|

|

|

|

|

|

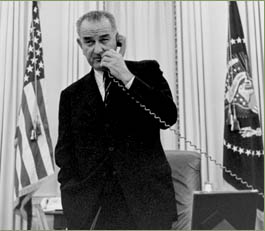

The Sudden President |

|

|

Few presidents have had to lead a nation out of the kind of dark turmoil caused by JFK's assassination. Lyndon Johnson used the telephone to navigate his first tumultuous months as president. A veteran of Washington politics, LBJ called on both friends and rivals to pull the country together.

|

|

|

|

|

The Road from Selma |

|

|

When Lyndon Johnson became president in 1963, white liberals and African Americans feared the Southern leader would weaken JFK's civil rights agenda. Instead, Johnson capitalized on Kennedy's legacy to pass the landmark 1964 Civil Rights Act. In 1965, he used a brewing racial crisis in Selma, Alabama to go even further.

|

|

|

|

|

The Vietnam Dilemma |

|

|

Critics have long accused Lyndon Johnson of mindlessly plunging into the Vietnam War. LBJ's phone tapes complicate this view. Johnson refused to be the man to lose the war in Vietnam, but he had grave doubts about how he could win it.

|

|

|

|

|

Jackie Kennedy and LBJ in the Days After |

|

| Shortly after assuming the Presidency, LBJ developed a surprisingly intimate relationship with the newly widowed Jackie Kennedy. |

|

|

The Sudden First Lady |

|

| Lady Bird Johnson kept an audio diary during the full five years she spent as First Lady in the White House. Mrs. Johnson's first entries vividly recount her memories of John F. Kennedy's assassination and her husband's sudden transition to president. |

|

|

|

If there were one single tool of Lyndon B. Johnson's presidency, it was the telephone. "As president, Lyndon Johnson used the telephone like an assault weapon," writes historian William Doyle. "He didn't just pick up the telephone, he grabbed the telephone," a witness to Johnson's phone style said. Former aides recall Johnson practically crawling through the wire to bully, cajole, and persuade people.

During the first, frenzied years of his presidency, Johnson easily made 40 calls a day. Seldom a time-waster, LBJ would sometimes have three calls going at the same time. After his first full day as president - before he even moved into the White House - Johnson ordered Kennedy's phone system overhauled so he could reach people more quickly. Doyle reports that phones were installed all over the Johnson White House: "under dinner tables, coffee tables, end tables, in bathrooms, and on windowsills." Johnson wired his Texas ranch, and - long before wireless phones became commonplace - had phones rigged up in cars and on boats. Columnist Joseph Kraft wrote, "He must be the only man in the world who has had a phone installed beside a hammock."

If LBJ made passionate use of the phone, he taped his calls with equal vigor. Johnson began recording his phone conversations within hours of becoming president. On the night he returned from Dallas on November 22, 1963, LBJ spent about three hours in his vice presidential office in the Executive Office Building. He already had a recording device attached to a phone there, and used it when he called Kennedy loyalists such as Supreme Court Justice Arthur Goldberg, and the treasurer of the Democratic National Committee, Richard Maguire. From that night to the last days of his presidency in 1969, Johnson recorded more than 9,000 of his conversations.

Johnson made his secretaries transcribe many of these calls and used the transcripts to keep track of daily work and decisions. Presidential historian Michael Beschloss writes that the demand on Johnson's secretaries was immense: "The secrecy, haste, and difficulty of the work made them nervous and they had other tasks to do. LBJ's secretary Yolanda Boozer recalled that during his early months in the White House, she often worked at night, when there was less chance that an outsider might discover what she was doing. Transcripts were slipped into the President's bedroom night reading."

Harry Middleton, who worked as a Johnson aide and as a director of the Johnson library, says the LBJ tapes reveal a man very few Americans knew. "He really, really, really wanted to sound and act presidential," Middleton told a 2003 conference on the White House tapes. "The presidential president was very formal and very stiff in many of his press conferences and public statements. One on one, to small groups, he was colorful, witty, funny, a marvelous character. And that's the way he was in the telephone tapes," Middleton says. He concludes, "Whatever value the Johnson tapes will be said to have for history, one virtue of them is they bring to life a man who would not otherwise be known to the public that he served."

|