SEPTEMBER 2013

The General Educational Development test (GED) is a second chance for millions of people who didn't finish high school. Each year, more than 700,000 people take the GED test. People who pass it are supposed to possess a level of education and skills equivalent to those of a high school graduate. Most test-takers hope the GED will lead to a better job or more education.

But critics say the GED encourages some students to drop out of school. And research shows the credential is of little value to most people who get one.

Chad Phelps dreams of turning the thing he adores into a job that pays. Phelps is 26 and lives with his grandparents in the countryside near Cedar Rapids, Iowa. He's spent the last decade drifting from one relative's house to another, composing hip hop music on his computer and designing album covers for musician friends while working at fast food joints to earn a living. He wants to trade the drudge jobs for a gig in a recording studio.

Chad Phelps, 26, has been composing music since he dropped out of high school in ninth grade. Now that he has his GED, he wants to go to college and become an audio engineer. May 2013. Photo: Laurie Stern.

"Since I was 15 years old, I loved doing music," Phelps says. "I could sit here and spend ten to 16 hours straight, every day. It's something I love doing."

It doesn't necessarily take a college diploma to make it in the entertainment industry, though Phelps thinks it would help. He wants to study audio engineering at the local community college. But he dropped out of school in ninth grade.

"He had a lot of troubles growing up in school," says his mom, Cheryl Phelps. "Fighting a lot. He just said I'm not doing it anymore."

Phelps says he was just being young and dumb when he quit school. "At that age, I didn't think it was really that important," he says.

Ten years working at Pizza Hut, Taco Bell and similar jobs changed his mind. In the summer of 2012, Phelps began preparing to take the GED test. If he passes, he'll get a high school credential. There are an estimated 39 million American adults who don't have a high school diploma. In 2012 more than 700,000 of them took the GED test. Like Phelps, most of them hope that a GED will help them get a better job or more education.

On this map, the darker the color of the state, the higher the percentage of adults without a high school credential. Hover over the states to see the number of test-takers and passers in each.

State policies can have a big impact on the number of people who pass the GED. In New York, for example, anyone 16 or older can take the GED for free. The pass rate is 53 percent. In Iowa, to be eligible to take the test you must demonstrate you have a good chance of passing by getting minimum scores on a GED practice test or other standardized test first. The pass rate is 62 percent.

Sources: U.S. Department of Commerce, Census Bureau, Current Population Survey (CPS), October 2012 (data prepared September 2013); 2012 Annual Statistical Report, GED Testing Service.

Notes: Adults are defined as 16-year-olds and older not enrolled in high school. Data contain sampling errors.

There are five sections of the GED test: reading, social studies, science, writing and math. Chad Phelps took the test in the spring of 2013 at Kirkwood Community College's high school completion center in Cedar Rapids.

He says the first three sections of the test were easy for him -- he didn't really study in advance. But writing and math were a different story. He took prep classes for about 12 weeks getting ready for those parts of the test. He had to take some parts more than once to pass. But eventually he did.

"It was pretty smooth," Phelps says.

The whole GED test takes about seven hours. The questions are multiple choice. There is also a short essay to write.

12%

of high school credentials are GEDs. [source]

Phelps' experience with the subject tests was fairly typical, according to Marcel Kielkucki, director of Kirkwood's high school completion programs. To pass, you don't have to memorize facts about U.S. history or cellular biology or the planets in the solar system. If you understand the basic concepts of a subject, the test questions provide all the clues you need.

"So, if you're a good reader, you can read the content for understanding in the social studies and science tests," Kielkucki says. "You'll be able to pick up the context clues from the material most likely and pass." He says test-takers generally find the math and writing tests more challenging.

The GED was introduced in 1942. The score required to pass has been raised over the years and there have some updates to the content of the test, but the fundamental principle remains largely the same. It is supposed to determine whether test-takers have the skills equivalent to those of a graduating high school senior. But from the outset, critics said the test was too easy. It was based on a test that a majority of students were able to pass at the beginning of high school, not the end. Research suggests the current version of the GED tests knowledge at about a ninth- or 10th-grade level.

"I passed it with flying colors," Josh Woodward says proudly.

Woodward is 19. He dropped out his junior year. He was struggling academically and socially at his school in Cedar Rapids. A sympathetic teacher suggested he give up on high school and try the GED instead.

After getting his GED, Josh Woodward took a paid internship at Midwest Metal Products in Cedar Rapids, Iowa. He also enrolled in a machine class at Kirkwood Community College. March 2013. Photo: Stephen Smith.

Armed with his GED certificate, Woodward enrolled in a course on precision machining at Kirkwood Community College. He also got a paid internship at Midwest Metal Products, a machine shop that manufactures components for the defense industry and other clients. Midwest Metal Products offers a scholarship that could help Woodward earn a two-year degree in advanced manufacturing. "I'm trying to say, 'Hey, I'm your guy -- give me that scholarship,'" Woodward says. "Being able to have a degree is going to be huge. It's going to be phenomenal."

It's a challenging goal. According to research, the odds are against him. Fewer than 10 percent of the people who get a GED complete a two-year degree, and even fewer get a four-year diploma.

Woodward is in community college classes four hours each afternoon. Then he heads to Midwest Metal Products, where he does entry-level work from 6 to 11:30 p.m. "I get home, fall on my face asleep, and then I get up the next morning to go to class again," Woodward says. "I'm a very busy person."

If Woodward gets a two-year degree in advanced manufacturing and works long enough, he can earn up to $28 an hour, according to Midwest Metal Products' Human Resources Manager Yvonne Hoth.

She says Woodward is younger than most entry-level workers she hires, but she liked what she calls his "can-do" spirit. Her philosophy is that just about anyone can be taught how to run the lathes and mills in a modern machine shop. "What you can't train them to do is show up on time, have the right attitude, get along with people, be engaged," Hoth says.

Josh Woodward's parents are both proud and relieved that he got his GED and seems to be on the road to a stable career. His mother was a telephone operator but stopped working because of a disability. She finished high school and did some college, but never got a degree. His father, who dropped out of high school, worked in restaurants and auto repair shops. Now he takes care of his wife full time.

"We've been broke most of our lives," says Mark Woodward, Josh's father. "We really enjoy the fact that he's going to be able to take care of himself and his family a whole lot better than we did."

A program for veterans becomes America's second-chance diploma.

The GED was never meant to be America's second-chance diploma.

In 1942, Congress lowered the draft age from 21 to 18. America had been fighting in World War II for nearly a year. The change made an additional 2.25 million young men available for the war effort.

Over the course of the war, about 16 million Americans served in uniform. Some troops were drafted right out of high school, though local draft boards often let them finish their current term.

Don Kruse of Minnesota was an 18-year-old high school junior when he got drafted in June of 1945. The war had ended in Europe but the Allies were still fighting a brutal campaign in the Pacific.

"I thought maybe I could get into the Air Force and be a radio operator on an airplane," Kruse says. "That didn't happen."

Instead, he learned to be a radio repairman on the ground. As his term wound down, Kruse began thinking about college. He wanted to become an engineer. Like many other GIs, Kruse had gotten specialized technical training in the service. But he didn't have a high school diploma.

"You couldn't send 21-year-olds who had been in Germany, in the trenches, back into a regular high school. It just wasn't going to work," says H.D. Hoover, a retired University of Iowa professor and an expert on standardized testing. "The idea came along to say, 'OK, is there some way we can give these people some kind of credential to get them into university?'"

The military turned to an influential group of college and university presidents called the American Council on Education (ACE) to develop a battery of tests to measure high school-level academic skills. The tests were supposed to help returning GIs get credit for what they learned before and during the war. One of the test makers was a University of Iowa education professor named E.F. Lindquist.

Winners of the Brain Derby contest on the steps of Old Capitol at the University of Iowa. Photo circa early 1930s. Photo courtesy: University of Iowa College of Education.

Lindquist was the man behind a corn-belt academic contest launched in 1929. Iowa high school students took standardized tests to compete in a "meet" the way track stars and football players competed on the playing field. They became popularly known as the Iowa Brain Derby. Local schools would vie for top state honors.

E.F. Lindquist. Photo courtesy: University of Iowa College of Education.

But Lindquist had bigger ambitions than just creating an extracurricular contest for the studious. He wanted to open the narrow gates of American higher education to more students. His academic tests were designed to reveal areas where students needed extra help so they could work on those subjects until they qualified for admission.

Lindquist and his colleagues devised a series of assessments that would be widely used and imitated by other states: The Iowa Tests of Educational Development. This new set of tests would also be used as a template for the tests the military had asked for -- the GED.

The end of World War II wrought big changes in American higher education. In 1946, the president of the American Council on Education declared that returning veterans had forced "a permanent change in the evaluation of student achievement and competence." Time spent in the classroom had been the standard way to credential students. But ACE president George Zook said returning GIs wanted credit for "what they are, for what they know and for what they can do," rather than just for time spent in the classroom. The GED was the answer.

Veteran Don Kruse took the GED and passed easily. He used the credential to study engineering at a college in Wisconsin, which led to a long career. "I couldn't have gone to college without the GED," Kruse says.

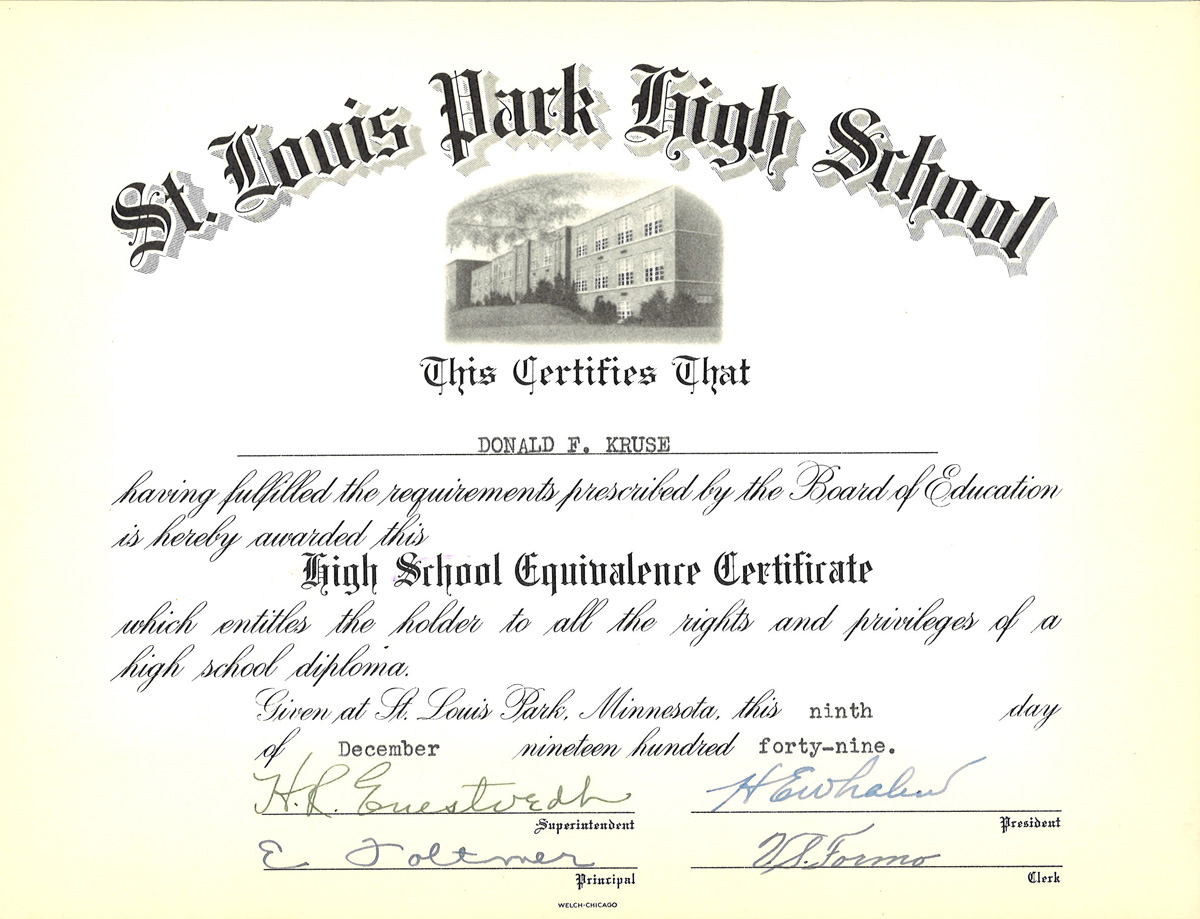

High School Equivalency certificate from 1949, awarded after Don Kruse took the GED.

The ACE calibrated the test to be easy, according to Lois Quinn, a researcher at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. Passing most sections of the test required answering only one or two more questions correctly than if you filled in the answer sheet randomly, Quinn says.

"The sentiment was that every person who served in the war should get a degree," Quinn says. "What the test did, possibly, was to weed out the people who were functionally illiterate."

As you can see in the illustration above, each time the GED test was updated (1978, 1988, 2002), there was a rise in the number of people who took the test before the update, and a drop the following year. This graph is not adjusted for population growth.

Two trends converged after World War II to accelerate use of the GED. Millions of returning vets wanted to take part in the generous higher education benefits offered under the recently passed GI Bill of Rights. The government would subsidize their tuition, books and living expenses. Veterans swamped the campuses of colleges and universities; many used the GED to gain admission.

The second trend was the enormous growth in intelligence testing. While mental testing for intelligence and achievement had been going on for decades, the scope of testing hit unprecedented levels in World War II and after. Many education experts of the era held a deep belief that standardized tests could revolutionize how human performance was measured and managed, in school and on the job.

"They were really quite convinced that there was a science of education. That learning could be measured. And that there would be tests to both examine as well as credential people, whatever their place in society," says William J. Reese, a historian of education at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. "The GED has to be seen as part of that larger story of how testing became so fundamental to American life."

Widespread use of standardized tests was made possible, in part, by a technical innovation perfected by Iowa's E.F. Lindquist: the optical scanner. Answer sheets that once had to be scored by hand could be fed into the machine for rapid processing.

"What the optical scanner did was immediately go from being able to score 200 tests an hour to 10 to 20,000 an hour," says H.D. Hoover. That meant millions of people could be tested each year at relatively low cost.

The GED began as a program just for veterans. But in 1947, New York became the first state to allow civilians to take the test. A quarter-century later, all 50 states were using the GED. Use of the GED boomed in the 1960s, fueled in large part by the expansion of social welfare programs under President Lyndon B. Johnson. The Job Corps and a variety of other federal programs in Johnson's "War on Poverty" began promoting GED certification as a way to produce high school graduates. Prisons began encouraging inmates to take the GED. And dropouts could qualify for some government assistance programs by getting a GED. By 1981, 14 percent of all high school credentials being awarded in the United States were GED certificates.

People take the GED test because they think the credential will help them get a better job or a college degree. But research shows earning a GED does not help most people do better in life.

D

emand for the GED grew throughout the 1970s and 1980s, accelerated by the changing economy.

The unemployment rate for 16- to 24-year-old high school dropouts rose steeply from the 1960s to the 1980s. By 1982 it was 28 percent -- compared with an unemployment rate of 17 percent for young people with high school diplomas. There were other ways for people who had quit high school to earn a credential, but no other alternative had close to the market share and name recognition of the GED. The test had become the way for dropouts to get a high school credential.

But the nation's largest employer -- the U.S. military -- lost faith in the GED.

Recruits at Lackland Air Force Base in Texas receive classroom instruction on the subject of liberty. June 1988. Photo by Robbin Cresswell. Source: National Archives.

At first, like everyone else, the military thought of a GED certificate as equivalent to a high school diploma. Then, in the 1970s, military researchers began noticing some disturbing trends in their data. People with GEDs were almost twice as likely as high school diploma holders to quit or be kicked out. Those with GEDs performed more like high school dropouts than like high school graduates.

Military leaders responded to this problem by requiring people with GEDs to have higher scores on the military's own test of cognitive skills, called the Armed Services Vocational Aptitude Battery, or ASVAB. GED recipients had to score higher on the ASVAB than people with high school diplomas to be accepted into the military. But even then, people with GED certificates were more likely to quit or be kicked out.

What military leaders realized is that successfully completing high school was a significantly better test of what it takes to make it in the military than doing well on an exam.

"First thing you do in the military after boot camp, you go to a classroom," says Janice Laurence, a professor at Temple University who studies the performance of GED holders in the military. "And you have homework. And you have to listen to a teacher. And you have to interact with your peers."

Laurence says these are the things many people with GEDs had trouble with in high school. For whatever reasons, they didn't make it in the structured environment of the classroom. And, as a group, they are more likely to fail within the structured environment of the military.

Military leaders realized that successfully completing high school was a significantly better test of what it takes to make it in the military than passing an exam.

Attitude, not just aptitude, has always been key to lasting success in the military, says Laurence. Department of Defense officials concluded that having a high school diploma was a better predictor of attitude than the GED. In the late 1980s, the military adopted selection policies that severely limit the number of GED holders who can enlist. Only in tough recruiting years do those restrictions get eased.

At about the same time the military was revising its policies on the GED, economist James Heckman got interested in the GED, too. In the late 1980s, Heckman was a professor at Yale. "I'd never heard of the GED," he says. "I mean, I guess I'd heard of it, but I knew nothing about it."

Heckman, now a silver-haired professor at the University of Chicago, tells the story of learning about the GED in a quick, excited clip. He was researching the effectiveness of a government job-training program. He went to Corpus Christi, Texas, and visited a job-training site at a community college. His guides took him into a classroom where students were taking a GED preparation class.

Heckman asked about the class. "They said, 'Oh, the GED is a miracle! In about six weeks, two months maybe, we're able to take people who had basically sixth-grade education, and we [can] convert them into high school graduates.' So you could get six years of education in about six weeks, something like that. I said, 'This is amazing!'"

Heckman was really excited. Think of what this could mean. Two months in a classroom and you could get a high school credential. The nation could save so much money on education!

Heckman wondered if it really worked. So he went back to Yale and started going through a big government data set that included people who had passed the GED and people who didn't have a high school credential.

"And I just asked the simple question: Do the GEDs do better than dropouts?" says Heckman.

And the answer -- a bit to his dismay -- was no. The data showed that passing the GED test did not, on average, help people do better in the labor market. People with GEDs were "statistically indistinguishable from high school dropouts," according to a 1993 paper Heckman published with one of his Yale graduate students, Stephen Cameron. "Both dropouts and exam-certified equivalents have comparably poor wages, earnings, hours of work, unemployment experiences and job tenure," they wrote. The dream of replacing high school with two months of test prep was dashed.

The 1993 paper wasn't the end of Heckman's interest in the GED; it was just the beginning.

"I got fascinated with this," says Heckman. "Too fascinated probably." He points to his current graduate students, Tim Kautz and John Eric Humphries, sitting next to him in his office at the University of Chicago. "We have a standing joke about Moby Dick," Heckman says. He is Captain Ahab and the white whale is the mystery of the GED: Why would someone who gets a GED not do any better in the labor market than a dropout?

Economist James Heckman (middle) with John Eric Humphries (left) and Tim Kautz. March 2013. Their book, "The Myth of Achievement Tests: The GED and the Role of Character in American Life," is scheduled for publication by the University of Chicago Press in Fall 2013. Photo: Emily Hanford.

It didn't make any sense, especially to an economist. The more education and credentials you have, the more employable you are, the more money you make -- this is what the data had always shown.

Something else the data suggest is that cognitive skills matter a lot. IQ, intelligence, smarts -- whatever you want to call it -- this is what economists and policymakers had been focusing on since standardized testing took off as a way to measure human performance back in the middle of the 20th century. Research shows the better you do on intelligence tests, the better you're likely to do in school and on the job.

That's not the case with the GED, though. Heckman's 20-plus years of research show that people who pass the GED test are just as intelligent, on average, as regular high school graduates who don't go to college. In other words, they're the same when it comes to cognitive skills.

But when it comes to "non-cognitive skills," there's a difference between GEDs and high school graduates, according to Heckman.

Cognitive skills are things such as memory, attention, reasoning and thinking. Non-cognitive skills include things like persistence, the ability to get along with people, self-control, and conscientiousness. Attitude. Showing up on time. Following the rules. The things the military is looking for in its recruits, and the reason the military is strict about admitting people with GEDs.

People who successfully pass the GED test tend to have higher cognitive ability, before they earn their GED, than people who drop out of high school and do not get a credential. Economists have shown that it's this cognitive ability, and not the GED credential, that allows some people who pass the test to make more money. When economists control for cognitive ability, they find that earning a GED does not, on average, result in higher wages.

Heckman and other economists hadn't traditionally accounted for these kinds of skills when looking at how people do in the labor market. They weren't even thinking about them. Heckman says economists called them "soft skills" in order to separate them from the "hard" cognitive skills they thought really mattered -- skills that could be measured on a multiple-choice test such as the GED or the ASVAB.

"We're a test-based society," says Heckman. "We think we know what it takes to succeed. A high IQ is the be-all and end-all."

But the lesson from the GED is that cognitive skills are not enough. What people prove by passing the GED test is that they have a certain level of smarts. They don't necessarily have the other skills they need to succeed.

"The goal of education, part of it, is that you are certifying a full set of skills," says John Eric Humphries, one of the graduate students working on a book about the GED with Heckman. "The GED is an interesting case because it's not the full set."

Passing a test is not the same as graduating from high school, says researcher Janice Laurence. As she puts it: "A diploma, by any other name, is not as sweet."

One of the most important questions about the GED, according to researchers, is whether the existence of the test encourages students to drop out of high school.

"If you provide people a middle option, some people will take it," says John Eric Humphries. He points to a government survey showing that nearly half of GED recipients say they dropped out, in part, because they thought getting a GED would be easier. Humphries questions whether 16- and 17-year-olds should be allowed to take the GED test at all.

"They can't vote. They can't drink. They can't smoke. They can't enlist. But they can make a very large life choice," he says. "It's unclear as a society that we want to allow someone to choose that middle route at such a young age."

Teenagers used to be barred from taking the GED test. In the late 1940s, most states established age restrictions in an apparent move to prevent young people from choosing to get a GED instead of finishing high school. You typically had to be 20 or 21 to take the test. But in the 1970s, officials at the federal Job Corps program wanted exceptions to the age requirement so younger dropouts could get a credential. By 1985, five states allowed 16-year-olds to take the GED, 10 states permitted 17- year-olds to take it, and eight more allowed exceptions for young test-takers under certain conditions. By 2008, 40 percent of all GED test-takers were between the ages of 16 and 19.

Why Students Drop Out

More than 40% of people who drop out of high school say they thought getting a GED would be easier.

Dropouts cite other reasons for quitting school too. A government survey asked people who don't have any high school credential and people who went on to get GEDs why they dropped out. Here are the most frequently cited answers:

| Reasons for Leaving School | Dropouts | GED Recipients |

| Thought it would be easier to get GED | 41% | 48% |

| Did not like school | 34% | 44% |

| Was getting poor grades/ failing | 39% | 39% |

| Missed too many school days | 42% | 39% |

| Not getting along with teachers/students | 32% | 27% |

| Could not keep up with schoolwork | 31% | 26% |

Source: Characteristics of GED Recipients in High School: 2002-06, National Center for Education Statistics, November 2011.

Some states actually offer GED preparation classes in certain high schools now. These programs target students at risk of dropping out and offer them the GED instead. Heckman's research shows that high school completion rates fell 4 percent in Oregon districts that introduced this kind of GED program.

The GED is "producing the very problem [it] was intended to solve," says Heckman. "It's creating a high school dropout problem."

Richard Murnane agrees. He's an economist at the Harvard Graduate School of Education who studies the GED. He notes that for much of the 20th century, the U.S. high school graduation rate steadily rose. Between 1900 and 1970, the rate went from 6 percent to 80 percent. But then it stagnated. There was essentially no growth in the high school graduation rate for 30 years. Murnane wrote in a recent paper that the GED is, at least in part, to blame:

"The availability of the GED credential leads some teenagers to drop out of school who otherwise would have persisted to graduation. Its increasing availability to teenagers between 1970 and 2000 likely contributed to the stagnation of the high school graduation rate."

Between 2000 and 2010, the U.S. high school graduation rate rose six percentage points. And since 2002, the percentage of GED test-takers who are 16- to 18-years-old has gone down. It's not clear to researchers exactly why these two things happened, or whether there is a connection.

The GED Testing Service, also known as GEDTS, owns and operates the GED. It's a partnership between the non-profit American Council on Education, which has been running the GED since 1942, and the for-profit publishing company Pearson.

"The Bible and a GED preparation book are the two things you're always going to find in every library."

- CT Turner

CT Turner, director of public affairs for the GEDTS, says the idea that the GED encourages some students to drop out is "absolutely false." He points out that people quit high school for many different reasons; research shows that family problems, bad schools, and living in poverty all put kids at significantly higher risk of not finishing high school.

When asked about the research suggesting many people with GEDs lack non-cognitive skills such as persistence and the ability to get along with people, he responds that those skills are hard to assess.

"Right now there's no test that adequately measures those softer skills," he says.

Turner says the GED is reliable, scalable and cost-effective. That's why it's so popular, he adds. More than 20 million Americans have passed the GED test since it began in 1942. "I was just at the American Library Association Conference and I heard a librarian tell me that the Bible [and] a GED preparation book are the two things you're always going to find in every library," Turner says.

Turner says the purpose of the GED has always been to give high school dropouts a second chance. And they need that second chance now more than ever, he says.

"A high school diploma, back in the day, was sort of the gold standard," Turner says. "If you had a high school diploma, you worked hard, you could probably have a good life, maybe get a house on the lake, you could support your family, everything's great."

But things have changed. Turner cites a report by the Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce that predicts 63 percent of jobs are going to require some education or training beyond high school by 2018. He says everyone needs to recognize that getting a GED isn't enough, and it's up to teachers and counselors at GED prep programs and adult education schools to communicate that message. "We have to transition the GED test away from an ending point. It has to be a stepping-stone to the next thing," Turner says.

Currently, the GED serves as a stepping-stone for very few people. About 40 percent of GED recipients go to college; among those who go, 65 percent complete just two semesters or less. Only 3 to 4 percent earn a bachelor's degree; 5 to 9 percent complete an associate's degree.

"Many students earn a GED because they think it'll allow them to graduate from college," says Tim Kautz, one of the researchers working on a book about the GED with economist James Heckman. They get a GED and they think, "Great, I'm equivalent to a high school graduate. I'm going to go to college. I might leave my current job, pay tuition. And then they realize they just don't have the skills to succeed in college."

A lack of non-cognitive skills may not be the only reason GED recipients struggle to make it in college, Kautz says. They may not have the cognitive skills they need, either, since the GED only tests knowledge at about a ninth- or 10th-grade level.

Kautz says the GED deceives dropouts; to get a second chance, they need more than a test.

The GED has become a basic, minimum requirement for most jobs. But passing the test is a big struggle for many people, especially older adults who have been out of school for a long time.

For many people, the GED is a relatively easy test to pass. They study for a few weeks or months. They might take some classes or buy a GED test prep guide and study by themselves. According to the GED Testing Service, about half the people who take the test study on their own.

There is a lot of research, from economist James Heckman and others, about people who pass the GED test. Much less is known about people who try to get a GED but don't succeed. More than 700,000 people took the GED test in 2012. Forty percent didn't pass.

People who pass the GED test tend to be young (average age: 25). They've been out of school less than a decade (average number of years out: 8). And they made it at least halfway through high school. (Thirty-seven percent completed at least 11th grade. Twenty-eight percent completed 10th grade.)

Many of them are older adults who quit school long ago. When they dropped out, there were still decent jobs available for people with no high school credential.

"They were getting paid $15, $16, $17 an hour," says Daquanna Harrison, education director at an adult education program in Washington, D.C. called Academy of Hope. "And then the economic system crashed. Everyone needed a reason to get rid of them and they looked and saw, no high school diploma. Outta here!"

Harrison says that for decades it's been getting harder for people with no high school credential to make it in the workforce, but the most recent recession was especially tough on them. Charles Gibson, a student at Academy of Hope, says he used to work as a janitor and a security guard but can't get those kinds of jobs anymore.

"Every time I be looking in the want ad section of the newspaper, I see, 'Must have a high school diploma or a GED,'" he says, shaking his head. Gibson dropped out of school in the 10th grade. That was 1975.

"Man, you got experience," he would say to himself while looking through the want ads, "But you ain't got no high school diploma or GED. I heard that so many times, I say, 'I'm going back to get it. The heck with that, I'm going back to get it.'"

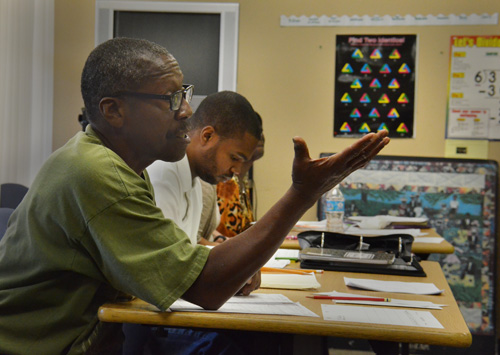

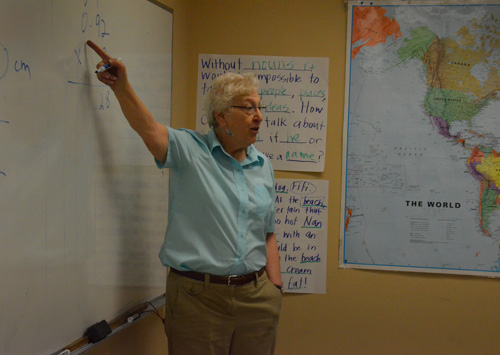

Math class at Academy of Hope. Photos: Emily Hanford

Gibson started at Academy of Hope in 2008 and says he's not stopping until he gets his GED. "I call it my willpower," he says, turning his typically shy smile into something steelier. "My willpower keeps me going every day."

He says he didn't have this kind of willpower back in high school. He hung around with the wrong crowd, skipped class a lot, wasn't motivated about school. "I have to blame myself" for dropping out, he says. He calls it a dumb move by a kid who didn't know better. Now he knows better.

Academy of Hope is an adult education program that started in 1985 in the empty guardroom of a low-income apartment building in the Adams Morgan section of Washington, D.C.

"We paid $50 a month for the guardroom," says co-founder Marja Hilfiker.

1985 photo of Marja Hilfiker, left, with Academy of Hope cofounder Gayle Boss, right, and the school's first GED graduate, Linda Brown Myrick. Photo courtesy: Academy of Hope Archives.

There were four students at the start. The students and teachers held bake sales to help pay the rent. Hilfiker and her co-founder, Gayle Boss, belonged to a church together. This was their mission. They bought what Hilfiker describes as a "big, fat" GED test prep book and they started teaching. Classes were three days a week. Students invited their friends and neighbors. "It was very family-like," says Hilfiker.

Eventually, they ran out of room and moved to a bigger space. Today, Academy of Hope is located in a community space that's part of a large apartment complex about two miles northeast of Capitol Hill. At any given time there are roughly 150 students enrolled.

Academy of Hope is not officially a school, but it feels like one.

There's a snack bar that sells chips and sodas during lunch. There are field trips, potlucks and an annual holiday party. There are writing contests and awards ceremonies. There was once talk of planning a prom. Students are here not just to prepare for a test. They're here to get what they didn't get in high school.

It's the Monday before Thanksgiving and students are learning about the Powhatan Indians in social studies class. The Powhatan lived near Jamestown, Virginia when the English first settled there in 1607.

Charles Gibson is in this class. He's studying a map the teacher has handed out. The map shows how Native Americans first came to what is now the United States, by crossing the Bering Land Bridge. The teacher asks why they did that and Gibson raises his hand.

"They were following their prey," he says.

"Exactly!" says the teacher.

Another student in this class is Jean Griggs. She says she likes social studies because "I never had the opportunity to learn about stuff like that."

Jean Griggs at home with Jalisa Parker, her son's girlfriend. Parker is helping Griggs with her Academy of Hope math homework. March 2013. Photo: Emily Hanford.

Griggs is 55. She went to D.C. public schools in the 1960s and '70s. She says a lot of the teachers didn't care if students learned anything.

"They never were in the classroom," she says. They'd start class, give students a worksheet, and leave. "Then, like maybe five minutes before the bell rang, here they come and they say, 'You finished with your papers?'" She raises her voice, yelling the way she remembers the teachers yelling at the class.

Griggs says the work got really hard for her in high school. When she couldn't figure something out, there was no one to help her. Math was especially tough.

She remembers meeting a girl named Maria in her 10th-grade math class. Maria sat next to Griggs and helped her do the work. With Maria's help, Griggs could keep up. But then one day, Maria was gone.

"I looked for her, and there was no Maria," Griggs says, taking a long pause to collect her emotions. "I was lost in the sauce," she says, tearing up. "And I knew I was failing."

Griggs stopped going to school. She got up every day and pretended to go. The school sent letters home, but Griggs intercepted them. She says no one ever called. Her mother didn't find out Griggs had dropped out until she finally admitted it two years later.

When Griggs started taking classes at Academy of Hope more than a decade ago, she says she was below a fifth-grade level in math and reading.

Like Griggs, almost all of the students at Academy of Hope have completed at least some high school. But only 8 percent of them read and do math at a high school level.

Carlita Johnson (left), with Academy of Hope students and staff, at the D.C. Council building to lobby for more funding for adult education programs in the city. May 2013. Photo: Emily Hanford.

Carlita Johnson always thought of herself as a slow learner. She quit school in 10th grade. Now she's 50. She works as a cashier but she wants to go to college and become a respiratory therapist. Johnson's been a student at Academy of Hope for eight months. Today is a big day because she just moved up a level in math.

"I'm in decimals, finally!" Johnson giggles and a huge smile breaks out across her face. "It's quite an experience. I'm learning things that I never thought that I could learn."

The lowest level math class at Academy of Hope is Whole Numbers. Then it's Decimals, then Fractions, then Ratios, Percents and Analysis. Finally there's an Algebra and Geometry Basics class. Once students can score close to a 10th-grade level in math on a standardized test called CASAS, Academy of Hope says they're ready to take a GED practice test. Johnson's goal is to pass the GED by January of 2014. That's just over a year away.

"I've got to get things going on with my life," she says. "I need to pursue a career that will offer me benefits. Long-term benefits. I don't want these things. I need these things."

Jean Griggs needs her GED too. She used to be an assistant teacher at a government day care center. But in 2011 she lost her job. It was part of a change in child care accreditation requirements: All teachers must have a high school credential now. Griggs doesn't understand why.

"I've been working with kids for almost 17 years!" she exclaims. "I know how to take care of infants. I know how to change [diapers], I know how to do CPR."

Griggs has been on unemployment but it's going to run out soon. She says she applies for jobs all the time, but everyone says the same thing -- come back when you have your GED. She's beginning to wonder if she'll ever get it.

"I hate the word 'can't,' says Griggs, "because I keep on trying. I keep trying and trying and trying and it doesn't seem..." She pauses and sighs, "... like I'm catching it."

Every Wednesday Academy of Hope invites guest speakers to talk during lunch. It's a potluck. Today there's tuna salad, macaroni and cheese, and homemade soup.

"You don't need to write essays or know algebra and geometry to clean hotel rooms. I know lots of people who are excellent workers. But meeting the GED requirements is a long stretch for them."

- Academy of Hope co-founder Marja Hilfiker

The speaker is Ron Harris, an organizer for ONE DC, a community group that advocates for health care, housing and jobs for the city's low-income residents. He's got a baseball cap on and a clipboard in his hand.

"I'm here to talk about jobs," Harris begins.

Harris tells the students about a new Marriott Marquis hotel scheduled to open in downtown D.C. in May of 2014 -- 18 months from now.

"You say, 'Why he talking about jobs in 2014? I need a job now!' Right?" Harris pauses like a preacher, waiting for the audience to respond. "Right," says one student. "Uh-huh," says another.

Harris explains that Marriott has agreed to set aside about 400 jobs for D.C. residents, as part of a deal to build the hotel on city-owned land. He says Marriott is expecting to test 3,000 people to make the 400 hires. Background checks and drug tests will be required. Applicants will even have their credit scores checked.

A student asks if a GED is required.

"Marriott says it's not mandatory," Harris says, but he shakes his head expressing doubt. "I talked to a guy who manages a hotel. He said they're going to tell you it's not mandatory, but if you don't have it, they're not going to hire you." He pauses again. "So let's be real, OK?"

Marriott declined a request for an interview.

A student asks what the jobs will pay and Harris says at least $13 an hour.

"I can live with that," she says.

"I can live with that too," says another student.

A Tale of Two Cities

Washington, D.C. has the lowest high school graduation rate in the nation: 59%. [source]

An estimated 19% of D.C. residents lack basic literacy skills. [source]

D.C. also has the highest bachelor's degree attainment rate: 49%. [source]

Marja Hilfiker, the Academy of Hope co-founder who organizes these lunch meetings, wonders aloud if Harris can go back to Marriott and ask if it would be possible for at least some of the jobs not to require a GED credential.

"You really don't need to write essays or know algebra and geometry to clean hotel rooms," she says. "I know lots of people who are excellent workers and show up every single day. But meeting the GED requirements is a long stretch for them."

Harris says there's not much he can do.

He says later that he believes using the GED as a way to screen job applicants has the effect of denying opportunities to poor, minority workers. Employers may not do this deliberately, he says, but that's the effect. He says there are virtually no jobs in D.C. for people who don't have at least a GED.

The only choice for students at Academy of Hope is to pass the test.

Alejandra Johnson, a student who's been listening to Harris talk, says she'd really like to get one of the Marriott jobs.

"I've been praying," she says with a sigh. "I've been getting on my knees and saying, 'God, please give me a sharp mind to pass this test.' And He will do it," she says. "He's going to come through for me. I got a lot of studying to do when I get home." She pats the fat book bag on her lap. "I gotta do it. And I'm gonna do it."

A new, more rigorous GED test may make it harder for millions of high school dropouts to get a credential. In response, some states are giving up the GED and opting for other exams.

I

t may soon get more difficult to get a GED. The GED Testing Service (GEDTS) is launching a new GED in January 2014. Public affairs director CT Turner says the updated test will be more rigorous because the skills required for today's jobs have increased.

"This is about: What is the workforce demanding and what does an adult need to really be prepared and have a fighting shot at getting [a job] that's going to support themselves and their families?" he says.

Turner says the decision to change the test dates back to 2009. The American Council on Education (ACE), an association of college presidents that has administered the GED since its inception, was getting ready to revise the test. The GED had been updated three times before. But those were relatively minor changes compared to what ACE officials were thinking about now.

In 2009, ACE officials were reviewing data that show how few GED recipients go on to college and graduate (only 5 to 9 percent earn an associate's degree; 4 percent earn a bachelor's). They were also concerned that most GED recipients who go to college need remedial classes.

Even students who make it through four years of high school often need to take remedial classes when they get to college. GEDTS studies show that 40 percent of graduating high school seniors could not pass the GED test. (There is some dispute about these studies. The GED is given to a random sample of graduating seniors, who don't necessarily have an incentive to try very hard on the test.)

Still, ACE officials concluded that the current GED is not preparing people for higher education, and higher education is what people need to make it in today's economy.

At about the same time, another group of educators and policymakers concluded that America's K-12 schools needed more rigorous tests, too.

In 2010, the National Governors Association and the Council of Chief State School Officers released the Common Core State Standards, a set of expectations about what all American students should learn in school. Forty-five states and the District of Columbia have agreed to adopt these standards, along with new, harder tests that will be used to show how students are performing.

ACE decided that if high school was going to be harder, the GED should be too.

CT Turner says the new GED test will require "higher order thinking." There will be more questions that require written responses and fewer multiple-choice items. For example, in the new social studies section, a test-taker might read an excerpt from President John F. Kennedy's inaugural speech. Turner says the question might ask the test-taker to explain in a paragraph what Kennedy meant by a particular passage. "So people are going to have to think critically and then they're going to have to actually write about it."

Something else that will be different about the new GED: It will be available only on computer. No more paper and pencil tests. According to Turner, scoring the computer test will be faster and more sophisticated. Test-takers will get score reports with detailed information about what they did well on and where they need work. Turner says this will allow people who don't pass to study more effectively before taking the GED test again.

There will be two passing levels on the new GED. One will indicate that a person meets the requirements for a high school credential. A higher passing level will indicate that a person is ready for college.

The new test will cost $120, more than what it costs states to administer the current GED. The amount test-takers pay varies because some states subsidize all or part of the fee. CT Turner says updating the GED required $40 million in new investment. That's why ACE created a partnership with for-profit publisher Pearson in 2011, he says.

How Will the New GED Be Different?

Computer-only

The new GED will be available only through a proprietary computer program at authorized test centers.

Common Core-aligned

The new GED will have four sections, not five. It will test literacy, math, science and social studies. Writing will be assessed across subject areas. There will be more written responses required and fewer multiple-choice questions.

Two passing thresholds

A certain score will be required to pass the test and certify high school equivalency. A higher score will demonstrate readiness for college.

Cost increase

It will cost $120 to take the new test. The amount test-takers pay will vary by state, because many states subsidize all or most of the fee.

The bump in price upset many state officials who oversee GED policy. "Their memo about prices panicked the herd," says Troy Tallabas, a GED administrator in Wyoming, referring to the announcement by GEDTS to raise the test fee.

State officials were also concerned about the decision to require everyone to take the GED on computer.

"We were surprised we were being told this rather than having this discussed with us," says Kevin Smith, the deputy commissioner of Adult Career and Continuing Education Services in New York State. Smith says there are 269 GED testing centers in New York, and none of them have any computer equipment available for testing. He says some centers don't even have sufficient electrical power to turn on dozens of computers at one time.

Smith and other adult education directors say many GED seekers may not be ready to take a test on computer. And they may not be ready for a more difficult test. The changes were too much, too fast, says Smith.

In 2011, Smith and adult education directors from several other states formed a working group to discuss getting rid of the GED and coming up with alternatives.

As of early September 2013, the working group counted 41 states among its members. Six of them have announced that they will no longer offer the GED once the new test is released in January, 2014. Those states include New York -- the first state to offer the GED to civilians back in 1947 -- and Iowa, the birthplace of the GED.

Iowa is replacing the GED with a high school equivalency test being developed by the Educational Testing Service, a nonprofit company that produces other widely used standardized exams, including the SAT and the GRE. New York is working with for-profit testing company CTB/McGraw Hill. Both the ETS test and the CTB/McGraw Hill test will be available on paper, though the goal is for most people to take the test on computer eventually. New York state officials asked that the difficulty of the new high school equivalency test be phased in over time. "We have to give people a chance to get the instruction and the support in order to have a chance to pass the exam," Smith says.

But even with instruction and support, people will still have to pass a test. And even if the test is harder, GED critics say no test can certify that someone has the skills of a high school graduate.

A high school diploma means "we have some smarts and we know some stuff," says Janice Laurence, a GED researcher at Temple University. "But beyond that, it also means ... ways of acting and functioning in society" that a cognitive skills test "doesn't take into consideration at all."

When asked about the new GED test coming in January of 2014, Academy of Hope student Charles Gibson shakes his head. "I'm sorry they came up with that," he says with a nervous laugh. "A lot of other people are sorry about that too."

Gibson doesn't have much experience with computers. He's not sure he could pass a test that's offered only on computer.

The new GED test will create another challenge for some test-takers, too. People who take the GED and fail some of the sections are allowed to retake just the sections they failed. But starting Jan. 2, 2014, when the new GED test debuts, everything resets. If someone hasn't passed all sections of the current test by then, they will have to start over with the new test.

Charles Gibson doesn't think that rule will apply to him anyway. He says he won't be ready to take the test -- at all -- until 2014.

Some people study for the GED for years, but they still can't pass the test. What's the value for them?

I

n April 2013, Jean Griggs, a student studying for the GED test in Washington, D.C., gets a notice in the mail from the city's Department of Employment Services: She must come to a special information session if she wants to continue receiving her unemployment check. She gets $181 a week after taxes.

Griggs shows up for the session early. It's being held in a building that used to be a middle school. She sits in a waiting area with a big folder full of notes that document her job search. Her son's girlfriend has been helping her post this information online, but Griggs brings the hard copies anyway. She's not sure she trusts the online system.

Jean Griggs outside a D.C. Department of Employment Services office in northeast Washington D.C. April 2013. Photo: Emily Hanford.

Her notes show she has applied for dozens of jobs in the past few months. Target, Wendy's, a barber shop called "Dee's." Griggs used to cut hair, but she hasn't done that in a while. She wants to work in child care; she worked in a government day care center but lost her job in 2011 because the center changed its policies to require that all teachers have a high school credential. Griggs got one interview for a nanny job but it would have meant a long commute and unpredictable hours. She would have done it, but the job would have also required her to quit school. Griggs is determined to get her GED.

Griggs gets called in to the information session. She walks down a hall lined with lockers to what was once a classroom.

At first it's standing-room only, but after the session leader goes over a list of documents attendees are required to have with them, about a dozen people walk out, leaving 28 people in the room.

Everyone here is on long-term unemployment, a special extended-benefits program approved by Congress in response to the recession.

The session begins with a PowerPoint presentation. Attendees learn that the federal budget sequester will soon reduce everyone's benefits. Checks will be cut by more than 10 percent. They're also told that long-term unemployment benefits are scheduled to expire in January of 2014.

"It's very difficult out there right now," says the session leader, referring to the economy. He gets a couple of "uh-huhs" from the audience. He says his goal today is to make sure everyone has the information they need to "match your career skills with current labor market demands."

He lets them know about services offered at the unemployment office: a resume-writing workshop; a workshop on successful interviewing; a computer skills class. He also tells them about some job-training programs, and reminds them they must bring proof that they have a high school diploma or a GED.

One of the most important things to remember, says the session leader, is that "persistence breaks down resistance." He has it written on one of his PowerPoint slides. The slide also says, "Recognize your deficiencies and increase your strengths!" Another slide says: "Success is a Choice, Not a Chance."

When the session is over, Jean Griggs meets with an employment counselor who introduces herself as Ms. Parker. Griggs tells her she is in school to get her GED and Parker, still looking down at Griggs's paperwork, says, "Oh, that's good."

Griggs says, "When I go look for jobs, I need that piece of paper."

"Exactly," says Parker. "And what are your employment goals?" she asks.

"Once I finish my GED?" asks Griggs. Parker looks at her without answering.

"Ah, go to college," says Griggs, sounding uncertain. She pauses for a moment and then says, "I just want a job."

Parker smiles at her reassuringly. "Now, once you receive your GED, you can come back here and we can assist you with your occupational skills," she says.

Parker goes through Griggs' job search paperwork (it's good a thing she brought it with her because Parker is set up at a temporary desk in the hallway with no access to the online system where Griggs has been submitting her job search information). Parker looks at a copy of Griggs' resume. She recommends Griggs come back for the resume-writing workshop. Griggs nods yes.

Parker says getting a GED will open up a lot of job possibilities for her.

"What if I never get my GED?" Griggs asks.

Parker looks a bit startled. "What do you mean, if you never get it?"

"It's a long story," says Griggs, brushing off the question. She changes the subject.

Outside in the bright April sun, Griggs takes a deep breath and remarks on a quote that was on one of the PowerPoint slides earlier. "I think I can, I think I can," it said. "But," she says, "something in the back of my mind makes me think I might not."

Jean Griggs has been taking classes off and on for more than ten years to prepare for the GED. When she started, she says she was below a fifth-grade level in reading and math. Her reading skills have improved. Tests that students at Academy of Hope take every few months show that by the spring of 2013, Griggs is at an eighth-grade level in reading. But she's still at a fifth-grade math level.

Why People Want a GED

Most people get a GED because they want more education or a better job, but the overwhelming majority of them also do it for personal reasons.

| Reasons for obtaining a GED credential | |

| Meet requirements for additional study | 66% |

| Train for a new job/career | 51% |

| Improve/ keep up to date on current job | 47% |

| Improve basic reading/writing/math skills | 36% |

| Required or encouraged by employer | 23% |

| For personal/family/social reasons | 71% |

Griggs thinks she has a learning disability. In the late 1990s, she attended a program for adults with learning disabilities, but as far as she knows she was never officially diagnosed with a problem. Then the funding for the program was cut. More recently she went back to another social service agency and was referred for testing. She says the tests show she does have a learning disability. She's met with counselors at the agency but she says they often don't return her phone calls and it's not clear to her how they will be able to help her anyway.

Research shows that about a third of public school students who have learning disabilities leave high school before graduating. Many of these students enroll in GED preparation and other adult education programs. The percentage of students in these programs who have learning disabilities ranges from a conservative estimate of 15 percent to as high as 80 percent.

Lecester Johnson, executive director of Academy of Hope, says, "We have a lot of people in our program that we suspect were never identified [as learning disabled] when they were in school. They've had terrible experiences in terms of not getting their learning needs met."

Jean Griggs laughs when asked if any of her teachers or counselors growing up suggested she be tested for a disability. "They never called my mother to say I was having a hard time with anything," she says.

Griggs likes attending Academy of Hope. It makes her feel good to get up every morning and go to school. She likes the teachers and the students. And she likes learning. One of her science classes had a unit on nutrition and she says it inspired her to eat more vegetables; she says she's lost 10 pounds. She also won first place in a writing contest. Her winning essay began with a quote from basketball legend Michael Jordan: "I have failed over and over again in my life, and that's why I succeed."

Griggs says she needs her GED, and she's going to keep trying. She says the staff at Academy of Hope knows about her learning disability. When she meets with her advisor, Elizabeth Winn Bowman, in May of 2013, Griggs brings it up.

"I guess I just learn different," she says, tears coming to her eyes.

"Lots of people here learn differently," says Winn Bowman, handing Griggs a tissue. "We're going to come up with a plan, OK?"

Winn Bowman tells Griggs about an alternative high school credential program that she thinks might work better for her than the GED. It's called the National External Diploma Program (NEDP). It's been around since 1975, but it's much smaller than the GED. Only about 4,500 people are in the program in a given year. And it's offered in just six states -- plus Washington, D.C., so it is one of the options available to Jean Griggs and other students at Academy of Hope.

Winn Bowman describes the NEDP to Griggs. It's a "competency-based" program. You work one-on-one with an assessor who gives you a series of assignments. Making a household budget, for example, or going to a play and writing about it. You complete the assignments over several weeks, months -- or even years. You have to work on them until you get a perfect score. It's much different than sitting down for a seven-hour GED test.

The NEDP sounds like it might be a good option for Griggs; she's already demonstrated she's willing to work hard. But here's the kicker -- to be eligible for the NEDP, Griggs will still have to bring her math scores up by about five grade levels. She leaves the meeting with a headache.

There are two groups of people when it comes to the GED test: You can think of them as the passers, and the strivers.

A lot of people studying for the GED have learning disabilities. "They've had terrible experiences in terms of not getting their learning needs met."

- Academy of Hope Executive Director Lecester Johnson

For most of the passers, the test is relatively easy. They may study or take classes for several weeks or months. They take the test once -- maybe they have to take some sections of the test a few times -- and they're done. This is the larger group. GED Testing Service data show that 85 percent of the people who took the GED in 2012 were trying it for the first time; 75 percent of them passed.

The GED passers may have the cognitive skills of a high school graduate, but according to economist James Heckman and other researchers, what many of them lack -- or at least what they lacked when they were younger -- are the skills to make it through four years of going to class, doing homework, and getting along with teachers and peers.

For this group, the GED credential isn't much more than a piece of paper, according to critics. It may help someone get to college. But the vast majority of GED recipients don't make it through college. The GED may also help someone get a job. But data show that, on average, GED recipients are more likely than high school diploma holders to quit or be fired from jobs. In other words, they may get jobs, but they don't necessarily keep them, reducing their overall earnings to about the level of high school dropouts.

Critics of the GED say most people who quit high school but can pass the GED test relatively easily need help developing non-cognitive skills, and a test does not help them gain those skills.

People in the other group, the GED strivers, struggle with the test. Some of them study for years, but passing is a stretch. It's been a long time since they wrote essays or did algebra problems. Maybe they went to bad schools and no one really taught them writing or math. Perhaps they have learning disabilities; some of them may not even know it. For the strivers, the GED test is a big barrier. They may be hard-working, persistent people, but until they pass the test, they may not get a chance to show employers what they have to offer.

There's very little research about this group of people. The GED Testing Service reports that in 2012, about 15 percent of test-takers had tried the GED at least once before. That's approximately 105,000 people, not counting the thousands, or even hundreds of thousands, of people who study for the GED for months and years but never take the test.

Is there any value in studying for the GED for a long time, especially since research shows the credential does not actually help most people do better in the labor market or higher education?

There's not a clear answer to this question.

Some researchers say if the process of studying for the GED gives people skills they didn't have before, it may help them in the labor market. But the findings here are slim and contested. A study published in 2000 found that for young, white high school dropouts with relatively low cognitive skills, getting a GED credential increases earnings by 10-19 percent. According to the study, getting a GED helped this group of people increase their annual earnings from an average of $9,628 to $11,101, five years after getting a GED credential. But as the authors note, $11,101 was still well below the poverty level for a family of three in the mid-1990s, when the study was done. These findings have not been replicated by other researchers, and economist James Heckman disputes the study on technical grounds.

Most people who study for the GED aren't doing it just to get a better job or more education. They're doing it because they also want to finish something they failed to finish years ago. In government surveys, 71 percent of GED recipients cite personal, family or social reasons for why they took the test. That's the most frequently cited answer.

Academy of Hope student Charles Gibson says he's determined to pass the GED so he can say, "Yeah, I finally got it. I finished." It's something he's wanted to say for more than 30 years. Even if he doesn't pass the test, Gibson says studying has made him feel like a more educated person. "I feel good about myself," he says.

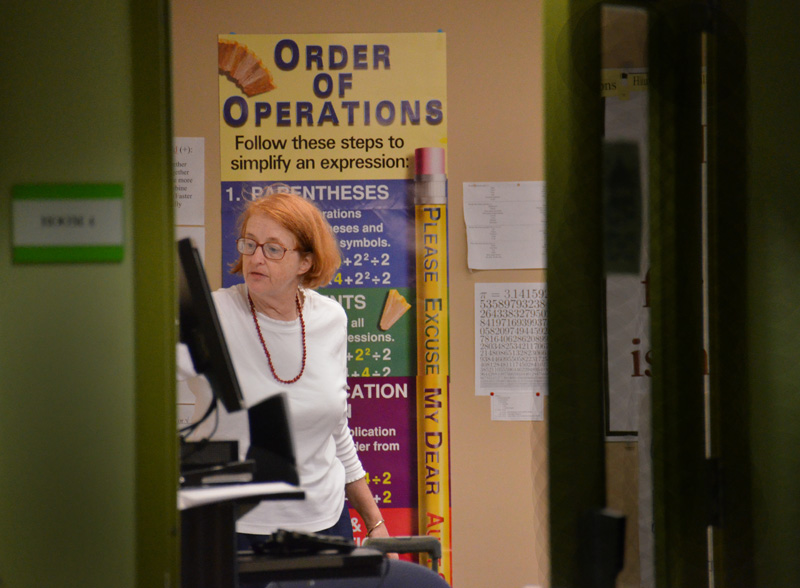

A math teacher at Academy of Hope. July 2013. Photo: Emily Hanford.

Student Carlita Johnson says she feels like a more educated person now, too. She says she's better able to "adjust and adapt in conversations with all classes of people. And that's a very comforting and overwhelming feeling." Before, she just wouldn't talk much around people who were more educated than she was. "Now, I can generate my own conversation!" she declares gleefully.

Johnson started taking classes at Academy of Hope 15 months ago. She began in the lowest level math class and has gotten her scores up to a tenth-grade level. Her adviser tells her she is ready to take a GED practice test.

But Johnson has decided to try the National External Diploma Program instead. That's the competency-based high school credential program. Johnson says she thinks doing projects will give her more of a sense of accomplishment than taking a test.

"The more that I accomplish, the more that I want to accomplish," she says. "And the more determined and confident that it makes me that I can accomplish" things.

Johnson is about to turn 51. She says this is the first time in her life she's felt that if she worked really hard at something, she could succeed.

"It's a total new feeling," she says. "And it makes me feel like the sky is the limit now. You know, like I can do and be and accomplish anything that I set my mind into doing. Just like other people in society."

Critics say the GED is not a good solution for people who dropped out of school. But it's not clear what's better.

I

t's graduation day for students in the Kirkwood Community College high school completion program in Cedar Rapids, Iowa.

Josh Woodward pulls a thin blue gown out of its plastic wrapper and pulls it over his head, hiding the shorts and black t-shirt underneath. Across the hall, Chad Phelps places the blue and white tassel on the right side of the mortarboard perched atop his head. Once he gets his GED certificate, he'll flip it to the left side -- that's the protocol once you're a graduate.

Woodward and Phelps line up with all the other graduates in alphabetical order, readying themselves for the processional. The ceremony is held in a hockey arena. The rink is covered with wooden boards, and rows of chairs have been set up for the graduates. Phelps's family gathers in the bleachers. They plan to stop at Dairy Queen on the way home to celebrate. His grandma bought a card and slipped $20 in the envelope.

Josh Woodward at the Kirkwood graduation ceremony for GED recipients at the ice arena in Cedar Rapids, Iowa. May 2013. Photo: Stephen Smith.

Josh Woodward is here on his own.

The graduation ceremony on this mild Friday evening in May honors 536 students. Most of the graduates are adults. A lot of them have kids. A few are old enough to have grandkids.

When Chad Phelps' name is called his family whoops in appreciation. He grins as he takes the stage to get his GED certificate. His grandfather, Doug Nightingale, looks on, proud and a little bit worried.

"I think it's harder for the kids today than it was for us," Nightingale says. He dropped out of high school but had a long, stable career as a truck driver for a big dairy company. "There's so much stress in the workplaces today," he says, "and there's no certainty that you're going to be with whoever you're working for any more than five or 10 years. Then you're going to be looking for another job."

His grandson Chad plans to start college at Kirkwood and study audio engineering. He'd like to work in the music or film industry, maybe out in California. "Anything like that," Chad Phelps says. "I want to do something I enjoy on a regular basis, instead of hating to go to work."

Josh Woodward wasn't planning to come to graduation. He says he's more of a behind-the-scenes guy. But he wanted to demonstrate his respect for the people who helped him through. "I'm truly proud of getting my GED," Woodward says.

Woodward is working on a two-year degree in advanced manufacturing at Kirkwood Community College. He had a paid internship at a machine shop and was hoping to get a college scholarship the company offers. But he quit after a couple of months. He was in class for four hours in the afternoon, then working at the internship from 6:00 to 11:30 p.m. "I was running a 16-hour day," he says. It was exhausting, plus he was having some family problems he doesn't want to talk about.

Chad Phelps attended the graduation ceremony for GED recipients at the ice arena in Cedar Rapids, Iowa. His mother, grandparents and nephew cheered for him from the bleachers. May 2013. Photo: Stephen Smith.

"I wasn't there for a job. I was there for a learning experience," says Woodward. "I think I used it to the fullest extent."

On the face of it, Woodward's decision might seem to fit economist James Heckman's finding that people with GEDs are less likely than people with high school diplomas to stick with jobs and other opportunities. But when research using big data sets meets the reality of daily life at the lower end of the economic ladder, broad statements get complicated by the particulars of struggling to survive.

"My plan is to keep working my butt off," Woodward says. "Then find out what's next."

When the GED was created back in the 1940s, a lot of people believed that cognitive skills -- smarts, IQ -- were the most important skills for success in school and on the job. But a wide body of research in psychology and economics now shows that for many important life outcomes -- including how well people do in school and in the labor market -- non-cognitive skills are just as important, or even more important, than cognitive skills.

"Non-cognitive skills have a return at all types of jobs," says GED researcher Tim Kautz. "Everybody needs to show up to work on time to be successful."

Cognitive ability matters too, but it "has the highest return when you're in a high-skilled job," he says.

As an alternative to high school, the GED is selling a huge portion of the population short.

- Researcher Lois Quinn

The irony of the GED is that it may be screening out the very people that employers need to fill low-skilled jobs: people who are reliable, hard workers -- but don't necessarily have the cognitive skills to pass a high school-level test.

The GED isn't helping a lot of the people who pass the test either, according to critics. If someone doesn't have the non-cognitive skills that can help them perform well in the job market, they need to learn those skills, says economist Jim Heckman. The good news, he says, is research shows that people can learn those skills.

"That's in contrast to cognitive skills, which are more fixed," says Heckman.

He says the widespread use of the GED test is a consequence of the "pervasive belief" that achievement tests are good measures of people's capabilities. It's a belief that's been central in American education and public policy since the 1940s, when standardized testing started to take root, says Heckman.

"I would say it's now willful ignorance," he says, "saying the achievement test is the be-all and end-all, the measure of the person."

So if the GED test doesn't help most high school graduates, should the nation do away with it?

All of the researchers interviewed for this story were asked this question.

Not one of them was willing to say yes.

"I've recommended my neighbor take the GED, I've recommended my friend's daughter take the GED," says Lois Quinn at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. "I recommend it to anybody because it's a piece of paper. But as an alternative to high school? It's just selling a huge portion of the population short."

Critics of the GED say it was never anyone's intention to sell dropouts short.

"I don't think anyone [was] going out and saying we're going to try to pull a fast one on these people," says Heckman. But he says the GED is not a good solution to the nation's dropout problem.

"I think the first thing to do is just have everybody at every level understand what the GED measures and doesn't measure."

— Researcher Tim Kautz

The ideal solution is to get students to finish high school. But there will always be kids who quit -- and then there are the 39 million Americans who have already dropped out.

It's not clear what would be better than the GED. Researcher Tim Kautz suggests a place to start:

"I think the first thing to do is just have everybody at every level understand what the GED measures and doesn't measure," he says. "So, policymakers realize they shouldn't just evaluate programs based on the GED. Teachers realize that it's not quite equivalent to a high school degree, so they shouldn't encourage their students to get it instead of finishing high school. And students realize that it's not equivalent to a high school degree either."

Researcher Janice Laurence at Temple University believes the GED holds on because, as a society, we need a solution to the problem of bad schools and kids who don't make it to graduation.

"I think it assuages our guilt if we say, 'Yeah, people fall through the cracks and they don't get a diploma. Ah, but here's your consolation prize. You can have a GED, so it's just as good,'" she says. "So we give somebody this credential and we think that, OK, well we're done. There's more that goes into it than a piece of paper with loops and curls on it. It takes time. And it takes a lot more than just a test."

The audio version of this documentary is available as an MP3 download and as a transcript. Explore some of the research on the GED here.

For more American RadioWorks documentaries, browse our education archive and subscribe to our weekly podcast. Follow the program on Twitter @AmRadioWorks.

|

Executive Editor and Producer: Stephen Smith Special thanks to Manda Lillie, Hans Buetow, Samara Freemark, Frankie Barnhill and Harry Backlund. Additional support for this program was provided by Josh and Ricka Kohnstamm and the staff at Kohnstamm Communications. Support for "Second-Chance Diploma" comes from Lumina Foundation, the Spencer Foundation, and The William and Flora Hewlett Foundation. A note of disclosure: Some of the research cited in this program was funded by foundations that support American RadioWorks. The foundations do not influence how ARW covers the issues. |