The Eighth Wonder of the World

part 1, 2

The Pacific Northwest is known for its lush, rainy coastline. But if you drive east, over the Cascade Mountains, you descend into desert. It's sand and dust and sagebrush. The wind pushes tumbleweeds across the road. It's always windy.

And then suddenly, in the midst of all this dusty brown, there will be a wide field of velvety green plants, or an orchard of fruit trees.

One of these green patches of earth belongs to Mick Qualls. His farm, like all the other farms in this region, depends on irrigation.

Canals carry water from the Columbia River to farmers' fields.

Photo by Catherine Winter

"We wouldn't be here if it wasn't for our water," he says. "This is really the most harsh desert in the United States."

This part of Washington, a few hours east of Seattle, gets just a few inches of rain a year, less than Death Valley. But it's a tremendously productive growing region, putting out apples, cherries, corn, alfalfa, vegetables, mint, and mountains of potatoes.

Qualls keeps a satellite map posted on the walls of his office. The map shows rows and rows of green circles. "These circles are all sprinklers," he says. Each sprinkler irrigates 125 acres of farmland.

Qualls traces the snaking line of the Columbia River, through the desert and up to where it suddenly broadens out into an enormous lake.

"Right there, you can see, this is the Grand Coulee Dam," he says. The dam is an hour and a half to the north, but it diverts water from the river to Qualls's farm via a complex series of canals, pipes, and siphons. Water diverted by the Grand Coulee Dam irrigates 600,000 acres of land.

"If something happened to that dam today, this would all go right back to desert," says Qualls.

But because there is a dam, there are farms, and the industry to support them. Qualls runs a lab to test pesticides. And there are other farm-related businesses here, such as potato processing plants that make French fries for fast food restaurants. Those plants use potatoes grown on the farms, and they use electricity generated by hydropower dams on the area's rivers. The biggest of those dams is Grand Coulee.

Building the Dam

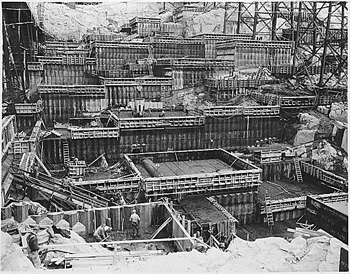

The construction of a group of concrete blocks near the east end of the Grand Coulee Dam. April 1, 1937

National Archives

During his 1932 campaign, Franklin Delano Roosevelt courted voters in the Pacific Northwest, and he promised dams. At the time, the Northwest depended on mining, lumber, and farming. It was an economy based on raw materials, not manufacturing, and it was hit particularly hard by the Depression. Unemployment was even higher in the Northwest than in the rest of the country.

As soon as Roosevelt took office, local politicians and businessmen began to pressure him to keep his promise to build dams. The Grand Coulee Dam became his administration's largest public works project. When it was complete, it was the biggest thing human beings had ever built, anywhere.

The plan was to build a concrete structure more than three-quarters of a mile long and 550 feet high across the Columbia River. The site was wide, dusty desert land with no town nearby, beautiful, forbidding country, with high rock ledges surrounding broad valleys called coulees.

Even though the area was largely uninhabited, films and photographs show huge crowds greeting President Roosevelt when he made visits to the site. People must have traveled hours through the desert to get a glimpse of him. When Eleanor Roosevelt saw the site, she reportedly said it must have been a good salesman who sold that dam to Franklin.

She was not the only skeptic. Others wondered why it made sense to bring electricity to a region where no one lived, and irrigation water to an area where hardly anyone farmed. The Army Corps of Engineers recommended the dam not be built, because there were not enough people and industry to use its electricity. But others within the government thought the need for electricity would grow.

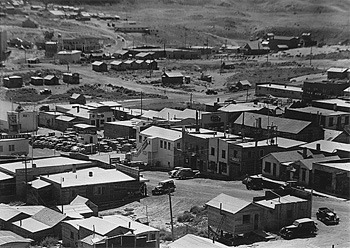

Grand Coulee, Wash., a boom town near the constuction site of the dam. September 1935.

National Archives

Roosevelt believed the dam would help develop the Northwest. When he visited in 1934, the Associated Press quoted him saying, "We are going to see, I believe, with our own eyes, electricity and power made so cheap that they will become a standard article of use, not only for agriculture and manufacturing, but also for every home within reach of an electric light line."

As construction began, towns sprang up around the site. People came from all over the United States and Canada, hoping for jobs. The project employed tens of thousands of people. So many workers put in so many hours that the dam was finished two years ahead of schedule, in March of 1941.

Continue to part 2, back to PWA, or return to Bridge to Somewhere.