part 1 2 3 4

Throughout much of August and September, allied pilots flew the precarious journey from Brindisi in southern Italy to Warsaw to drop supplies. Losses were heavy and many planes were shot down before reaching the capital. There were 19 airdrops throughout August, but to many Poles it felt like a meagre reward for their war efforts on the Western Front. William Fairly, a South African pilot, spoke to Radio New Zealand in 1982.

"There was no difficulty in finding Warsaw," said Fairly. "It was visible from 100 kilometres away. The city was in flames and with so many huge fires burning, it was almost impossible to pick up the target marker flares."

"Flak over Warsaw itself was heavy," said American Air Force pilot Ian Miller describing the operation in a 1944 recording. "We dropped canisters containing guns, ammunition and medical supplies by parachute."

"Permission was sought from the Russians to run a form of aerial shuttle service," said Fairly. "That is, our aircraft could fly to Warsaw, drop their supplies and carry on the short distance to a Russian airfield. Had this permission been granted, the assistance to Warsaw would have been much easier and greater. Some allied pilots with damaged planes and malfunctioning instruments strayed over Russian-held territory and were fired on by our so-called allies, the Soviets."

In the eastern city of Lublin the Soviets had set up an acting administration consisting of Poles loyal to Moscow. Back in London, Churchill was putting pressure on Stalin for permission to use Russian airfields, but he was also having to push Roosevelt to cooperate. The American President didn't want to upset Stalin.

Nevertheless, on August 20, they made a joint appeal.

"We are thinking of world opinion if anti-Nazis in Warsaw are, in effect, abandoned," Churchill said to Stalin. "We hope that you will drop immediate supplies and ammunitions to the patriot Poles of Warsaw, or will you agree to help our planes in doing it very quickly? The time element is of extreme importance."

But two days later, the appeal was brushed aside by Stalin. On the August 25, Churchill proposed to Roosevelt that they would send a toughly worded message to Stalin that would put him on the spot: "We propose to send aircraft unless you directly forbid it."

Roosevelt did not agree.

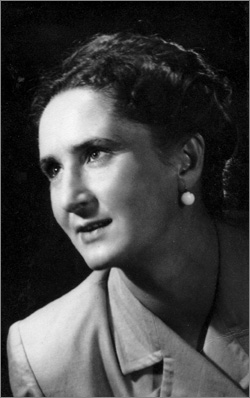

|  | | Halina Martinowa |

"I do not consider it would prove advantageous," said Roosevelt, "to the long-range general war prospect for me to join with you in another proposed message to Stalin, but I have no objection to your sending such a message if you consider it advisable to do so."

Most of the airdrops that did make it were falling outside Warsaw into the Kampinos forest. By the end of August, people in the Old Town were starving.

"We ate all the horses," says Slawinski, "then all the dogs and cats, pigeons of course. And then there was nothing left. We were eating dogs, very nice meat, dog, you know. And it was becoming sort of more and more hopeless. It was - we knew that nobody will come to our rescue."

Halina Martinowa remembers that "The main problem was water. Being just a few steps from the river, we couldn't get it because it was under such a terrific fire. So every bucket of water - it was at least one or two lives. Can you imagine the wounded who are dreaming about a cup of water?"

Go to part 2

|