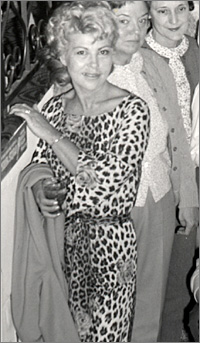

| Kitty Shenay, 1968

courtesy of Teresa Harrison | |

The Last Days of Kitty Shenay

part 1 2 3 4 5 6

Looking Back

By mid-February, five months after her diagnosis, Kitty's body shows mounting signs of failure. Her feet swell up. Her "bad days," those in which she's so tired she hardly rises from her bed, are coming more often. Her digestive problems are causing more stomach pain. The cancer has spread from her pancreas to her liver.

The circle around Kitty has closed. She rarely leaves the apartment. Besides Roland, her hospice nurse, her only visitors are close family.

One day Kitty's eldest daughter, Teresa Harrison, sits on the couch with Kitty, an old photo album open across their laps. The pictures are from the 1960s and '70s, when Kitty ran a hair salon in Myrtle Beach.

"Isn't that a bouffant, is that what you call that?" Teresa teases.

"Whatever was in, you had to go with it on," Kitty says defensively.

"My mother was very foxy," Teresa tells a visitor. "You should see these pictures. Oh my God, you're 'My Dream of Jeanie' or something!"

Kitty says she's loved her life, but it was hard. Growing up near Fort Bragg, the Army post in Fayetteville, North Carolina, she married a soldier at age fifteen to escape her alcoholic mother, she says. Some of her biggest dreams were out of reach.

"I always wanted to be a dancer. Or a secretary, that was the two things I really wanted. Back in those days we didn't have much choice."

Kitty moved a lot with her husband, an Army officer. After raising four children, they divorced and Kitty later married her current husband, Maurice Shenay. Her biggest blows were the loss of two adult children - a son in a plane crash and a daughter to lupus.

Teresa says her mother's stoical response to terminal illness is typical of her. "Mom won't let us know, she doesn't want people to know, that she can't handle something. People have to understand that she's on top of it, no matter what she's going through. Otherwise it's a weakness."

Kitty nods in agreement. "Because I always had to be strong."

The hard news keeps coming. Kitty gets word that her sister, who lives in Virginia, is gravely ill. Kitty's hospice nurse, Roland, makes his weekly visit as Kitty plans to see her sister one last time.

"You must be sad," Roland says, "to think of...."

"Yes," Kitty says, "but it's better to see her alive than dead."

Since the subject of death has come up, Roland turns the talk to Kitty's future.

"You haven't seemed very scared of ... of dying," he says.

Kitty replies that she doesn't want to die, "but, you know, I don't have any choice."

Asked about his reminders to Kitty that her decline is inevitable and imminent, Roland says he offers them "as gently as possible," but with a purpose. Terminally ill patients have a natural tendency to get complacent, to think that since they're feeling well on a given day that that will continue, Roland says. Or patients and their families may "freeze" in fear, lock themselves up emotionally, in the face of life's ultimate challenge.

"I think it's helpful for families and patients, not to be continually reminded of their dying, but to not lose sight of those things that are of value in the here and now. Each day is such a unique opportunity for folks to engage with each other in such a real and unalloyed way."

And, he adds, to review one's life, to reflect on it, and, ideally, to find meaning in it.

Next - Layering Back Who We Are

|