|

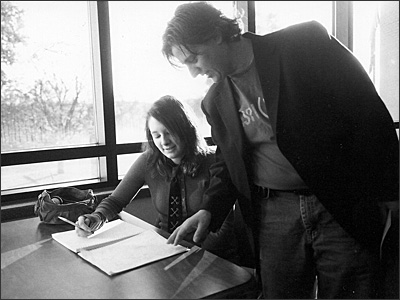

Michelle Chalmers has a passion for working with teenagers. She was a teenager herself when she went into foster care. Here, she talks with Kierstin about her artwork.

Photo by Stephen Smith

Michelle Chalmers spends her days trying to find families who will adopt teenagers, trying to persuade teenagers that they ought to consider being adopted, and trying to persuade the rest of the world that they should care what happens to kids in foster care.

She runs The Homecoming Project. It got a federal grant to try to prove that if you really make the effort, you can raise the adoption rate for teenagers.

She says she's well-suited to this work, because she knows what it's like not to have a family. Michelle Chalmers spent her teen years in foster care because her mother didn't want her.

"She would say the worst mistake of her life was having me, she should have aborted me because it was the beginning of the end of her life," Chalmers says.

Chalmers actually laughs when she talks about her mother. She laughs a lot. She talks a lot, too; she kind of fills a room. The kids she works with seem to like her. She's very funny. And she's very driven to do something to keep those kids from aging out of foster care and winding up on the streets.

When Chalmers herself turned 18 and couldn't stay in her foster home anymore, she went to college. That's unusual.

Young people who age out of foster care don't tend to fare very well. With nowhere else to go, many return to the biological families they were taken from to begin with, families where they faced abuse and neglect. They're more likely than their peers to end up pregnant, or in jail. One study found that one in five young people who age out of foster care becomes homeless.

Studies show that the longer kids stay in foster care, the better they tend to do. Some states allow young people to stay in foster care until they're 21, and those who do tend to fare better when they leave.

But in the great majority of states, young people age out when they're 18. Only about three percent of the young people who age out of foster care finish college. Many don't finish high school.

"I had a very smooth transition compared to any of the young people I work with now," Chalmers says. "I'm fortunate my IQ is all right. My mother didn't drink alcohol when she was pregnant. I don't have prenatal drug exposure. Those are strikes a lot of our kids have that I didn't have."

She was also driven enough to earn scholarships.

She remembers the day she arrived at college. Her foster dad drove her to campus, helped her carry in her boxes, and left.

"And my roommate is there with her parents, and they're unpacking her stuff and running off to Target to buy little trinkets," she says. "And I'm watching all of these kids and it is this huge exciting day for all these families. Their kids are going off to college and they're having parties and dinners … and I was just sort of plopped into my little dorm room with my stuff and, 'Okay, bye.' I mean he was there 15 minutes."

Chalmers hastens to add that her foster parents were nice people who took good care of her. She doesn't mean to complain about how she was dropped off at school.

"It's not the kind of thing that's earth-shattering," she says. "But it's those kind of small, significant things that drove home the point that these weren't my family. They gave me a place to be and took care of me, but when push came to shove I clearly wasn't their kid."

She couldn't go back and stay with that family in the summer. She had to find jobs that included housing, such as being a camp counselor.

She's gone on to make good friends and to find a partner, but she still misses having a family. She says she's 40 years old, but she's still aging out of foster care.

"Every holiday it's the same, trying to figure out how much time I can be with my partner's family," she says.

The people in her partner's family like each other. They call each other up to chat.

"It's very nice. It's very sweet," she says.

"It's wonderful but I have to take breaks. It makes my mind go crazy places … It's a constant reminder of what could have been, or what most people on the planet have, in terms of human relationships."

But that loss also helps her understand kids whose own families have fallen apart. "I think it's one of the ways that I think I do my work well, is that I know the empty spots," she says. "And that doesn't mean we're all a bunch of freaks running around who can't function. But I think there are vulnerable empty spots that are just going to be there."

So it makes her angry when people ask her why bother finding adoptive homes for teenagers.

"That blows me away, that anybody thinks that kids in foster care need families only until their 18th birthday," she says. "I say, you're 40, do you have a family? Most do."

Although many people lose family members to divorce and death, it's a rare person who has no family at all.

Chalmers says foster kids ought to have the same opportunity to have lifelong connections with people.

"We should have the same expectations for their future as the kids we birth," she says. "We have a higher responsibility to them because we took these kids from their families - for good reason most of the time, but implicit in that is a promise to find something else."

It makes her angry when well-meaning social workers teach foster kids how to find a homeless shelter or a food shelf after they age out.

"It's like people who go on suitcase drives to collect suitcases because foster kids often move with their stuff in a garbage bag. That just puts me over the edge. Why do we assume that it's OK for foster kids to move 500 times so we just get them luggage so they can do it prettier?

"People do these feel-good activities and the assumption is: You don't deserve a family, you're not going to get one … so here's a new duffel bag! Good luck to ya! It feels insane to me."

The project Chalmers runs, The Homecoming Project, got a federal grant to try to place more teenagers in permanent homes. It assigns kids adoption recruiters who search for people to adopt the kids. The project is now entering the fifth year of its five-year grant, and it has placed 30 kids in permanent homes. That's a third of its caseload, and a much higher rate than the state average.

Michelle Chalmers wants to keep doing this work. Once the grant expires, she plans to launch her own agency and keep finding teenagers a place they can call home forever.

Back to Wanted: Parents

|