Ashley Smith really liked her English classes in high school. But when she got to college Smith was all business.

"I was really interested in a degree that was going to get me a career in something I thought would be moderately profitable," Smith says. She graduated with a B.A. in marketing and advertising from the University of St. Thomas in St. Paul, Minn. It's a private, liberal arts school with a robust business program.

"I always enjoyed reading and writing in high school but I didn't think an English major would actually get me a job," she says. "Being a writer is great but there aren't that many career paths in it. I wanted something that would be a little more secure."

Smith, 23, graduated in May 2010. The following Monday she was working full time at a for-profit career college in Minnesota.

The liberal arts approach to higher education is uniquely American. And liberal arts programs are under increasing pressure from students like Ashley Smith - as well as parents and policy makers - to show that a B.A. in English or anthropology will be worth the cost. With the U.S. economy struggling to recover from the Great Recession — and with college tuition going up faster than inflation - liberal arts programs face increasing pressure to demonstrate the practicality and relevance of what they teach.

"Today's kids want to know that there will be a job on the other end of college," says John C. Nelson, an expert on higher education at the market research firm Moody's. "This trend is not new, but it's become paramount as the cost of college has risen so fast over the decades."

The overwhelming threat to liberal arts education is cuts in public and private funding to all but the most elite schools, says Brian Rosenberg, president of Macalester College in St. Paul, Minn. "Particularly in education that doesn't have a very narrowly defined vocational purpose. The general economic state of our country — and the priorities that have been defined politically in our country — would seem to weigh against the funding of robust liberal arts education," he says.

A March, 2011 report by the National Governor's Association titled "Degrees for What Jobs?" described the traditional emphasis that colleges and universities place on a broad liberal arts education as an obstacle in preparing a 21st century workforce.

According to the U.S. Department of Education, more than half of all college undergrads now choose business, engineering or nursing. Business is the nation's most popular B.A., at 22 percent of all degrees awarded. Humanities and the liberal arts now account for fewer than 10 percent of all majors — a steep drop from three decades ago.

Some colleges and universities have already made changes they hope will tie Shakespeare and Socrates more closely to 21st century life. They're embracing experiential learning programs - courses where students work to solve real-world problems in local communities - and other new approaches to the four-year bachelor's degree that challenge a model of education that's prevailed for more than a century.

Education experts say elite, private liberal arts schools generally feel the least pressure to change. Selective, sought-after schools with strong endowments can cling more easily to tradition. But colleges lower on the ranking charts - and liberal arts programs at public colleges and universities — are more vulnerable. If they can't attract enough students they can't pay the bills.

In response to the challenges, champions of the liberal arts point to surveys of American employers who overwhelmingly want job candidates with good communication and critical thinking skills. But they also argue that their programs prepare students for a long and rich life of work and learning, not merely the first job after graduation.

In addition, liberal arts advocates invoke national political wellbeing in support of a broad education over narrow career training. "We may be losing one of the great secrets of American democracy: making citizens who can vote, who can dissent," says Leslie Berlowitz, president of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

"A populace that has no education, led by an ideological group of people — whatever their ideology — leads to instability," Belowitz says. "[John] Adams and the founders understood that and they wrote into the earliest documents of this country a wish for broader and broader education."

An American Education

The modern liberal arts college is an American invention with roots going back through the American colonies to England, medieval Europe and finally to ancient Greece and Rome. The actual term is "liberal arts and sciences," and describes the breadth of general knowledge that a well-educated citizen is supposed to possess. The modern liberal arts curriculum includes literature, history, languages, philosophy, mathematics and science.

"Liberal subjects are taught disinterestedly," says Louis Menand, an English professor at Harvard who writes frequently about higher education, "which means that we are open to any kind of inquiry into the areas that we study without regard to any vocational utility, any financial reward or ideological purpose." In other words, it's knowledge for its own sake. Professional or vocational training, Menand says, is seen as "il-liberal." That doesn't mean bad, Menand says, just utilitarian.

In the conventional liberal arts school, a student takes a variety of general studies courses in the first two years, based either on a core curriculum or a set of course distribution requirements set out by the college. After declaring a major, the student spends the second two years taking courses in that chosen field. Some 25 percent of liberal arts major go on to get graduate degrees, according to a Georgetown University study.

"The U.S. is actually quite an outlier compared to most higher ed systems around the world," says David Finegold, dean of the Rutgers University School of Management and Labor Relations, and an expert on workforce skills. In the United Kingdom, for example, students decide their specialty between 16 and 18 years of age, then apply to university in a specific field. "In a way it's a more efficient system in the sense that you're spending less time in [in school] and going right into your specialization, but what I think they lose is the breadth and the preparation for being a well-rounded global citizen," Finegold says.

America's first residential liberal arts college was Harvard, founded in 1693 to train the colonial clergy. Students were drilled in a classical regimen of rhetoric, ancient languages and mathematics. The contemporary liberal arts and sciences curriculum evolved over the 19th century, as colleges added more science classes and reformers complained that the emphasis on ancient languages was impractical. Beginning in 1869, Harvard President Charles Eliot played a prominent role in developing the elective system for undergraduates. He also made the bachelor's degree a prerequisite for professional schools such as law and medicine. Before Eliot, a person could go to law school or medical school without first going to college. Menand says Eliot's reforms influenced many other colleges and universities to change as well.

The liberal arts curriculum spread in the 19th century as church denominations built small, residential colleges across the expanding American landscape. "It was the belief that, in order for citizens to participate in democracy and the civic life that churches wanted, they needed to be educated," says Brian Rosenberg, president of Macalester College in St. Paul, Minn. Macalester was founded in 1874 by Presbyterians. Over the same period, public colleges and universities sprang up to offer new types of training in agricultural, mechanical and other applied fields as well as some degrees in the liberal arts.

Until the middle of the 20th century, higher education was primarily reserved for America's elite. The GI Bill of Rights, passed by Congress at the end of World War II, gave millions of returning veterans a chance at learning beyond high school. The American higher education system rapidly grew to meet the new demand.

"The GI Bill is one of the most important things this country has ever done," Rosenberg says. "[It] was a commitment on the part of the government to provide accessible education to a broad segment of its population, and a belief that the key to both economic and civic success was being educated."

More people were getting diplomas, and those diplomas increased in value. Beginning in the 1970s, a college degree became increasingly important for young people aspiring to a middle class lifestyle. American manufacturing jobs that once required only a high school education started disappearing. Between 1973 and 2007, the total number of jobs in American rose by more than 63 million. But jobs for people with no postsecondary education fell by 2 million, according to a recent Harvard study.

The Vanishing Liberal Arts?

Before the postwar building boom, liberal arts schools made up a greater share of the American higher education sector. Today, the overwhelming majority of college students attend public institutions, including community colleges and public universities. Many of them commute to school while holding down jobs to pay the bills. On-line education is on the rise at schools across the country.

"We still think of college as students sitting on the lawn with a professor talking about Plato." says Anthony Carnevale, an education researcher at Georgetown University. "It hasn't been like that for a very long time."

The 1960s were the high-water mark for people getting degrees in the liberal arts — especially in the humanities (English, history, languages, classics and the like). Since then, the number of liberal arts undergraduate degrees has declined and professionally oriented bachelor's degrees have surged.

"As difficult an economic time as we've been though in the last few years, when a lot of new graduates — not just liberal arts but all majors — are struggling to find jobs, it's not surprising that people are raising questions about whether we are preparing people as well as we could for life ahead and for the labor market," David Finegold says.

Researchers Roger Baldwin and Vicki Baker warn that dozens of liberal arts colleges have either closed their doors or morphed into more vocationally directed programs over the past decade. Of 212 liberal arts colleges identified in 1990 only 137 were still in business by 2009, they reported in an article for Inside Higher Ed. Some failing colleges have been bought out by for-profit institutions looking to acquire those schools' accreditation — a necessary benchmark to qualify for some government-funded student loan programs.

What many other small liberal arts colleges have done is become small universities, says John C. Nelson of Moody's. They've added vocational undergraduate and graduate programs such as business, nursing and education.

"These are typically low-cost programs to offer and are in high demand," Nelson says. "And many schools can offer part time programs for working adults." The professional programs subsidize the liberal arts at these schools, Nelson says. He predicts that non-selective schools that fail to diversify this way will continue to close their doors.

Plato and Practicality

The economic and competitive pressures on liberal arts colleges — and liberal arts programs within public universities — have led an increasing number of schools to experiment with new ways of teaching and learning. Some have joined a consortium of colleges called Imagining America to create partnerships between local community groups and arts and humanities departments to work on real-life problems. Project Pericles is a nonprofit that bands colleges and universities together to promote social responsibility and active citizenship as essential elements of their educational programs.

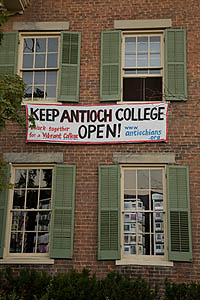

At Portland State University in Oregon, seniors in the liberal arts-oriented University Studies program take "capstone" classes that mix academic work with community service. At Berea College in Kentucky, all students have on-campus jobs that help pay their tuition and are meant to instill good work habits. Antioch College in Ohio requires students to alternate terms on campus with paid or volunteer work in the professional world. Meanwhile, some for-profit colleges and universities are modeling radical new ways to teach the liberal arts.

Writing in the publication Liberal Education, former Northeastern University president Richard M. Freeland described the trend of "connecting ideas with action" as a needed and "revolutionary" phase of experimentation in the American academy. But higher education expert Kevin Carey at the Washington, D.C. think tank Education Sector is skeptical of how much of a groundswell the new practicality represents. "I don't know if I'd say it's a movement," Carey says.

Carey is also concerned about what he says is a lack of good research on what really works to prepare college students to be effective workers and citizens. "As much as our colleges and universities are institutions that are dedicated to inquiry, they're not all that interested in inquiring about themselves," Carey says. "The focus of all that intellect tends to be outward and not inward."

Macalester College President Brian Rosenberg says there may be fewer traditional liberal arts colleges in the future. But he's bullish on the value of a liberal arts degree in the rapidly-changing global economy.

"I don't think we've delivered an effective message about a liberal arts education," Rosenberg says. "I think we've been somewhat squeamish in talking about its practical utility." He believes an English or a history major may be more practical, in the long run, than a business or accounting degree.

"We know now that the typical student who graduates college today will not just change jobs but will change careers multiple times during the course of his or her life," Rosenberg says. "So the notion that you're training students to be creative and flexible is ultimately a very practical notion. We need to teach the skills needed so that our graduates can handle any job thrown at them."