|

The Circuitry of Fear

Researchers say a person who has been traumatized before is more likely to develop PTSD after a new event. Singleton, the firefighter injured on 9/11, felt the cumulative weight of his traumatic experiences. "I had post-traumatic stress already from Vietnam, but I was unaware of it, and after 9/11, it got worse. And I still didn't know what was happening to me, so I checked into the VA hospital. Sometimes I wonder, and I always get sad talking about this, but sometimes I wonder if there is any hope," says Singleton.

Difede's virtual reality therapy allows patients to revisit the events of 9/11 at their own pace. Photo: Dr. Hunter Hoffman at the University of Washington.

|

|

Mental health experts say there is hope. A drug called propranolol may blunt the formation of traumatic memories if it's used right after the trauma. Anti-depressants and anti-anxiety medications can ease some of the symptoms of the disorder. But the most tested treatment for PTSD is cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT).

Psychologist Joann Difede directs the Anxiety and Traumatic Stress Program at Cornell University. She says CBT leads a patient back through the traumatic memory to organize the disturbing fragments into a coherent story. "They gain a sense of mastering control over their experience," she explains. "And it's not terrifying in the present anymore. They can distinguish, it's a memory now, it's not happening again."

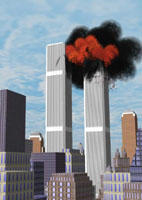

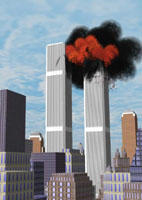

But Difede says some people with PTSD may not be able to recall the details of the trauma, at least not well enough to put it to rest, so she's experimenting with a virtual reality therapy. Difede's patients pull on a set of goggles and find themselves in New York City. Difede narrates as the images change on screen, "It's the World Trade Center as it might have been on September 11. Clear, crisp blue skies like any September day. And then the next step would be you'd see the plane fly overhead, a commercial airliner."

There is a crash, then the sound of screams and sirens. |

The sound and images get more intense and build from plane crash, to explosion, to the horrific site of people jumping to their deaths and the towers collapsing. Difede talks the patients through what they're seeing. The idea is to get them to confront memories they've been afraid of, and then to organize the thoughts into a less debilitating story.

| One of Difede's patients after 9/11 was Long Island Fire Chief Stephen King.

Sitting on his front porch waving goodbye to his granddaughter, King's a burly guy who still wears a New York Fire Department shirt, although he's now retired. King says on September 11, he got a career's worth of trauma in one day. The fire chief was used to being in control of dangerous situations, but after 9/11 he felt overwhelmed by new fears. He used to love to go to Broadway shows, but stayed home because he was afraid to cross the Brooklyn Bridge.

King remembers, "I felt vulnerable. You know, like somewhere out of the sky a plane was going to come and hit that bridge or whatever." |

|

Retired Chief Stephen King at his home in Long Island. Photo: Sasha Aslanian

|

Psychologist Joann Difede. Photo: Weill Cornell Medical College.

|

|

A year and a half of talk therapy and anti-anxiety medication helped him make it across the bridge, but there were still disturbing blank spots in his memory. Difede suggested he try the experimental virtual reality goggles. King was skeptical.

"When I first watched it, I thought, 'How could this possibly help me?' But the reality is that as I watched it, she had me again talk about my experiences. You know, 'Did you see the buildings when it looked like this? Where were you then? What do you remember about that?' etc. You watch a plane hit the North Tower.' Where were you?' And the net result is it allowed us to continue on. It really did work," says King.

King says he feels better, thanks to the therapy, but he's still not back to normal. Difede says that's to be expected. "The very nature of going through a terrifying life event is going to change a person. What the treatment does is it cures the PTSD, if you will it treats the symptoms, but it doesn't address the existential issues that a lot of people are left with, 'How should I live my life? What's meaningful? Am I living my life the way I want to live it?'"

Difede says no therapy can give patients back the lives they had before September 11. |

Back to: Trauma and the Brain

|