|

The Circuitry of Fear

Listen

Twenty people gather around a conference room table in midtown, Manhattan. Though it's been years since the World Trade Center attacks, the people in this room are still suffering. The facilitator asks people to go around the room and give their name, and describe whether they are in pain. "I'm Barbara Williams and I'm in pain physically and financially," says one woman. "I'm Bert and I'm in pain," says a man. "Oxsana, too much pain" whispers another woman.

Pain, physical and mental, is what this Red Cross support group is supposed to help with. All of the people here are living with psychological wounds from 9/11.

| "I'm Clarence and I always feel sad," says a muscular man in a denim work shirt.

Clarence Singleton is a retired fire lieutenant who pulled people from the debris at ground zero on 9/11. Singleton dislocated his shoulder that day, but it wasn't just the physical injury that caused his life to unravel.

"I remember I couldn't get out of bed in the mornings and I wasn't cleaning the house, and I don't complete anything. Like, I used to paint and play guitar. Now I only pick it up sporadically. I just don't continue anything, which is different than the way I was before," says Singleton.

In the immediate aftermath of a disaster, it's normal to be distressed. Many people have difficulty sleeping and concentrating. Some have nightmares. |

|

Retired NYC fire lieutenant Clarence Singleton was injured doing rescue work on 9/11. © Klaus Reisigner/Editing-Server

|

What's different about people who develop post-traumatic stress disorder is their symptoms don't get much better over time. Dr. Sandro Galea, an epidemiologist with the New York Academy of Medicine, did a phone survey in Manhattan five weeks after the September 2001 attacks. Many New Yorkers in the survey said they were reliving the event.

"So, in the case of 9/11," says Galea, "it means you start imagining and thinking about the towers falling over and over again. You have avoidance, which means you try to avoid things that remind you of the event. So you don't want to go into tall buildings, or you avoid flying on planes. And you have intrusion, memories and symptoms that keep bothering you. And you also have arousal where you're jumpy, and easily irritated and unhappy."

Doctors don't diagnose post-traumatic stress disorder until at least a month has passed since the traumatic event. More than a month after 9/11, Galea's survey found 7.5 percent of Manhattanites had enough symptoms to suggest they might have PTSD. At six months, fewer than one percent had the symptoms. Most people got better. The question that interests researchers is why some people didn't.

Patients at Silbersweig's Neuroimaging lab at Cornell University Weill Medical College view a slideshow containing 9/11 images while researchers measure changes in blood oxygenation. Photo: Stephen Smith.

|

|

In a brain scanning lab at Weill Medical College at Cornell University, Dr. David Silbersweig is studying the circuitry of fear in the brains of people with PTSD from 9/11.

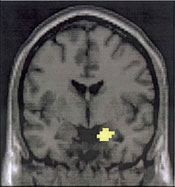

A patient lies inside an MRI machine and watches a slideshow. Some pictures are serene, like a picnic or a vacation photo. Others are scary, like the World Trade towers burning. As the patient watches the images, the scanner measures the changing levels of blood oxygen flowing to parts of the brain that control emotions. On a monitor, bright yellow patches in a part of the brain called the amygdala show where the brain is especially busy

"We can pinpoint precisely where the activations or abnormal activations are taking place," explains Silbersweig.

When asked if people who are suffering more show brighter activity in these areas, Silbersweig confirms."That is exactly what this shows." In fact, this is a correlation between clinical severity and the degree to which there is increased activity in this core fear related structure." |

|

In all animals, both fear and the memory of frightening events are essential for survival. But researchers say that in people with PTSD, the fear system seems to get stuck in the "red alert" position.

Silbersweig says it's not clear whether trauma alters the brain, or whether people who have PTSD were somehow more vulnerable to trauma in the first place. "The jury is still out," he says, "and it may well be that both are the case."

|

|

This diagram shows increased flow of oxygen to the amygdala while patients are in the presence of a traumatic stimuli. Photo courtesy of David Silbersweig.

|

Continue to Part 2

|