Stephen Smith: From American Public Media, this is an American RadioWorks documentary.

Barack Obama: We are the Saudi Arabia of coal. We've got more coal than just about anybody else.

Coal has shaped America's history.

Barbara Freese: They saw all of this coal here as a gift from God … further evidence of our manifest destiny.

But coal's power came at a price.

Mary Janet Henry: There was always that sulfur smell in the air.

Joel Tarr: There were days when street lights had to be turned on at midday because smoke pollution was so heavy.

Today, city skies are clearer, but carbon dioxide from coal is warming the planet.

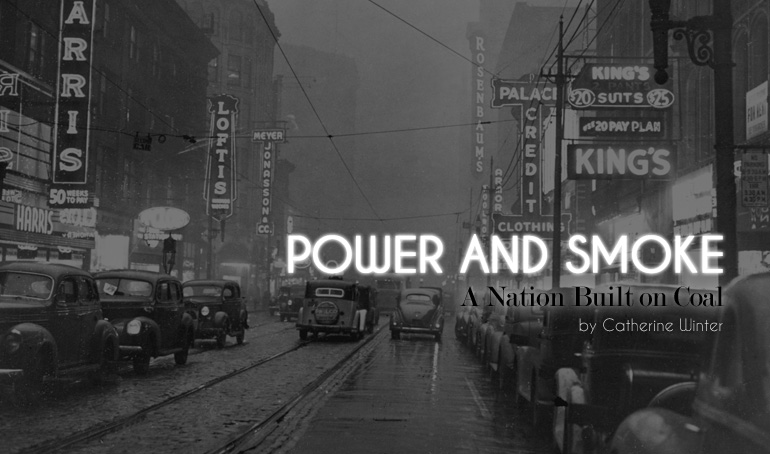

I'm Stephen Smith. In the coming hour, "Power and Smoke: A Nation Built on Coal," from American RadioWorks. First, this news.

Carnegie Mellon University Professor Joel Tarr is a pioneer in the field of urban environmental history. He showed producer Catherine Winter a slide show that he put together on Pittsburgh and coal. Edited by Chris Julin.

[Sound of sea gulls calling]

Stephen Smith: From American Public Media, this is an American RadioWorks documentary: "Power and Smoke: A Nation Built on Coal." I'm Stephen Smith, and I'm in Duluth, Minnesota, looking out at Lake Superior. I'm down in a sort of touristy waterfront area where people are feeding bread to the gulls and waiting for the aerial bridge to lift so that a cargo ship can pass from Lake Superior through this pretty narrow shipping canal into the harbor.

[Sound of ship salute]

Announcer: For the information of our afternoon visitors, the Paul R. Tregurtha is one of thirteen ships on the Great lakes called "thousand footers." These are the largest vessels sailing on the Great Lakes.

People have lined up along the canal to watch the ship come through, and it is pretty cool, because it's kind of hard to believe something this big can actually float. It towers above us, many stories high, and if you stood it on end it would be a skyscraper more than a thousand feet high.

Announcer: They are going to the Midwest Energy terminal to load with about 61,000 tons of low-sulfur, western coal.

Now, the coal comes to Duluth from the West where most of America's coal is mined these days - not in the Appalachians. It arrives in Duluth on trains, and then it gets loaded onto these huge ships and sent down the Great Lakes. Nearly 19 million tons of coal passed through this harbor last year. Some of the coal goes to factories, but most of it goes to make electric power. Nearly half the electricity in the United States comes from burning coal. We depend on coal for luxuries and necessities - really, for our very survival.

But burning coal pumps out pollution. It's a major contributor to the heat-trapping gases that are leading to climate change. Coal produces more carbon dioxide than other fossil fuels for the same amount of energy produced. In the next hour, we're going to look at how America became so addicted to coal; how our fuel choices have changed American culture and history; and we'll explore what we can do about our dependence on coal today. Producer Catherine Winter has the story.

Catherine Winter: You can look at history from a lot of angles: Who won the wars; who sailed to where; who got elected.

One question that can lead you to some surprising insights is: What were they burning? If you look at how people heated their homes, or what power source they used to make furniture or build buildings or get themselves around, you notice that the fuel people choose has a profound effect on their lives.

Dig into American history this way, and right away, you hit a thick vein of coal. Go back to the early days of radio, and you strike coal.

Radio Announcer: Who knows what evil lurks in the hearts of men? The Shadow knows! [Laughs]

It's not that the Shadow was burning coal. It's that his listeners were - and his sponsors knew it.

Radio Announcer: Before we join the Shadow in today's adventure, here's a proposition: Regardless of what coal you're burning in your furnace, order a ton of blue coal. Try blue coal for a week and see if it doesn't give you more even, more dependable, longer lasting heat! That's fair enough, isn't it?

Coal heated homes and ran factories in the 1930s, and in the '40s, coal built tanks and guns for American forces fighting in World War II. A year into the war, President Roosevelt called for an end to a mining strike.

Franklin D. Roosevelt: It is inconceivable that any patriotic miner can choose any course other than going back to work, and mining coal!

Decades later, in the 1970s, Americans looked to coal to save them from an energy crisis and oil embargos.

Television Announcer: To meet our growing demand in the future we must find an abundant energy source here in this country … We already have that energy. Coal.

Now, in the 21st century, coal is still powering the United States.

Obama: This is America. We figured out how to put a man on the moon in ten years. You can't tell me we can't figure out how to burn coal, that we mine right here in the United States of America, and make it work. We can do that.

America is a country built on coal - literally. President Obama and a lot of other people have called the United States the "Saudi Arabia of coal." America has some of the biggest, richest deposits of coal in the world.

So you might imagine that the first European settlers to reach North America were thrilled to find all that coal. You can picture them firing it up to heat their cabins and grind their grain and run their looms. The funny thing is: they didn't. Americans ignored their vast coal deposits long after coal was widely used in England.

[Music]

At the time the settlers arrived at Plymouth Rock, people back in England had already been burning coal for generations. Londoners complained about coal smoke during Queen Elizabeth I's era. A century before the American Revolution, in 1660, an Englishman named John Evelyn published one of the world's first treatises on air pollution. He complained for pages about coal in London.

Actor: That this Glorious and Antient city … should wrap her stately head in Clowds of Smoake and Sulphur, so full of Stink and Darknesse, I deplore with just Indignation.

People would have preferred to burn wood to keep warm and cook food. Wood smoke smelled sweeter. But they had cut down the forests of England. Only rich people could have roaring wood fires.

So it's no surprise that when Europeans arrived in America, the natural resource they were excited about wasn't coal; it was wood. America had vast expanses of forest. Puritan minister Francis Higginson wrote about it:

Actor: Though it be somewhat cold in the winter, yet here we have plenty of fire to warm us, and that a great deal cheaper than they sell billets and fagots in London; nay, all Europe is not able to afford to make so great fires as New-England. A poor servant here, that is to possess but fifty acres of land, may afford to give more wood for timber and fire as good as the world yields, than many noblemen in England can afford to do.

Settlers in America cleared land for farms, and burned the wood. Wood was easy, and America's coal was hard to get at. It was on the other side of mountains, and there weren't railroads or canals yet.

[Music]

By the time of the American Revolution, there were still no factories in North America. And once Americans finally began to develop factories in the 19th century, they powered them with falling water. And built them where there were rivers with enough force.

David Nye: So it's not Boston, but Lowell, in Massachusetts, which is the first big American industrial town.

Historian David Nye is the author of "Consuming Power." The book looks at how Americans' energy choices shaped the country. Nye says by using water power, Americans wound up with very different lives than people in England had. Instead of concentrated, smoky industrial cities run on coal, America had small factory towns scattered along rivers - towns like Lowell.

Nye: It was a tourist attraction and Andrew Jackson - then President of the United States - made a special detour to see the Lowell factories when he made a tour of New England because that was a significant sight, something he'd never seen: a whole town of factories.

Nye's book talks about how in its first centuries, America relied on water power and muscle power: Mules and horses and humans used their muscles to plow fields and make furniture and transport goods. It wasn't a lot of power. And that meant Americans didn't have a lot of extra material goods. Nye says historians can tell what people owned by looking at their wills.

Nye: They'll list things like, one gun, you know, one bed, one plow; very specific things which suggests that under miscellaneous there must be very small things indeed.

People didn't own much, and they made much of what they did have themselves. They didn't have buying power, or things to buy - until they harnessed the power of coal.

American settlers who pushed west, across the Appalachians, discovered an astonishing abundance of coal. George Washington himself wrote about it. He passed through the area where the Monongahela and Allegheny Rivers join together and form the Ohio River, and he noticed coal right on the surface. You could walk up and kick it. Because of coal, the fort at the river forks was destined to become a major industrial city - the city of Pittsburgh.

Ted Muller: Early on there is recognition that coal is a ready source for heating homes, heating businesses and powering blacksmiths and small metal-making industries and things like that.

Ted Muller teaches history at the University of Pittsburgh.

Muller: By the time you get to the 1830s or '40s industry - iron, glass, coal mining are really becoming pretty major activities…. From that point on this is the city people think it is. The city of iron and eventually mass-produced steel.

As Pittsburgh developed, the rest of the country began to want coal, too. One big reason Americans developed canals and railroads was to get coal from one place to another. And this is where Americans began using steam engines in earnest - to run trains and boats. A steamboat could move upstream without mules to haul it. Steam power was convenient - and it was dangerous.

Nye: The science of building steam engines was not so understood, so occasionally steamboat engines would blow up, like a bomb going off.

Historian David Nye.

Nye: I mean there was no chance to get out of the way. If you happened to be nearby, you were going to be killed. Steamboat explosions were a real plague in America in the 1840s and 1850s, and we might look back today and say, "Well why would they stand for this?" But they tended to see these things as acts of God, didn't see them as human error, but rather as, "Well it's the inscrutable Almighty who has let this happen," and then they would have a big funeral and everybody would weep and give some money to the widows and children and go on and mine some more.

The "inscrutable Almighty" tends to figure prominently in the story of coal - and so does the devil. Some people in the 1800s used satanic images when they talked about smoky steam engines and sulfurous coal mines.

Barbara Freese: Coal has always been seen in this dualistic way. Some people saw it as a gift from God, and others really connected it with evil.

Barbara Freese is the author of "Coal, a Human History." She says in the 1800s, a lot of theologians who wrote about coal saw coal deposits as signs of God's favor.

Freese: And that's why God gave America so much coal and gave England so much coal because he essentially wanted English-speaking countries to have a controlling influence over world affairs. So it was seen really as further evidence of our manifest destiny.

If God wanted Americans to fire up coal and build things, he must have been pleased with Pittsburgh. In 1841, a man from Cincinnati named Charles Crist wrote about a visit to Pittsburgh. He described how it looked to an approaching traveler:

[Music]

Actor: A dense cloud of darkness and smoke, visible for some distance before he reaches it, hides the city from his eyes until he is in its midst…. As he enters the manufacturing region, the hissing of steam, the clanking of chains, the jarring and grinding of wheels and other machinery, and the glow of melted glass and iron, and burning coal beneath, burst upon his eyes and ears in concentrated force. …

The very soot, falling, like snow-flakes, fastens on the face and neck, with a tenacity which nothing but the united agency of soap, hot water, and the towel can overcome.

Crist assures the reader he's not trying to disparage Pittsburgh. The soot and noise are the tax citizens must pay, he says, "for the prosperity and importance of their city."

Pittsburgh was ahead of other cities in adopting steam power. But the use of the steam engine was growing. In 1876, Pennsylvania played host to an awesome display of this new power.

Freese: In 1876 there was an enormous Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia. And it was of course it was celebrating the fact that the nation was a century old but it was also in retrospect kind of a[n] industrial coming-of-age party.

Barbara Freese says millions of people came to see the wonders on display at the Centennial Exhibition.

Freese: In the Machinery Hall they had thousands of interesting, different, new, innovative machines. And they were connected by something like eight miles of connecting shaft to one giant steam engine in the middle. And in the opening ceremonies of exhibition… President Grant came, they had a big choir singing "Hallelujah" chorus, they had 100,000 people there and then at just the right moment, the president flipped the switch and suddenly eight miles of shaft start turning and thousands of different machines start operating all around Machinery Hall.

[Music: "Hallelujah" chorus]

Freese says visitors were dazzled. And they saw this display for what it was: a moment separating America's first hundred years from its second hundred, dividing its agrarian past from its industrial future.

Industrial cities began to crop up around the country. People didn't have to put the factories where the power was, on rivers. With coal, they could bring the power to the factory. And that meant large clusters of factories were possible, surrounded by densely-populated neighborhoods of workers.

In the early 1900s, social reformers surveyed conditions in Pittsburgh. One wrote about company housing next to a steel mill.

Actor: I found half a thousand people living there under conditions that were unbelievable; back-to-back houses with no through ventilation; cellar kitchens; dark, unsanitary, ill-ventilated, overcrowded sleeping rooms; no drinking water supply on the premises; and a dearth of sanitary accommodations that was shameful…. Sluggish clouds of thick smoke hung over the roofs and the air was full of soot and fine dust. Noise pressed in from every quarter - from the roaring mill, from the trolley cars clattering and clanging through the narrow street.

Life was at least as miserable for coal miners. And more dangerous. Mining offered multiple ways to die - explosions; cave-ins; suffocation.

At the Senator John Heinz Museum in Pittsburgh, one exhibit commemorates mining deaths at the turn of the century. There are photos of men on their hands and knees in narrow shafts, digging coal.

Anne Madarasz: So this is The Darkest Month exhibit.

Anne Madarasz is the museum director.

Madarasz: And this really exhibit focuses on December 1907, when over 700 Americans died in coal-mining accidents around the country.

More acts of the "inscrutable Almighty."

But as coal taketh away, it also giveth. In the museum, you can see how coal also made many people's lives more comfortable and convenient. For example, there's the exhibit on Heinz products. H.J. Heinz grew up in Pittsburgh.

Madarasz: And he makes his foray into the food industry in the 1860s with horseradish and ketchups and other condiments.

New, steam-powered machines let Heinz start canning food on a large scale.

Madarasz: With the adaptation of canning technology, you begin to see him packaging things like soups.

And baked beans and vegetables.

Madarasz: Suddenly there's produce in the winter, and suddenly you don't have to grow or can everything you'll need to survive. So I think it changes not just people's diets but their habits as consumers and as, in a sense, survivalists. They don't have to spend so much time on the land. It frees them from kind of the bonds of the lands for other pursuits.

Heinz made a lot of money. Coal power let industrialists start amassing fortunes, and even poorer people could afford cheap, new mass-produced goods. David Nye says the new energy source meant people could produce more goods than they really needed, and could buy things they didn't need, just for status.

Nye: Wealthy people had maybe always engaged in conspicuous consumption. You could say that. You can probably find examples going back a very long way in history, but the idea that the majority of the population can do it, that only comes with the coal-based economy, I think.

The expression "conspicuous consumption" comes from a book published at the turn of the century by economist Thorstein Veblen. A new, much larger class of consumers was emerging. They bought stuff, and they bought experiences.

[Music]

Coal had begun to power electric generators, and people went out to see the new electric lights in dance halls. They shopped at new "department stores," big, brightly lighted interior spaces, where they could see a famous painting or hear a lecture - or buy things. And they escaped from the city to new amusement parks.

[Sound of a roller coaster]

On a Saturday morning, kids stream into Kennywood amusement park in Pittsburgh. The park is 113 years old. It has modern, whizzing, scrambling, splashing rides, but it's still got some of the old ones, too.

Andy Quinn: Now this is the oldest of our roller coasters. This is the Jackrabbit, opened in 1920.

Andy Quinn's been working here since the 1970s. His family owned this park for generations, starting in 1906. But the park is older than that. Before the turn of the century, a man named Anthony Kenny owned this land. He mined coal here and he farmed. And he let people come out from the city for picnics.

And then in 1898 a trolley company built a line to carry workers to and from the Andrew Carnegie steelworks.

Quinn: The reason Kennywood came into being is Mr. Andrew Mellon who owned the trolley line - he also owned the steelworks - actually wanted people to ride the trolley when they weren't going to and from their jobs.

So he bought the park. This was a trick trolley companies around the country were using. They built amusement parks to entice weekend and evening riders. Andy Quinn says people came here to swim and boat, and dance in a pavilion. And then came a few rides; a tunnel of love; a merry-go-round. But all along people came for picnics. They still do. It's a Pittsburgh tradition. On one edge of the park are rows of picnic tables, shaded by trees overlooking the river.

Quinn: Now there's the Edgar Thompson Works right out there. That is the last functioning actual steel mill here in the valley.

Quinn points across the river to some enormous industrial buildings spread along the opposite bank, far below. He says that steel mill still operates, but it used to have a lot more workers - thousands of them. And at night it put on a show. Quinn says when he was young, he and other Kennywood employees used to hang out up here after the park closed.

Quinn: And what happens at night on the mills in the old days was they would open their hearths up and blow all that ash and stuff, but it would light up the sky, it was so bright, it was almost like daylight…. Every morning you could come in, and I actually started, there was a ride right here called the Turnpike ride - it was a car you got in and drove yourself on a track. You could write your name in the hood of that car because of all the mill dust that pumped out every night. My great-grandfather had a saying: "The more dust they dump on us, the more money we make."

Because as long as the mills were running, workers had money to spend.

This has always been coal's tradeoff. It provides the power to run steel mills and roller coasters. And it makes ash and smoke.

At first people only thought of coal smoke as an annoyance. They had no idea it could be deadly.

[Music]

Smith: This is Stephen Smith. You're listening to "Power and Smoke, a Nation Built on Coal" from American RadioWorks. Coming up:

Newsreel: A death-bringing fog settles over Pennsylvania's bustling industrial town of Donora. Twenty people die, 400 others are stricken with respiratory ailments.

To see historic photographs of Pittsburgh from the days when coal smoke clogged the air, visit our Web site at Americanradioworks.org. While you're there, you can download this and other American RadioWorks programs. That's at Americanradioworks.org.

Sustainability coverage is supported in part by the Kendeda Fund, furthering values that contribute to a healthy planet. American RadioWorks is supported by the Batten Institute at the University of Virginia's Darden School of Business. More at Americanradioworks.org.

Our program continues in just a moment, from American Public Media.

Stephen Smith: You're listening to an American RadioWorks documentary: "Power and Smoke: A Nation Built on Coal." I'm Stephen Smith

People in the coal industry feel like they're under attack these days. Coal has a bad name: Accidents in coal mines; mountaintop removal mining; acid rain; and, especially, global warming. Burning coal produces more greenhouse gases than other fossil fuels for the same amount of energy. But coal's supporters are quick to point out that there is no ready alternative. Coal provides nearly half of America's electricity. It's cheap. It's abundant.

Over the last two centuries, Americans have gotten used to the comforts and conveniences coal provides. Coal's environmental costs are the price of prosperity. And until fairly recently, Americans didn't really realize what those costs were. By the time they knew, coal was embedded in American life.

Catherine Winter continues our story.

Cashier: Did you pay yet?

Woman: No, we need to pay.

Cashier: Okay, that'll be four dollars each, or eight dollars total.

Woman: Okay.

Catherine Winter: It's a sunny Sunday and people are lining up to take the Duquesne Incline in Pittsburgh. The incline is an old funicular, built in 1877. A little car, like a train car, climbs tracks up a steep slope just across the river from downtown.

The Incline was built to haul workers and goods up Mt. Washington. Now, it mostly hauls tourists. From the top, they can look out over Pittsburgh at the green hills, the bridges big and small crossing the rivers; the tall buildings downtown hemmed in by water.

[Sound of woman and child on viewing platform]

It's a spectacular sight, but in the Incline's early days, you wouldn't have gotten such a clear view from here.

Joel Tarr: Pittsburgh was known historically as the Smoky City.

Joel Tarr is a professor of history and policy at Carnegie Mellon University. He collects pictures of Pittsburgh for lectures. One shows that view from the top of the Incline, 100 years ago.

Tarr: This is probably a 1909 picture.

Winter: Wow.

Tarr: This picture shows you a very bad day of very bad pollution, where you barely can see from Mt. Washington the structures, the high-rise structures of the downtown.

Tarr has older pictures of Pittsburgh, too, paintings and drawings. They show smoke pouring from steamboats and factories and trains and the chimneys of houses.

Tarr: And when you look at early images of Pittsburgh there's a very conscious attempt by the person, the artist, before photography for instance, to let the smoke be very obvious. Let it be seen. It was a sign of progress; it was a sign of growth; something to be proud of.

In fact, Tarr says, some people thought the smoke itself was a good thing.

Tarr: In the 19th century, there were some physicians saying that smoke was actually beneficial for your health; it could help clear your system up, breathing in coal smoke. Undoubtedly lung diseases were rampant, but we're talking about a period when emphysema and things like this were just really basically not understood at all.

The smoke in Pittsburgh persisted well into the 1940s.

Tarr: Pittsburgh, for instance, was known as a "two shirt a day" town - you had to take an extra white shirt downtown, because by noon your shirt collar was smudged up. I like to say that Pittsburgh, "Ring around the collar" was invented in Pittsburgh.

Tarr has black-and-white shots of downtown from the '30s and '40s. Several photos look like they were taken at night, but they weren't. In one, people walk past lighted neon signs advertising pianos, and credit. A bus passes with its headlights on.

Tarr: Downtown Pittsburgh, in midday, 1944, 1945; streetlight's on, as you can see.

Some Pittsburghers protested that the smoke was ruining buildings and making a mess for people to clean up. Women, especially, fought for smoke controls. And after World War II, the city made people stop burning coal at home. Homeowners converted furnaces to natural gas, and the skies got clearer. But smoke persisted around the country in other industrial towns, big and small.

[Sound of a truck passing]

Like Donora, Pennsylvania. It's a little town up the Monongahela River from Pittsburgh. A lot of the stores downtown are closed up these days. But resident Charles Stacey remembers when it was a busy place.

Charles Stacey: On payday, well, any weekend, Friday night and Saturday night you could barely walk on the sidewalks here in Donora there were so many people out doing their shopping. And it looked like some of big cities during Christmas shopping season every weekend.

People had money in their pockets back in the '40s, when Stacey was a boy, because they worked at the zinc mill or the steel and wire plant. Both mills put out a lot of smoke - coal smoke mixed with other fumes. People who lived here up through the 1960s will tell you that the lush hills on the other side of the river used to be utterly barren - every green thing killed by the stuff the mills were kicking out. Houses were blackened with soot.

Stacey: We grew up, and we thought that smog and fog were way of life. So often times we walked to school and really couldn't see where we were going. It's a good thing we knew the lay of the land.

Mary Janet Henry: So, yeah. So it was usual then that that October when the smog came along that we walked to school in the fog and didn't think too much about it except that it was a little maybe more foggy that day.

That's Mary Janet Henry, Charles Stacey's sister. She's recalling the day in October of 1948 when smoky fog filled the valley … and stayed. It smelled bad.

Stacey: Maybe more of a taste than a smell that I recall. And you'd breathe that in and it irritated your throat lining.

Henry: Yeah, we lived just block away from the zinc works and there was always that sulfur smell in the air, and we got used to it. I mean we played outside in the vacant lots and we just got used to that atmosphere and that environment so we didn't think much of it until the people started dying that weekend in October.

A temperature inversion held the smoke in the valley. Twenty people died. Thousands more got sick. Many Donora residents didn't know what was happening until they heard it on the national news.

Newsreel: A death-bringing fog settles over Pennsylvania's bustling industrial town of Donora. Residents have difficulty in breathing the murky air as the town is plunged into darkness. Oxygen tents care for sufferers in the local emergency hospital.

After several days, the weather changed and the toxic cloud lifted. But the incident made a deep impression on the country. If concentrated smog could kill people so quickly, surely breathing the fumes from industrial sources every day was dangerous, too. The Donora disaster of 1948 is often credited with being the wake-up call that eventually led to the Clean Air Act, first passed in 1963. Recently, the city put up orange banners that say "Clean air started here." And some Donorans created a smog museum.

Don Pavelko: When I first started talking about this in 2007, yeah, people thought I was nuts.

Don Pavelko is on Donora's city council, and he heads the committee that got the smog museum started in 2008.

Pavelko: But as time went on and as people came and looked, I think there's a bit of pride now in Donora that, hey, you know, we saved a lot of people's lives here. And you know, the people that died here in Donora and the people that lived through this, it went for the betterment of the world.

The museum is easy to find if you go to Donora - right on the main street downtown with a big orange sign. The collection includes artifacts like the oxygen tanks firefighters carried to people struggling to breathe during the smog incident. To honor those firefighters, Donora now holds a smog parade in October.

Pavelko: I envision maybe in 20 years maybe people will be coming to Donora for the Halloween Smog Parade like they go to Pasadena. You never know. You gotta try.

The folks behind the museum and parade are hoping tourism will bring jobs to Donora. It's been tough since the mills closed. In fact, in spite of what happened here, Don Pavelko thinks if someone wanted to open a steel mill in Donora today, the city would welcome it.

Pavelko: It sure would be hard to turn down jobs and uh, and a new tax base. I think for anybody. You know, they're talking, President Obama is talking about "clean coal," so I'm sure there's, if the right company comes in with the right technology, it wouldn't be a problem.

[Music]

Other people in Donora say the same thing. They love the pretty setting the town is in - with all the trees that can grow now that the mills are gone. But they'd take industry back, for the jobs. Drive back up the Monongahela Valley toward Pittsburgh and you can see other communities that have made this same trade. The shop windows are boarded up, but there's no soot falling on the laundry hanging out to dry, now that the steel mills are gone. Urban environmental historian Joel Tarr says both the air and the water are cleaner.

Tarr: The rivers today are probably cleaner than they've been in a hundred and some odd years, and the fish population is very good, too.

It's a rainy afternoon, and Tarr is driving around Pittsburgh, pointing out ways the city has changed since the mills closed.

Tarr: Now this is a very interesting development along here on the left that you're gonna see. It is a water slide park that was developed on the site of the old Nestor Machine Works.

Winter: Wow.

Tarr: And it joins the old Homestead site, so you can see it.

The Homestead Steel Works site is a shopping mall now. Not far away, a huge pile of steelmaking waste has trees growing on it now, and dozens of new houses. Throughout the city, soot-covered buildings have been scrubbed clean. Pittsburgh isn't a smoky steel city anymore. It's green and prosperous, with thriving universities, hospitals, and a high-tech industry.

Tarr: Now you go around the city now and you get a feeling of a city that's really moving ahead, you know? Doing things, developing…

The big industries in Pittsburgh now don't use blast furnaces or steam engines. They use electricity. The switch to electricity is one of the big reasons smoky cities are cleaner today. Today, the power comes into the city on high-voltage lines. But it still comes from coal. It's just that the coal is burned somewhere else.

[Music]

Drive from Pennsylvania down into West Virginia, and you see billboards that say, "Yes, coal." Even though most of America's coal comes from the West now, West Virginia is still coal country - with coal mines, and coal power plants.

Charlie Powell: You going with that other tour or with this one?

This is a coal-burning power plant on the Ohio River in West Virginia. It's called Mountaineer, owned by American Electric Power. AEP is one of the largest consumers of coal in the western hemisphere. At its Mountaineer plant, some reporters are getting outfitted with hard hats and earplugs and safety glasses for a tour.

Powell: Everybody got glasses?

Woman: Yeah.

Man: I can see much better now.

The plant manager, Charlie Powell, gives the reporters a briefing while a photographer for a Norwegian newspaper snaps photos. Powell explains how Mountaineer reduces its pollution.

Charlie Powell: When you look at the stack and you see this billowing stuff coming out, environmentalists say, "Oh look at that polluting stack!" Well, what you see is water vapor. It's just fog, clouds, whatever.

That's because the Mountaineer plant has all kinds of equipment added onto it to clean up the exhaust from burning coal. And recently, it put in a new system. It's an experiment. It captures some of the carbon dioxide the plant emits so it won't be released into the atmosphere. CO2 from electric plants is a major contributor to climate change. A lot of people are hoping this new "carbon capture" technology will make it possible to keep burning coal without warming the planet. That's why the reporters are here. People come from around the world to see this plant.

Powell: We've probably averaged at least three tours a week for the last six months.

Powell and a couple of other AEP employees take their group up into the huge building that houses the coal furnace. It's dark and stiflingly hot.

Powell: This is not bad, this is a good day! [Laughter]

Woman: Yeah, you haven't been to the hot part yet!

It's a relief to emerge onto the roof, 20 stories up. You can see a huge coal barge on the river behind the plant. You can see a coal pile many acres large. And you can see the rest of the plant - an enormous vase-shaped tower giving off steam and a cluster of big buildings with pipes and ducts and scaffolding. And then engineer Brian Sherrick starts to get technical.

Brian Sherrick: Okay, um, right now we're on top of the boiler house on the other side. Uh, to your left is the S.C.R. - selective catalytic reduction, removes the "NOx" … Okay then, these large, stainless steel vessels that has like a hood, goes into the stack… that's where the SO2 removal takes place.

So, SO2 is sulfur dioxide. It causes acid rain. "NOx" are nitrogen oxides. They contribute to smog. The federal government requires power companies to reduce emissions of these gases, so AEP puts this clean-up equipment onto some of its power plants. So far, the government doesn't require them to reduce CO2, but company officials believe that legislation is coming.

So, this experiment: Mountaineer is capturing a small amount of the CO2 it emits, and then injecting it deep underground for permanent storage.

Brian Sherrick is the manager of the carbon capture project. He takes the group out onto the grounds, past the huge cooling tower, with water running down its sides. He points out where CO2 is being pumped down into the earth, into pores in the rock a mile below.

Pushing gas into rock isn't a new idea. Fossil fuel companies already force gas underground to flush out oil and natural gas.

Sherrick: You know we're applying basically the same principals, we're just busting through the cap rock, we're monitoring, we're injecting it in there.

This is what people mean when they talk about "clean coal." Clean coal isn't a type of coal; it's an idea - a way to capture coal's greenhouse gas emissions. So far, this technology looks like it's working. The question is: Can it work on a large enough scale to do anything about climate change? The folks at the Mountaineer plant are the first to acknowledge that large-scale carbon capture and storage will be very, very difficult.

Powell: When you start talking about catching and capturing CO2, it's a massive thing to do if you look at putting it on all the coal that's burned in the country today.

Charlie Powell's been working at the Mountaineer plant since it was built 30 years ago. Over the years, he's seen the government hand down more regulations on coal plants, and he's seen the plant add equipment to clean up its emissions. He says there are always bugs to work out. And carbon capture has some big ones. For example, there's the storage problem. Currently, Mountaineer is storing carbon on its own property. But it's only capturing and storing one-and-a-half percent of the carbon it emits. When it expands the project, it'll need to store the carbon on someone else's property

Powell: There's a lot of barrel-of-fishhooks when you deal with the public and the media and how do you prove something that you haven't done is intrinsically safe and get the people to agree you can store stuff underneath their property, because when you're pumping into a rock formation, you don't know exactly where it's going, how fast it's going, in which direction.

And a lot of rock formations won't work for carbon storage. Many power plants would need to ship the CO2 elsewhere in pipelines. That adds costs, and it's already expensive to capture and store carbon. This project cost AEP more than $70 million. The next phase of the project will cost $668 million, and it'll still only capture about 17 percent of the plant's carbon. Half of the money for the next phase will come from the government. There's federal money for carbon-capture projects. But Powell says it's not enough money to make a noticeable dent in the carbon that power plants produce.

Powell: I saw an article here just today about the government proposing another two-and-a-half billion dollars for, "Oh, it's a lot of money, to run some more tests on capturing CO2…."

But, do the math. It's going to cost $668 million to capture less than a fifth of this plant's CO2.

Powell: So you're talking three point five billion dollars just for this facility alone if we were to put this technology onto 100 percent of the output.

And Powell points out a lot of power plants don't even have the physical room to add this equipment. And capturing the carbon takes energy. To capture the CO2, you have to burn more coal, which means mining and transporting more coal.

Still, power companies are looking hard at carbon capture. Because if the government starts to require limits on CO2, their only other option is to find a way to produce electricity with something other than fossil fuel.

Standing with Brian Sherrick by Mountaineer's cooling tower, AEP spokesperson Melissa McHenry says about half of the country's electricity comes from coal. Finding a replacement won't be easy.

Melissa McHenry: A new nuclear plant is running in the range of, you know, $14 billion. And then, that's presuming you can actually get a permit to build one somewhere.

Sherrick: It takes 10 to 15 years to build one if you build it.

McHenry: And we're investing in renewables, we have a significant renewable portfolio, but even if you double the cost of power from this plant, we generate power for three cents a kilowatt hour here, so you go to six cents. Most renewable projects, you know, wind, solar, are in the range of 15 to 20 cents a kilowatt hour.

Whatever the answer is to producing cleaner energy, it's going to take time. And many climate scientists say that there isn't time. Something has to be done fast to reduce the emission of heat-trapping gases. So, this raises a question. If reducing CO2 can't be done quickly on the supply side, could it be done on the demand side?

For generations, Americans have been increasing their electricity use. Can that trend be reversed? And even if it could, could individual consumers reduce their energy use enough to make a difference?

Pretty often the answer you hear is "no." But this man begs to differ.

Tom Dietz: I'm Tom Dietz. I'm a professor of sociology and environmental science and policy at Michigan State University. I study the human dimensions of global environmental change. So a lot of my work looks at individual behavior -how people feel and act with regard to environmental issues.

For example, Dietz looks at how you can persuade people to cut back their energy use -the fascinating psychology of behavior change. You'd think people would be motivated by money, but Dietz says money only goes so far. A better motivator is a form of peer pressure. Give people a sense that changing their behavior is a "normal" thing to do. That other people like you are doing it.

Dietz: We've all seen these hangers in hotels that encourage us to reuse our towels for several days. The thing that best encourages people to do that is a message on that little towel hanger that says, "A high percentage," whatever it may be, it's often around 60 percent, "of the people who stayed in this room in the past have reused their towels." That trumps any other kind of message that you can put on the towel.

Tom Dietz and some colleagues recently wrote a paper looking at reducing household energy use.

Dietz: Overall the household sector is about 38 percent of total U.S. greenhouse gas emissions. I think people often don't appreciate how important households are. The U.S. households amount to eight percent of total global greenhouse gas emissions.

Dietz and his colleagues figured there's no way to get all those people to stop using energy entirely. But what if you were realistic? What if you just looked at energy reduction programs that work - like the towel hanger program - and tried to replicate them? Get some people to drive a bit less, some others to weatherize their houses.

Dietz: Our analysis shows that you could reduce greenhouse gas emissions or energy consumption in U.S. households by 20 percent. That reduces total U.S. greenhouse gas emissions by 7.4 percent.

So, which programs work to change people's energy habits? Dietz says one thing that helps is to let people see how much energy they're using. Often, consumers have no idea. The electricity meter is on the outside of the house, where you don't see it, and you can't tell what's making it spin, and who knows what those numbers mean, anyway? Better information can make people change.

Man: Hello.

Winter: Hi, are you Adam? Hi, I'm Catherine. Who's this?

Man and woman: This is Story. [Dog growls and barks]

This is the home of Adam and Cassie White in St. Paul. Last winter, they got a call from Xcel Energy asking if they'd like to be in a pilot program. They said yes, and Xcel gave them an Energy Detective.

Cassie White: Yeah, you want to see?

Winter: Yeah.

It's in the kitchen. It looks a little like an iPod, but its readout shows how much energy the Whites are using.

Cassie: Do you wanna grab a glass honey?

They show me what happens when they turn on their ice dispenser.

Cassie: Okay, so this is the energy detector. TED. And like right now we're at 51.

Adam: Because the refrigerator is running.

Cassie: Right. So I'll just do water to show you, that's not a lot it goes up to 53.

[Sound of ice machine]

Cassie: Oh, see? 76. Or, I'll turn on the oven.

[Sound of oven beeping]

Adam: And it should jump…

Cassie: It'll jump. You'll actually be able to see it go on. Up, there we go.

When Adam and Cassie got the Energy Detective, they ran around the house turning things off and on to see how much electricity they used - and how much it was costing them.

Cassie: Smaller things added up. As soon as we could see it, it's when we started realizing, "Well maybe I don't need this light on."

Adam: Or maybe I don't need to leave this computer on overnight. I can turn it off and just boot it up in the morning. It's not that long of a time.

Cassie says she was shocked by how many of her electronic gizmos used power even when they weren't on - like the Wii, and the TV, and her phone charger. She and Adam unplugged them. They used the toaster oven instead of the oven. They insulated so they could use an electric heater less often. And they cut their power bill by a third.

Cassie: We get a report from Xcel…

This is the other thing Xcel is trying out. It's sending some customers bills that show how their energy use compares to their neighbors'. Cassie and Adam are 16th out of a group of 100 similar neighbors. Only 15 households use less energy.

Cassie: I'm extremely competitive and I always say that. I'm aiming for top ten. It'd be a point of pride for me. Uh, but I'd love to see how we can save even more.

Of course, not everyone is motivated by competition. Some people might see that their energy use is lower than their neighbors, and decide it's okay to use more. But sociologist Tom Dietz says research has found an answer to that problem.

Dietz: If you put a little smiley face with the message that you're well below your peers, people's energy consumption doesn't go up in response; it stays down. So that's sending a little social signal that you're below your neighbors and that's good. And that seems to work in terms of keeping people's energy consumption down.

The study Dietz and his colleagues did looked at a list of actions like the ones Adam and Cassie White tried - unplugging things, weatherizing.

Dietz: What we find is that behaviors at the household level that don't involve changes in lifestyle or any kind of real major sacrifice, they just reduce the amount of energy that we're wasting, can take us long way. We could get a reduction of five percent in total U.S. greenhouse gas emissions in something like five years by simply promoting the easiest of the behaviors on our list.

Dietz says that's not enough to stop climate change - but maybe it could buy time to get technological fixes in place - like carbon capture, or renewable energy.

Around the country, power companies are using techniques like smiley faces and Energy Detectives to get customers to cut back. It's a far cry from what they did a generation or two ago. Back then, electric companies tried to get customers to use more power, so they could make more money.

Nye: Back in the 19-teens and '20s, they actually had to send people around door-to-door.

Historian David Nye.

Nye: They would get salesmen to come and they worked it out so that they would sell things that were appropriate for the time of year. When it was dark in the winter, they would try to sell you a light. When it was hot in the summer, they'd try to sell you fans.

Nye says the idea wasn't to make money by selling those products -

Nye: The point was to get people to use the electricity, so to get used to the idea that that was the best way to iron, or that was the best way to make coffee was an electric percolator, or the best way to, uh - some of the things seem silly to us today, perhaps - the best way to light your cigar was with an [laughing] electric cigar lighter that you would have next to your easy chair.

These new devices promised to save people time, and make life easier, and indeed they apparently did reduce the need for servants. The number of households that employed servants shrank between World War I and the 1950s as electrical appliances gained hold.

[1950s Jingle: "…as easy as can be when you live better, electrically! You can have your cake and you can eat it. Make life sweet, it's hard to beat it! What a thrill to be so free, when you live better electrically!]

Power companies pushed the idea of the "electronic home" in the 1950s. Their ads tie electricity to freedom, and progress, and being a successful middle class American. Here's a sitcom-style film from 1952 called "Young Man's Fancy," made to promote electric razors and water heaters and kitchen appliances.

Girl: Dad kinda fancies himself quite a cook since we got our electric range, doesn't he?

Mother: Mm-hm, and he's pretty good at it, too.

Girl: Mother, wouldn't it be slick if we had an electric ironer like Sally's mother has?

Mother: Of course it would, and I'm looking forward to having an electric dryer, too. Just think, then we'd have a complete electric laundry!

All these new gadgets promised to lighten the workload, especially for women. But historian David Nye says women didn't actually wind up doing less housework. In fact, appliances such as washing machines may have added to a middle-class woman's work.

Nye: People who had a little money used to take their laundry out. You know, they'd get somebody else to wash it in an industrial establishment which had machines doing it. But once a machine comes in the home, that work of running the machine and processing, in a sense, all the laundry, becomes the mother's job, typically.

And once they had home machines, people started washing clothes more often, making even more work. Other cleaning tasks got done more often, too.

Nye: Home economists all through the 20th century have done studies of the hours spent on housework, and they find that it's pretty consistent. It doesn't change much.

Still, Americans equipped their homes and their offices and their factories with electrical machines of all kinds. They demanded more and more electricity - and burned more and more coal. In the 1950s, most of the coal burned in America was used by industry. But by the 1960s, most coal was used to generate electricity. Today, more than 90 percent of the coal used in America goes to make electricity. The amount of coal Americans use has doubled since 1950. In the 21st century, Americans are burning more of this old-fashioned fuel than at any time in the past.

[Music]

Coal has made a lot of things possible: canned food, and skyscrapers, and roller coasters and MRI machines. Coal gave Americans a lifestyle they didn't even know they wanted - comforts and conveniences no one dreamed of 100 or 200 years ago.

Coal was easy, and cheap. There was so much of it.

And there still is. By some estimates, there's enough coal to last the United States another 250 years.

But we can't say today that we don't know what coal's trade-off is. Today, you won't find doctors saying coal smoke is good for you. But it's hard to shake off an addiction when the drug is near at hand. All the infrastructure is in place to keep digging coal, and shipping it and burning it. And American power companies are building dozens of new coal plants today.

[Music]

Stephen Smith: You've been listening to an American RadioWorks documentary, "Power and Smoke: A Nation Built on Coal." It was produced by Catherine Winter and edited by Mary Beth Kirchner. The American RadioWorks team includes Ellen Guettler, Kate Ellis, Ochen Kaylan, Frankie Barnhill, Craig Thorson and Judy McAlpine. Special thanks to Chris Julin. I'm Stephen Smith.

To see photographs from "Power and Smoke" and to learn more about the history of coal in America, visit our website at Americanradioworks.org. There, you can download this and other American RadioWorks programs.

Sustainability coverage is supported in part by the Kendeda Fund, furthering values that contribute to a healthy planet. American RadioWorks is supported by the Batten Institute at the University of Virginia's Darden School of Business. More at Americanradioworks.org.

Thank you to the New York Ensemble for Early Music for permission to use "English Dance," from Istanpitta, Vol. 2.