Idalia Fernandez and George Cushman

By Ellen Guettler

Idalia Fernandez's framed college diploma hangs on the wall in her mother's Florida home.

Fernandez says she spent late nights studying and worked to pay her tuition - she earned the degree. But her mother made it possible. She brought the family to the United States from Honduras. She had only a fifth grade education. She cleaned houses and worked retail to keep the family afloat.

In return, Fernandez wanted to make her mother proud.

Fernandez's voice still trembles when she remembers the day she got her diploma.

"I just felt like I had broken through something," she says. "I broke down. I gave it to my mom and said, 'This is for you.' So it's framed in her house, not mine."

Fernandez went on to be a financial analyst. There were no other Latinas in her professional circle. Others hadn't broken through as she had. Fernandez felt like her success came with a responsibility.

"If I had figured it out on my own with little resources, with little knowledge, but all the love and support from my family, then I had an obligation to go back and help others do the same," Fernandez says.

She started working for the Hispanic College Fund (HCF), an organization that encourages Latino students to go to college and become professionals. She is now the organization's president.

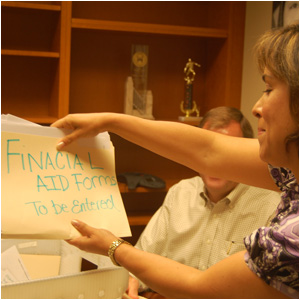

The HCF runs a $2.2 million annual scholarship fund for Latino students.

It also runs a four-day symposium where students are drilled with the importance of a degree. There's a ton of information about financial aid, since the average family income of an HCF student is just over $20,000 a year. Students are also matched with mentors so they can see people like themselves who are making it.

HCF administrators say most of the students they work with do make it through college. But they're bucking a national trend.

Young Latinos are the fastest-growing segment of the population, but they're the least likely to have college degrees. Thirteen percent of Hispanics in the United States have a bachelor's degree or higher, compared to 53 percent of Asians, 33 percent of non-Hispanic whites and 20 percent of African-Americans.

These numbers worry George Cushman. He works with Fernandez at the Hispanic College Fund as the vice president of programs.

"We're in a lot of trouble in the country because the number of white professionals leaving the work force is so large," Cushman explains. "The largest population to replace them, the fastest-growing youth population, are Latinos. And they're getting degrees at a third the rate. This creates a vacuum that is going to result in a lessening of the security and the economy in the country."

Cushman's college diploma isn't on his mother's wall. He thinks it's stored away in a closet. That's because his graduation was no big deal to him. He assumed he'd get there.

"My family's been in this country for a long time," Cushman says. "I'm white. I've never had a question that [somebody] believed in me. Everybody looked at me and said, 'Of course, he's going to be very successful.'"

But the students targeted by HCF programs don't enjoy the same certainty. In addition to the cost of college, these students have to contend with language barriers, discrimination, family pressures, and their own expectations of what they can and should achieve.

HCF tries to tackle all of these things. And the strategies they use to motivate students might not be what you'd expect.

Other programs for high school kids tout the higher earnings college graduates make. A degree can lead to a big house and big car in the student's future. But when they first started running the college symposium, Cushman and Fernandez quickly learned that this was not a successful pitch to Hispanic young people.

"When we first did this," Cushman says, "we looked at the students and they were looking at each other saying, 'How do I explain this to my parents? My house isn't good enough? The car isn't good enough? They're working two jobs, each of them. They're killing themselves and it isn't good enough?'"

Fernandez says the best motivator for their students is the desire to help their own community.

"They all want to give back in some significant way," Fernandez explains. "They want to change their world. And so the appeal is, you can do that with a college education."

She says many students have grown up in poor neighborhoods. They've seen gang violence, suffering and injustice. These experiences motivate them.

"If you go to a hospital and you saw that a family member didn't get the health care they needed because someone didn't understand their language and dismissed them, then you're the one that needs to become the health care provider who's bilingual and who's going to serve the Latino community," she says.

HCF students say getting an education is the best way to repay the debt of gratitude they feel toward their parents. It's the same feeling Idalia Fernandez had when she received her diploma at her college graduation.

And George Cushman says he's moved by that spirit of giving back.

"That is what America is all about," Cushman says. "[I]t's truly an American way of doing things."

Back to Rising by Degrees.