|

|

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

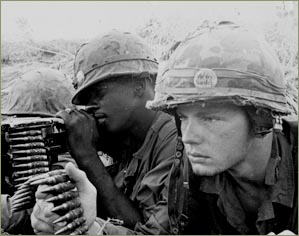

Wisecracks aside, Lyndon Johnson was pessimistic about Vietnam. His military advisors were urging him to bomb the North Vietnamese capitol, Hanoi, a move that might provoke the Chinese. Senate Majority Leader Mike Mansfield, a Democrat from Montana, advised against bombing. Mansfield also opposed sending in more American troops. As he had with Senator Russell, the president expressed his own concerns about the Pentagon's need for more men. The two spoke on the afternoon of July 27, 1965.

Opinion polls in spring of 1965, showed Americans favoring military action in Vietnam two to one. But Johnson knew that support would erode if expanded fighting sent more Americans home in body bags. In a June 21, 1965, call with Defense Secretary Robert McNamara, Johnson described with almost stunning prescience how the future might - and in fact, would - unfold, with domestic opposition growing to a distant war the U.S. did not know how to win.

Despite his doubts, the president plunged ahead. By the end of 1965 Johnson had authorized 175,000 American soldiers to Vietnam. By 1968, that number had grown to half a million. As the war dragged on, and the American death toll steadily grew, so did a massive anti-war movement. Historian Michael Hunt says that to listen to Lyndon Johnson's phone calls on Vietnam is to hear a man making a decision that will tear up his country and cripple his presidency. "The youth protests [chanting] 'Johnson's a war criminal,' that was personally devastating for him," Hunt says. "And the fact that he couldn't go out and shake hands and mix with people, that became more difficult as protests became more common and more vociferous. His people! He'd done so much for them, and they were turning against him." The Vietnam War killed 58-thousand Americans and more than a million Vietnamese. Johnson's presidency was consumed by Vietnam -- and in 1968, Lyndon Johnson announced he would not run for reelection.

Next: Back to Johnson | ||||