part 1 2 3 4

As for the Germans, to begin with, they were taken aback by the strength of the resistance.

"As we arrived," says Hasso Krappe, an officer with the 19th Panzer division, "a motorcycle messenger came and requested that an officer from our division report to headquarters. That was me. By telephone, I was a connected to the 9th regiment, and I heard rifle fire from outside. Bullets were flying through the window and I had to hide with the phone under the table. Later a Polish newspaper wrote: German officer hiding under the table."

Poles communicated to the outside world by radio. Each broadcast began with a Chopin piano concerto followed by news from Warsaw, which was often read by John Ward, a British pilot who had escaped from a German prisoner-of-war camp. In those early days "Radio Lightening" or in Polish, "Blyskawica" was able to report some notable successes.

"This is Warsaw calling," said the report from Blyskawica. "Of our achievements in the past day the most important has been the taking of the building occupied by the police headquarters. The first probably to break through."

And on day two of the uprising, the Poles captured the power station and the main post office.

"Our task," says Bokiewicz, "was to cover the attack on the post office with our machine gun against the German bunker which was at the corner of the post office. Our Polish units made a frontal attack from, I think, two or three sides. The battle raged through the night and the post office was taken. Maybe I shouldn't say that, but I was a philatelist at the time so it was very - I had a private interest in the matter as well. The next day, I went to the post office, because I was looking for the stamps, and I found quite a lot of sheets of German occupation stamps and I hid them in the cellar. But of no use because I had to leave them in Warsaw."

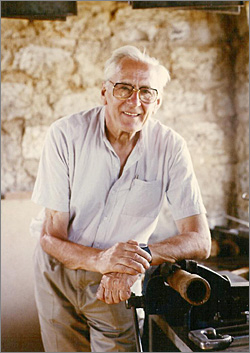

|  | | Waclaw Micuta |

On the same day, a group of Poles in the so-called Zoska battalion captured two German tanks and drove them into action against their former owners. Their target was 'Gesiowka' or the Goose Farm, a transit camp for European Jews on the site of the former Warsaw Ghetto. On August 5th, Waclaw Micuta, a Polish tank commander, charged the wall of the camp

"I am in the tank," recalls Micuta. "We got in front of us the wall with pieces of metal to reinforce the wall and he gave the full speed and our tank started to climb up, climbed up, climbed up, get to the top and whoomph, fell on the other side. It was 40 tons of metal. It was an exceedingly emotional thing because a few hundred of Jews, when they realised that this is not the death but the liberation, you can imagine the emotion of those people. And by God, you know they came to the tank and they embrace us and some of them kneel, you know. And I saw a group of Jews, prisoners, … and there was one of these men and there was one with perfect Polish and a perfect Polish military language. He said, 'Attention,' and then you know he said, 'Lieutenant, I present you Jewish battalion ready to fight.'"

From The Battle for Warsaw:

The German garrison seemed content merely to contain the Poles. No counter-offensive was begun to dislodge them, though when news of the uprising reached Hitler, he ordered that Warsaw Poles be wiped out and their city razed to the ground as an example to the rest of occupied Europe. Heinrich Himmler, his SS Chief, was given the task, but all this was unknown to the Warsaw defenders as they enjoyed a respite in the warm August sunshine. Equally unknown to them, days before the uprising begun, Hitler had decided definitely to defend Warsaw and was rushing there some of his best remaining units. After waiting so long, the dye was being cast for the Poles.

Go to part 3

|