|

In recent years Charlotte schools have become more segregated. Students now wonder what they're missing with less school diversity. But one mom says schools forgot about education in the pursuit of racial mixing.

Students at Providence High School

Students at Providence High School in Charlotte, (from left) Navid Nematollahi, Amber Koonce and Michelle Belsante. Photo by Catherine Winter The American South has had the most integrated schools in the country for decades. But a new study says it's rapidly losing that distinction.

The report from the Civil Rights Project at UCLA says many schools are becoming more segregated. One reason is that there's a smaller percentage of white children in public schools overall. But the report says another factor is public policy.

Communities around the country have stopped busing children to integrate schools.

In Charlotte, NC, a judge threw out the school district's busing plan in 1999. Most students in Mecklenburg County now go to neighborhood schools. That means schools aren't nearly as integrated as they once were.

Providence High is in a wealthy Charlotte suburb. It used to be quite mixed. Now, more than 80 percent of the students are white. But student Navid Nematollahi says there's still diversity at Providence.

"When we have our pep rallies here, one of the highlights is the step team, and everyone loves it," he says. "It's African American. People prefer that to the cheerleaders because it's something different. We have our Asian dinner and multicultural club, and people appreciate that."

Navid co-chairs the Diversity Council at Providence with classmate Michelle Belsante. Michelle says even though Providence is mostly white, it's possible to learn about other cultures.

"I make sure to socialize with people who are not just Caucasian," she says. "I'm friends with people who are of all different races. I mean Asian, African American, all different races. It just, it depends on how you put yourself out there, and with the Diversity Council I have learned to make friends with people who are very diverse."

Still, classmate Amber Koonce says she wishes there were more people of color in her classes.

"Our summer reading book was Invisible Man, which was about a black man and he joined the Black Panther movement," she says. "It had a lot of deep underlying themes about it. But we couldn't really talk about it or go into detail with it because, well, I am the only African American in my English class."

Amber says she'd like to have people of other races in her history class, too, especially when the class is talking about issues such as slavery or the Holocaust.

"I think the problem is we don't know any different than the environment we are in, so we don't know what we're missing out on," she says. "I could be missing out on a lot of stuff, and I wouldn't know just because I haven't been given the opportunity to have the experience."

West Charlotte High School

The "Mighty Lion" of West Charlotte High School.

Photo by Kate Ellis West Charlotte High School, once known as the crown jewel of Charlotte's desegregated school system, now has very few white students. A lot of the students are poor and struggle with low test scores.

Still, West Charlotte has its share of high achievers. As they plow through advanced placement courses and demanding extra-curricular programs, these students have their eyes on a world that will reach well beyond the walls of West Charlotte. As they see it, finding diversity outside school is crucial to preparing for opportunities that lie ahead.

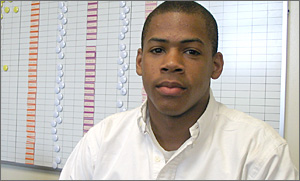

Isaiah Scott was senior class president at West Charlotte High School in 2007.

Photo by Kate Ellis "In the world it's not one race," says Isaiah Scott, 2007 senior class president. "My boss isn't necessarily going to be my same skin color. They're not going to have the same views I do. One of my friends is Hmong. You don't meet too many Hmongs! But he told me about his culture and his religion and how they marry. If I ever meet another Hmong I can speak to them. I know kind of how they are."

Before race-based busing ended in Charlotte, Scott attended racially mixed schools. He intends to attend Morehouse College, a historically black school. Still, Scott prizes the inter-racial experiences he had coming up through Charlotte's public school system. "It's going to be a huge advantage if I go on an interview with someone of another race," he says. "They aren't going to intimidate me. If I had grown up around African Americans my entire life, I might not have had that same advantage."

Maria Suarez hopes to dispel stereotypes about Latin American students by excelling at West Charlotte High School. Photo by Kate Ellis Maria Suarez is Colombian and finds herself a minority in this largely African American school. Her parents were doctors in Colombia and Maria is eager to excel in the United States. She wants to do well not just for her parents' sake, but to dispel myths about Latin Americans that she hears in school.

"Hispanics are thought of as not being into academics," she says. "I want to prove the stereotype wrong."

Suarez has found some of her classmates frustratingly naïve about her background. "I know a lot of people who have never experienced diversity at all," she says. "They call me Mexican. I try to teach people about Latin American cultures, especially at West Charlotte. It's sad to see that - I mean, you say 'I'm from Colombia,' and they say, 'Oh, what part of Mexico is that'?"

Patrick Jones stands outside the church where he plays saxophone during Sunday services.

Photo by Kate Ellis Patrick Jones takes advanced courses, plays athletics and studies music. Some of his most interesting exposure to people from other backgrounds comes from playing in a band.

"I'm in a saxophone group with two Russian brothers," Jones says. "At first it seemed as though they didn't know how to approach me because I'm African American. But now we know each other."

The group comprises five teenage boys, two Russians and three African Americans. "We call them the Russian Brothers and they just call us the Brothers," he says. "They don't have to change who they are and we don't have to change who we are, because we're around each other all the time. I know what they like. They know what I don't like. It's as though we're all one family."

Jones says that's the way life ought to be. He feels for peers that seem only comfortable with people from one group. "I know lots of folks who have only known their family and people like them," he says. "Lots of things they say are ignorant, and you say, 'Wake up and see the world for what it really is.' You try to get them to understand that it's more than what they see in the media. You have to go out there and meet somebody."

Sharon Starks

Sharon Starks writes about education issues in Charlotte. Photo by Kate Ellis Sharon Starks moved to Charlotte from Kansas when her three children were in elementary school. "We thought it would be easy to move to Charlotte," she says. "I came in thinking it would be like any place else and it wasn't. It involved busing." Starks immediately missed the neighborhood camaraderie she had enjoyed in other cities. In Charlotte, "everybody was going to different schools," she says.

Starks says busing was much more feasible in Charlotte 20 years ago, "but we've more than doubled the population since then." Starks believes there are just too many people now in Charlotte-Mecklenburg County to make busing work. "You've got to have connections to make people feel like a part of a school," she says. "We've lost that."

As Starks' children got older she began writing editorials for the Charlotte Observer, including ones that criticized the city's busing plan. Eventually she was invited to join a task force to work on challenges facing Charlotte schools.

Starks was glad when race-based busing ended in Charlotte in 1999. But she bristles when critics say it led to resegregation. "That sounds deliberate to me," she says, "like white parents don't want their children to go to schools with kids who are different from them."

Starks says opposition to busing in Charlotte now isn't about race. It's about devising a school system that meets the needs of broadly different students. "For African American kids," she says, "there was a huge achievement gap, and it didn't change [with busing]. People were so focused on diversity that no one was focused on education. It was almost impossible for there to be equity because kids weren't coming in equitably. The schools were giving everyone the same education when everyone has different needs."

For Starks, one way to begin offering a better education to all of Charlotte's students is to return to neighborhood schools. "So I don't look at it as resegregating," she says. "I look at it as reconnecting."

Back to An Imperfect Revolution

|