|

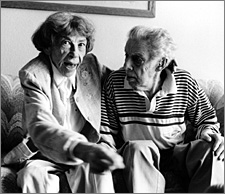

| Kitty Shenay with husband Maurice Shenay

photo by Tom Rankin, Director of the Center for Documentary Studies |

|

View a slideshow of the last six weeks of Mary "Kitty" Shenay's life |

|

The Last Days of Kitty Shenay

part 1 2 3 4 5 6

The family matron walks gingerly as she arrives for a gathering in her honor on a mild January day. Stepping out of a large sedan in front of her granddaughter's house on a cul-de-sac in Fayetteville, North Carolina, the elderly woman is greeted in the driveway by several relatives, then gets a hug from her granddaughter on the front steps of the modest house.

"Hi, Nanny."

"Hi, Sweetie," says the frail 78-year-old in a strong but slightly shaky voice. Surrounded by several grandchildren, a son-in-law and a couple of great-grandchildren, she steps through the screen door and into the kitchen.

She was born in October, 1925. Her name is Mary Katherine Shenay but everybody calls her Kitty. She used to be plump and rosy-cheeked, the owner and operator of beauty shops in Myrtle Beach, South Carolina. Now she weighs just 90 pounds and jaundice has given her face a yellow pallor. But her gaze is sharp, and she's still in command when she wants to be, for example, giving her granddaughter, Sita, tips on how to get the gravy and the green beans just right.

She's the center of the family, says Donna LeFebvre of Chapel Hill, one of Kitty's two daughters. "She's the kind of grandmother that was always on the floor playing with your kids. She's the kind of mother, and grandmother, that if you know something's wrong you can go to her. So when she was diagnosed it was pretty devastating for the family."

Four months ago, in the fall of 2003, doctors discovered a large, cancerous tumor, "advanced stages," in Kitty's pancreas. The tumor was too big, and it was too late. That's where hospice starts - with a decision to stop fighting for a cure.

"My doctor, David Goldstein, when he was talking to me and my daughters, suggested that I go to hospice because it was nothing that could be done," Kitty explains. "And I am so glad he did. Because I have seen where chemo has made people sicker than the ailment that they had, and they died anyway. My mother had radiation and it really burned her up. So I have had a productive life rather than be sick with my hair coming out and everything."

In other words, that even though cancer is killing Kitty, she's not dying today, or spending her energy fighting for life. She's living. And, little by little, letting go.

"That's the hardest thing," Kitty says, sitting at a small table in her granddaughter's kitchen while the meal preparation happens around her. "When my kids were coming home, I'd always have the meals planned. So at Christmas time I had to turn everything over to them. Only two things, I made the dressing and the coleslaw. And I thought, 'Oh my God, it's going to be so hard on them, they won't be able to....' But they did the greatest job. You would not have believed that table. So I knew right then I didn't need to be in the kitchen anymore."

"Nobody can make your coleslaw, Mom," says Kitty's daughter, Teresa Harrison, from her spot near the stove.

"Or pound cake," adds granddaughter Sita. "Or stuffing."

Kitty smiles wistfully at the compliments. Then she says, matter-of-factly, "You will the next time."

Next - An Uneasy Decision

|