|

| ||

|

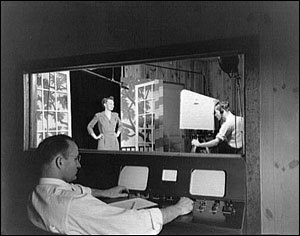

Sex, Race and Rock & Roll part 1, 2  Early television control room and studio - Courtesy Library of Congress "When television surfaced, everybody said 'Wow! Things are going to be really fantastic, but guess what? Radio is now dead!'" says Dr. Rick Wright from Syracuse University, communications professor, DJ, radio historian. "There were folk who showed up to do their radio shows, without warning found a note on the door that the show had been cancelled and moved over to television. All the advertising, all the money, everything went over to television." Wright says the networks more or less just abandoned the medium. They sold off stations, they reassigned employees. And with the networks out of the game, small business people could step in and buy up these abandoned stations and licenses. These small local operations couldn't afford Bing Crosby or Arturo Toscanini and the NBC Orchestra, but there were local artists in places that were off the cultural map in the network era. "You go into the South and you go into the Mississippi Delta and wonderful places like that," says Wright. "We find many of the American blues artists, Howling Wolf, Jimmy Reed, playing some heavy music. But they were calling all of this music race music at the time and basically it had no outlet." And now it did. Stations around the country found that the radio business could be cheap. You could get a local band to play for nothing, maybe just a plug for their show at the roadhouse later that night. Better yet, you could just play records. Find a good personality to play those records and shill for local companies and you were making money. Dewey Phillips was on the air in Memphis around 1950. He was an anomaly at the time: a white DJ spinning regional rhythm and blues hits for black audiences. Rick Wright says Phillips and his African American contemporaries up the dial on Memphis' WDIA helped elevate disc jockeying to an art form. People like Nat Turner, a young B.B. King, and, one of Wright's favorites, Rufus Thomas. "Now, Rufus comes in, 'Hey baby, this is Rufus Thomas, WDIA Memphis, Tennessee, where you can cop a smile about a quarter mile provided you've got time and don't mind this drive time line we're gonna try.' Wright says that one Nashville station, WLAC Nashville was owned by the Life and Casualty Insurance Company - L-A-C. He says that that station would take this music and this DJ style to places it had never been. He says the course of American cultural history was changed one Saturday.  Gene Nobles, DJ for WLAC, created one of the first mainstream R&B formats on a major radio station. - Courtesy tktktk The story goes like this, a white DJ named Gene Nobles was doing his show. "And they were playing, basically, records by Guy Lombardo or whatever and it was that era of a 50,000-watter trying to find itself with no audience," says Wright. "And there were some African American students from Fiske University who had gotten past the security and got up to the station and brought a bunch of 78s with them." And they walked into the studio and started talking to the DJ. "Mr. Nobles, can you play some of our folks' records on your radio show?" And Nobles said sure, hand them over. Records of Fats Domino and Little Richard, Chuck Berry and Etta James, Laverne Baker. And he played them. "All of sudden," says Wright, "the phone started to ring, and the letters and cards were coming from all over the place. And they established that night, one of the real, first, mainstream R&B formats on a major powerhouse radio station. WLAC 1510 Blues Radio Nashville, Tennessee. The only full time R&Ber at night with 50,000 watts." At night, 50,000 watts get you very far. Bob Dylan has said he owes much of his musical inspiration to listening to WLAC as young teenager all the way up in Minnesota. And DJs in other cities were picking up the WLAC style. In Cleveland, Alan Freed helped spread the gospel of R&B and African-American style to young, white America. He popularized the name rock and roll along the way. Over the course of a few years the music crept up the charts and into mainstream consciousness. Bruce Morrow remembers sitting around his living room in Brooklyn as a teenager listening to a countdown program hosted by a stodgy announcer named Morton Block. "At that time," recalls Bruce Morrow, "'On the Radio with Morton Block,' the number 20 record would be Doris Day and then it would be Victor Moon and Frank Sinatra. And all of a sudden rock and roll started rearing what he called 'its ugly head' into his top 40 countdown." By early 1955, this music was a cultural force. And a guy polite society saw as a renegade had reached the big time: Alan Freed was on the air on one of New York City's most popular stations. It's almost hard to imagine it actually happened. The stir that rock and roll caused is so well documented in movies and pop culture. People burning Elvis records. A nation seemingly terrorized by its teenagers. It's such a symbol of the repressed, paranoid, square, Eisenhower era, it's hard to remember that in 1955, the feelings were raw and this moment was powerful. Irving Caesar, lyric writer and music publisher, (he wrote Tea for Two) made his opinion known during a "radio town hall meeting." "Parents have a right, because they sense not the content but the intent," said Caesar. "The leering clarinet, the moaning, sensuous trombone. It's interpretation. The very fact that it appeals to a certain kind of interpreter. For instance … if I say, 'I love you truly' and weave my eyes and twist my body when I say it, 'I love you truly'. You know what I intend to convey when I say 'I love you truly' that way." And it is also clear what he intends to convey when he says this. "You know the rock and roll business, it was born out of rhythm and blues and race. Written by people who didn't know the English language. Didn't know how to spell, didn't know how to play but could accompany himself on the gee-tar and so forth and that's how rock and roll was born." Continue to part 2 |

||