that I was interested in, programs at different universities that I thought I'd be interested in applying to," Guerrero says with a laugh. "It was a fun, relaxing time to set up my future."

Guerrero is now a student at the University of Houston-Downtown. She's thinking about majoring in social work. She thinks she can finish by 2015, eleven years after she graduated from high school.

"I don't foresee anything getting in my way," she says.

The people she works with at YES encourage her. "I really do want to finish," she says, especially because "everyone around me [at work] is a college graduate and I don't want to be left behind."

Guerrero says even her father is now convinced that she needs a degree. In fact, he wants her to get a master's degree. Watching her struggle to move up made him realize that the "new" American dream requires not just a strong work ethic but a college education, too.

Paul Longoria had a college plan. He was going to Sam Houston State University in Huntsville, Texas, to study criminal justice. His older brother was a junior there.

But about a week before YES Prep's big "Senior Signing Day," when graduating seniors declare what college they're going to attend, Longoria got a rejection letter from Sam Houston State.

"I remember being devastated," he says. "I didn't have a back-up plan at all."

He had also been accepted at the University of Houston. That's where his YES Prep counselors wanted him to go. YES's goal is to have students attend four-year schools.

But he didn't want to go to the University of Houston. He thought it would be better to go to a community college for a year and then try to transfer to Sam Houston. "It was not a very favored decision," he says, describing the reaction of people at YES Prep.

According to the data YES has on how its students do at various kinds of colleges, students who go to community colleges have the hardest time graduating. Only a handful of YES students start at community colleges, but about 13 percent who start at a four-year school end up transferring to a community college. Less than 10 percent of those who transfer to community colleges earn an associate's degree, according to YES Prep data. Less than 5 percent end up earning a bachelor's.

Paul Longoria had a vague idea of the odds, and he knew he could beat them.

Longoria went to San Jacinto Community College in Houston. "I took my basics -- basic English, basic math, basic reading," he says. He had gotten a "transfer sheet" from Sam Houston State and it looked like he could get credit there for all of his community college classes.

He succeeded in transferring to Sam Houston after a year in community college. But a lot of his credits wouldn't transfer. That was a big blow.

"You almost feel cheated," he says. "I put in the time, I put in the effort, I surely put in the money. And you're telling me that it didn't matter."

He says "about every second thought that went through my head" was to give up on Sam Houston and stay in community college. "Just get an associate's degree. If you're lucky, you can get a job," he remembers thinking.

But saying that out loud didn't sound right. "Being that I put so much time into my education at YES, I felt like it would have been a waste for me, my family, and almost embarrassing just to choose the easy way out," he says.

Longoria's parents don't have college degrees, but they've always wanted their sons to get them. Longoria's mother, Angelina Longoria, tried a junior college close to home.

"I was afraid," she says. Her parents didn't go to college, and Longoria felt it was too far to travel -- literally and figuratively -- to go to a university and try for a four-year degree. "I was comfortable where I was," she says. She never finished at the junior college.

But since her sons were born, Longoria has dreamed about their getting degrees. She says as they neared high school graduation she started to feel scared, not because she didn't want them to go to college, but because she wanted it "so bad." It was something that had slipped away from her, and she wasn't going to let that happen to her boys.

Apparently she kept her emotions to herself, because Paul Longoria says his mom was calm and supportive as he struggled with the transfer process. He didn't bother her with a lot of the details, though. It was his older brother he relied on most.

"Matthew was my academic advisor, financial advisor," Longoria says. "He was really someone I looked up to because he had already been through the whole process. He already knew what to expect, and when I needed help, he was right there."

At Sam Houston, Longoria had to take a number of courses over again because the community college credits wouldn't transfer. It cost him time and money, and taught him a valuable lesson that lots of college students learn the hard way: Talk to an advisor. If he had, he says, he might have been able to avoid taking some classes twice, though schools routinely reject credits from other schools during the transfer process.

At first, Sam Houston was everything Longoria had hoped it would be. He was living on campus, majoring in criminal justice; it was his college dream. "I was on my own, I was going to class, I was going to the rec center everyday," he says. "It felt great."

But two years into his coursework at Sam Houston, Longoria says he woke up one morning and "had what you might call an epiphany." He realized he didn't really like the criminal justice program; he had been thinking about becoming a police officer or pursuing some other law enforcement career, and quite suddenly it clicked that that wasn't what he wanted to do.

He wanted to help people and says criminal justice "didn't feel like helping people."

He started thinking about himself, what he liked, what he really wanted to do. He talked to his advisor, who introduced him to the field of kinesiology, the study of human movement. Longoria has always been into working out. He had tried out for the powerlifting team at Sam Houston but decided against joining because the fees were high and he was required to buy a special suit that cost $85. He couldn't afford it.

Longoria decided to change his major to kinesiology, and he learned that one of the best programs was at the University of Houston. So he transferred again and moved back home. That meant starting over with introductory classes once more. The move set him back about a year in school. He wondered whether it was worth it. Quitting crossed his mind. But again, the thought of disappointing his parents, his brother -- and disappointing YES Prep -- made him keep going.

He remembered one of the things people at YES used to say to him: "Anything worth doing is worth doing right." It's actually a phrase posted on the walls at YES schools.

Longoria wanted to be able to say that about college -- and about how he prepared for his future.

"I could have been a criminal justice major, settled, but I wouldn't have been happy," he says. "That's no way to live life, in my opinion."

Longoria expects to finish his bachelor's degree in kinesiology by December of 2013. He assumes graduate school will be next.

He thinks if he hadn't gone to YES Prep, he probably would have gone to college, given how focused his parents were on it. But he thinks he would have stayed at community college, maybe gotten an associate's degree. "I wouldn't have known what it was to want more," he says. "I would've been very happy with doing the bare minimum. But luckily I went to YES, where the bare minimum was never accepted."

Anh Nguyen's parents didn't go to college, but she always knew she would.

Her parents are immigrants from Vietnam. "They didn't know much [about college]," Nguyen says, "but they knew they wanted us to [go]."

Nguyen's older sister went to a community college in Houston. Nguyen remembers going to campus with her, but it wasn't like the colleges she saw on TV shows. She wanted to go away and live on campus like the kids on television.

She did. After graduating from YES Prep Southeast in 2006 she went to George Washington University in Washington, D.C.

"I got there and it was culture shock," she says.

George Washington is one of the most expensive universities in the United States. It's known for attracting lots of wealthy students. Nguyen wasn't prepared for the class differences.

"I came from lower-middle-class Houston," she says. "And I dormed with a girl from Taiwan who's traveled and done all these crazy conference things. And then my other roommate was from California and she's traveled the world."

Nguyen felt inadequate and inexperienced by comparison.

"I thought I knew how to interact with people [who were] different from me because I grew up around Hispanics, African-Americans, so I was like, I'm good with that," she says. "And then whenever I did all these college visits, that's what they showed us, it's just pretty much interacting with different races and nationalities and I'm like, easy. But I never took class into consideration, and that was where I got scared."

She says it was intimidating to be around people who had so much more money than she did. They knew more about politics and current events. They seemed to know more about everything.

"I was self-conscious," she says. "I was always looking over my shoulder, making sure I said the right thing. I didn't want to be laughed at."

She says the isolation she felt made her long for home. She called Donald Kamentz, her college counselor from YES Prep.

"I don't think I can do this," she told him. Nguyen didn't want to talk to him about the social class issues. She told him she just needed to be closer to Houston.

So after one semester at GW she transferred to Tulane University in New Orleans. "I want to be down south," she thought. "I think maybe the culture down there will make me feel more at home."

But at Tulane -- also an expensive university that attracts many students from wealthy families -- Nguyen says she felt just as isolated, if not more so. She arrived on campus in January, students had already made friends, and she felt terribly lonely. She made the six- hour drive home to Houston every other weekend.

At the end of the semester she decided she'd made a terrible mistake. She called Mr. Kamentz again and told him she wanted to go back to George Washington. She did.

"I loved it," she says. "I was there for a year and a half, and it was great." She realized she'd made good friends during that first semester and when she went back they were all glad to see her. The class differences didn't seem so extreme anymore; she was finding a way to fit in.

Then her parents announced they were getting divorced.

Nguyen called Mr. Kamentz again and said, "I have to go home." He tried to convince her to stay. "He's like, 'You're almost done! Why are you doing this?'"

But she says she was depressed and couldn't focus. She was especially worried about her dad. So she went back to Houston and moved in with him.

College was much harder once she got home. She got a job because she didn't want her father to have to pay for any of her living expenses. She enrolled at the University of Houston. Even though it's a state school, it cost her much more than George Washington, where she'd had a great financial aid package.

"If I had stayed at GW I would have left with about $3,600 in debt," she says. Instead, she says she has about $30,000 in student debt. She used some of her student loan money to pay for living expenses. Also, she had to pay for extra classes at the University of Houston because the school would not accept some her GW credits.

"It was frustrating," she says.

The idea of quitting crossed her mind. She could have explained it to her parents. "Get a job that pays decent and they would understand," she says.

But the people she couldn't explain quitting to were her teachers and counselors from YES Prep. "Not finishing would have been disappointing them," she says. "And I couldn't do that."

Plus, she wants to be a teacher. For that, she knew, she had to get a degree. She finished her bachelor's at the University of Houston in December of 2011.

"Graduate school is in my future," she says. She's thinking about a degree in special education, and her hope is to be a teacher at a YES school someday. For now she has a temporary job at YES, helping to set up the library at a new school and teaching an art class to sixth-graders. She and her husband are planning to live in Vietnam for two years. She wants to see more of the world, and then come home and figure out a way to get to graduate school.

She says if she could go back and tell her 19-year-old self anything, it would be, "Put yourself first." She thinks her father would have understood if she'd said she was staying at George Washington to finish her degree. After all, that's what he'd always said he wanted.