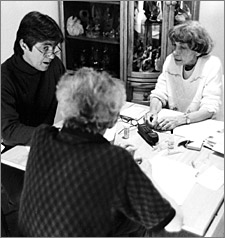

| Kitty and Maurice talk with Roland Siverson

photo by Tom Rankin, Director of the Center for Documentary Studies | |

The Last Days of Kitty Shenay

part 1 2 3 4 5 6

An Uneasy Decision

When she was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer in the fall of 2003, Kitty Shenay's doctor estimated she'd die within six months. That's what's required to trigger payments for hospice under Medicare, a six-months-or-less prognosis.

"I'm gonna tell you something," Kitty says, recalling what it felt like to get the news. "You know, you think about people on death row? That was my first thought - I'm just like those people. I'm on death row."

Kitty became a patient of UNC Hospice, a branch of the University of North Carolina health system. Her hospice nurse, Roland Siverson, visits her about once a week at the townhouse in Durham where Kitty lives with her husband.

Roland is a youthful 52-year-old, a one-time carpenter turned nurse in middle age. He has kind eyes and a teenager's head of brown hair. He enters the apartment with a smile and a warm, "How are y'all doing?"

"I really feel good," says Kitty.

"You look great."

Kitty has done better than expected, given her large tumor. She and some family members took a cruise in the fall, then spent a Christmas vacation at the beach. She and her husband, Maurice, are still managing their lives, with regular visits from Kitty's daughters. The cancer's progression has been gradual but unmistakable. She and Roland discuss her medications: the Fentanyl patch to control pain, Reglan for digestion, Fenergan for nausea. Roland checks her blood pressure and heartbeat and listens to her lungs.

Roland stays for a full hour. He and Kitty chat like friends about Kitty's children and her family history. Then the talk turns to Maurice's health. Kitty's 90-year-old husband has a batch of illnesses that may soon make him a hospice patient, too: lung cancer, emphysema, and asthma.

"Are you feeling relatively stable?" Roland asks Maurice.

"Yeah, I feel pretty good. Just very tired, I have no energy."

"He sleeps all the time," Kitty whispers in an aside.

Hospice tries to ease the sometimes-dreadful realities of terminal illness, but it can't erase them. In talking with Kitty and her family, Roland mixes optimism with gentle frankness. When Kitty laments her faltering digestive system, and the realization that she's "never going to have a piece of bacon again" because of the discomfort caused by greasy foods, Roland nods empathetically before delivering a reality check. "You've been doing so well for a good long period of time now," he says, "but there will be, invariably, some changes."

"I know, I know," Kitty says. "You don't have to tell me. It's not uphill, it's downhill."

Perhaps with this kind of exchange in mind, Kitty's daughters had doubts about calling in hospice when Kitty was first diagnosed.

"We weren't really sure we were so ready for mom to go in hospice," recalls her older daughter, Teresa, who visits often from her home three hours away in Spartanburg, South Carolina. At the time, Teresa says, she wanted Kitty to fight the cancer somehow, perhaps to try an experimental diet Teresa had read about online. And she wondered if Kitty shouldn't wait until death was closer before starting hospice care.

"I think I felt that them coming in early was like a constant reminder.... Every time they walk in the door, it's a reminder that [you're] dying."

Kitty shrugs off that worry. "I don't think I've ever felt like that." But Kitty had her own doubts when her doctor first brought up hospice. "My reaction wasn't favorable because I didn't know that much about hospice."

Kitty imagined group sessions with other terminally ill patients, she says, and having hospice volunteers "sit with you through your pain."

In fact, volunteers often play a key role in hospice care, spelling family care-givers, offering friendship and conversation, running errands as needed. Kitty has not felt the need to take advantage of hospice volunteers. For her, hospice has meant a particularly helpful brand of medical care. Like Kitty, most hospice patients are cared for at home.

"You have someone here once a week to take all your vital signs." She remembers older relatives, frail with cancer, forced to travel for weekly visits at the doctor's office. "And sometimes that person would be hardly able to get in a car! So this is just wonderful. This way I don't have to ask someone to drop by the drug store for me. They deliver it for me."

Next - Looking Back

|