|

Part: 1, 2, 3

Energy Crisis Redux

The idea of getting fuel from aquatic plants has existed for decades. But it seems to take an emergency to push America away from petroleum. A generation ago, the United States was facing another energy crisis brought on by the OPEC oil embargo. Oil prices quadrupled. The federal government sought to counter the OPEC cartel and solve wrenching energy shortages. The most ambitious effort to tackle the crisis was announced by Jimmy Carter in 1979.

"The energy crisis is real. It is worldwide. It is a clear and present danger to our nation," Carter said in a major televised address.

Carter outlined plans to cut oil imports and boost domestic production and energy conservation. He also charted a third path. Today we call it "green energy."

"To give us energy security," Carter said, "I am asking for the most massive peacetime commitment of funds and resources in our nation's history to develop America's own alternative sources of fuel."

President Carter invested millions in new government research centers like NREL, the National Renewable Energy Laboratory in Golden, Colo. As part of NREL's Aquatic Species Program, researchers spent 20 years studying micro-organisms like algae. They were startled by algae's capacity to produce oil.

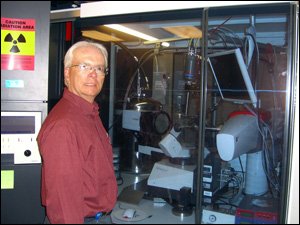

Al Darzins, a senior manager at the National Renewable Energy Laboratory in Golden, Colorado.

"It's amazing," says Al Darzins, a senior manager at NREL.

Given the right conditions, Darzins says algae could double its volume overnight. And unlike other sources, such as soy or corn, algae can be harvested day after day.

"If you could actually generate an algae strain that produces lots of oil, you could use this oil for a variety of bio-fuels," Darzins says. Including "fuel for ships and trains, jet fuel and even green gasoline."

"There is no other resource that comes even close in magnitude to the potential for making oil," says John Sheehan, an NREL energy analyst who worked in the aquatic species program. One of algae's great strengths, Sheehan recently told the journal Popular Mechanics, is its ability to grow robustly in brackish water. NREL's research initially focused on identifying natural algal strains that were then tested in outdoor pools in New Mexico, where much of the groundwater is saline and unsuitable for other forms of agriculture.

The government's alternative energy initiative was strong while oil prices stayed high. But in the early 1990s, the cost of crude oil plunged. So did interest in alternative fuels that were not cost-effective against petroleum. In 1996 the Department of Energy shut down the aquatic species program.

But just before work stopped, NREL researchers made an important breakthrough. Using new techniques, the scientists discovered it might be possible to boost algae's capacity to produce oil through genetic engineering. While NREL didn't actually produce oil from these strains, the work provided a road map for others to follow.

"Before then, people really had not been able to do any genetic transformation, that is the introduction of new genetic material into these organisms," Al Darzins says. "NREL at the time found methods of getting foreign genes into some of the strains they were working with. That serves as the basis for what a lot of people are going to be doing in the future."

Today, NREL is hoping to create new algae strains through genetic engineering, as part of an ambitious collaboration with private companies. Aurora's Matt Caspari will be watching closely. A lot of his company's work is based on the government's pioneering research.

The Heat of Competition

Flush with investment funding, Aurora moves its team and fish tanks into spacious, glass-enclosed offices in an industrial park perched on the east side of the San Francisco Bay.

But as the company prepares to hire more staff and step up operations, competition moves in on its home turf. A number of other small California start-ups announce plans to gear up algae-to-bio-fuel programs. Then oil giant British Petroleum announces it will invest $500 million in an alternative energy research center on the U.C. Berkeley campus. Elsewhere, Boeing, Virgin Atlantic and the Department of Defense also say they are studying ways to produce fuel from algae and other plants. It was daunting competition for three guys and their fish tanks.

As he reviews his company's successful launch, Matt Caspari spies storm clouds on the horizon.

"I'm not just worried about little start-ups," he tells us. "I'm worried about big companies too, because they can pour potentially as much or more money into an idea and put a lot of smart people to work on it. And the one advantage you have over a big company as a small entrepreneurial start-up is you can move really fast and make decisions really quickly. So, I feel a huge pressure to get results."

Aurora's chief investor James Horn says results may not be around the corner, but that's part of the adventure for early-stage venture capital firms.

"Aurora was a very raw company at the first conversation," he says. "It was effectively three guys with a plan on how to create a new energy supply for a growing world. But it was not a stretch to think that we could adapt algae to produce bio-diesel. So we made the investment. And it may take longer than we expect, but we're risk-takers by nature and we believe there is a chance to be successful here."

How do investors measure success in clean tech? It's clearly about making a profit. But for James Horn, saving the world from global warming is a welcome benefit.

"Using algae is effectively carbon neutral, it's not competing for food stocks, it's not competing for scarce water," Horn says. "In many ways, it is kind of the ultimate solution for powering our cars. You know, 18 months ago, I never thought I would be investing in an algae company."

Horn tells us Aurora's success depends on its secret, oil-boosting technology developed at Berkeley. Government scientist Al Darzins cautions that Aurora's claims seem impressive, at least on paper.

"But have they actually proven that?" he asks. "I suspect it's theoretical at this point and maybe [based on] some small-scale lab stuff that they've done and they extrapolate. But let's take that organism out of the lab and let's see what it does in the environment."

Scaling up lab experiments in large, outdoor settings is the biggest challenge facing Aurora and many other alternative energy pioneers.

"You're talking about hundreds or thousands of acres of algae growth," says CEO Matt Caspari. "So it's money and time to scale that up."

"They are trying to do something on a very large scale which hasn't been done before," says James Horn. "There are a number of hurdles that we haven't even addressed yet and that we won't be able to address until we can actually test it."

With more hurdles ahead, scientists are projecting it may take five years or more before fuel derived from algae is widely available. But one company in New Zealand is already marketing a new diesel blend. Five percent is from refined algae oil.

Alternative energy - whether from solar, wind or even algae - is no longer a tale of science fiction or distant dreams. That's obvious. Just look at the billions of dollars flowing into the market to back new, earth-friendly products such as green credits cards and bio-fuels. Investors insist intense competition in this green marketplace is no passing fad.

"Energy is the number one driver in the world," says James Horn. "And if we can migrate to alternative energy supplies, it can be an enormous industry both in California and worldwide."

Marianne Wu says, "It's a much more fundamental change that we're going through. So, it's not some little blip that it's hot today and tomorrow it's going to be some next hot thing."

The marketplace can deliver wealth of course, but it's hardly been eco-friendly up to now. More than 150 years ago, the California gold rush produced riches for some people, but environmental devastation and hardships for many others. And the gold rush wound down in just a few years. It will be up to contemporary consumers and eco-entrepreneurs and their shareholders to see that today's green rush evolves from an economic frenzy to a fundamental planet-saving change.

|