Mario Martinez

Mario Martinez never liked school.

"Middle school and high school was a lot of getting in trouble," he says. "I had a lot of absences. I went to a lot of parties instead of school. My friends were smart but nobody would actually do the work. We was the bad crowd."

Mario grew up in Langley Park, Maryland, just outside of Washington, D.C. "It was very noisy," he says. "We would hear police every night, we'd hear gun shots, we'd hear people scream."

Mario lived in a small apartment with his three brothers, his mother and his father. Other relatives stayed there too. "We was always squished up," Mario says.

Langley Park is a small, crowded area with a largely Hispanic population. A lot of people from El Salvador live there - it's home to the largest percentage of Salvadorans of any place in the United States.

And the notoriously violent Salvadoran gang MS-13 is everywhere, says Mario.

"It's kind of shocking, I guess, when I think about how we grew up. We didn't think we were capable of doing something good in life. We always thought that we was going to end up in the street. We didn't have any goals for life. We didn't think about our future much."

Mario says he dropped out of school in 9th grade. He went to night school for a while, then started 10th grade at another high school. But he only lasted two months. He says he was kicked out just days before his 16th birthday. He got a job as a cashier at Whole Foods.

"Man, I had no plans of my future at all," he says. "I don't know what I was thinking. I was completely lost. I just know I was going to grow old. And that's basically it."

Mario's a college student now. He goes to Montgomery College, a community college in Maryland just a few miles from where he grew up.

I met him in a writing class. I knew nothing about his past, what it had taken for him to get here. It was the summer of 2008. Mario was 19.

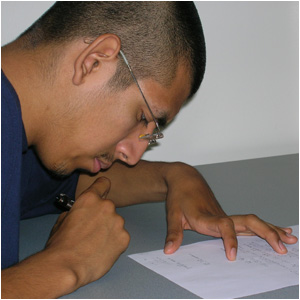

The class began with a writing warm-up. The assignment - to write about a job you really hated. The students get five minutes to write. Then the professor puts them in small groups and they read their writing out-loud.

"The job that I can say I really disliked or hated was in Fair Oaks, Virginia," Mario reads.

Then he looks up. "Oh," he says to his group. "I didn't put what it was. It was valet parking."

He looks down at his paper again and continues to read. "I really don't know what I was thinking. I left a job at a grocery store to go park cars. At first I thought it would be kind of cool. I thought about how I would be able to drive all the nice cars that come out on the commercials. Reality kicked in after the first day. I had left…" His voice trails off. He looks up. "That's all I got," he says.

This is English 001. It's a "developmental" writing class. That's another way of saying it's remedial level; the students in this class need help with basic skills like writing paragraphs, using punctuation, understanding grammar. This is what they didn't learn in high school - or middle school, for that matter.

The students were placed in this class based on the results of a test they took when they enrolled at Montgomery College. All entering students have to take this test. And most of them need some sort of remedial class. Across the country, more than 60 percent of community college students have to take at least one remedial class before they can take college level courses. So Mario and his classmates aren't really in college yet. They're paying to take high school again.

"He likes to sit by the window when Ralph takes the train to Philadelphia." Mario's small group has moved on to grammar exercises. The woman sitting next to him is reading from a worksheet, trying to fix the errors in a sample sentence. "Ralph takes the train to Philadelphia so…" she says. "No, no, no, that doesn't make sense."

Mario pipes up. "When Ralph takes the train to Philadelphia, he likes to sit by the window."

"Yeah," says the woman next to him. "That's how I was trying to say it. I know I'm not stupid."

Mario smiles at her. He has a big, friendly smile. I notice this about him right way. His dark hair is cropped short. He's thin, with long arms and big hands. He's wearing rimless glasses, a turquoise golf shirt, and jeans. He looks bookish, nerdy even. It's hard to imagine him as the thug he says he was - but I don't know that about him yet.

I'm in this class to find students willing to be interviewed about their experiences in community college. I don't get many volunteers. So I ask the professor if she can ask a few students directly on my behalf. She recommends Mario. She says she doesn't know much about him, but he seems to be trying to change his life.

A few days later I get this e-mail from him:

"I recieved your card from my teacher today. I dont have internet access at home. my teacher told me you wanted to speak, or interview. I am fine with that. I will check my email when I am on campus. if any questions feel free to ask. I dont know what the process is, so you are going to have to guide me thru it a bit if thats ok. thank you, have a good day."

Mario was born in Washington, D.C. His father was born in El Salvador, his mother in Guatemala. She cleans houses for a living. His dad is dead.

He was killed in a car accident in 2005. "He was dropping my mom off at work and on the way back home he flipped over. He was in the hospital for like three to four days, I believe. And he passed away."

Mario never got to visit him in the hospital because he was in jail at the time. "Everything happened in 2005," he says. "2005 was bad."

Not long after Mario dropped out of high school, he was arrested along with several suspected gang members. He was sixteen years old. He was picked up in connection with a drive-by shooting and charged with attempted murder. He spent seven months in jail. And then, "one day they just told me to pack my stuff and go home," he says.

The case never went to trial. It's not clear why it didn't. A search turned up no public records on the case. Mario says the charges were dropped. "I don't understand exactly what happened."

And when he came home, everything was different.

His father had a small life insurance policy and shortly after Mario got out of jail, his mother spent it to get her family out of Langley Park. She bought a house in a middle-class neighborhood in nearby Silver Spring.

"It's a different world basically," he says. "It's quiet at night. To me it was kind of creepy because I never slept in a quiet neighborhood. I couldn't sleep the first couple of weeks."

He says he didn't know what to do with himself during the day. He would get up in the morning and just walk around the neighborhood, maybe go to the 7-Eleven store down the street. That's what he knew how to do - hang out, walk the streets. He says the neighbors seemed scared of him. And he doesn't really blame them. In fact, he remembers thinking to himself - maybe I will ruin the neighborhood. Like, here comes Mario Martinez, there goes the neighborhood.

But he hasn't ruined the neighborhood.

He says the neighborhood has changed him.

Mario says if his mother had stayed in Langley Park after he got out of jail, he would have been back on the streets.

Eventually, he says, "I would have gone back to jail. And then they would have sent me to prison." He pauses. "Yeah, I'm almost for sure about that."

But being in a middle-class neighborhood, away from the crime and chaos of Langley Park, made all the difference for Mario. He says somehow he knew not to seek out his old life again. Besides, he says, none of his old friends were there anymore. They're all in jail or prison.

All of them? I ask.

Yeah, he says. All of them. And they're still there. His older brother too.

There was nothing to go back to in Langley Park. His old life was gone.

So Mario went back to work at Whole Foods, then parking cars. And then he got a job with a contractor installing wood floors.

"I still wasn't convinced about school," he says.

But the job got him thinking. "I would leave the house around 6 in the morning and sometimes come home at 11 at night and had to do the same thing over again the next day."

He was worn out. And he remembers watching his boss, a man in his 40s with children at home. He worked long hours too, didn't have time for his family. "So I started thinking, when I get old, am I going to be the same way? Am I going to be in the same job, doing the same thing, living his life?"

He says he started thinking about the future for the first time. And wondering - what are the other options? He really had no idea, no role models.

So Mario started asking the people at the houses where he installed floors. "We would go to a lot of big people's houses, like mansions, and I started asking a lot of them what did they do, like what was their career? They wouldn't want to tell me what they was working in but they would tell me they got there because of school."

Mario had earned his high school equivalency - his GED - in jail. He says he did it because he was bored. So with that under his belt, the next step was college. He started asking around, trying to figure out how people get to college. And everyone he asked told him: Go to MC. That's Montgomery College. They said anyone can go, all you have to do is sign up. So he did.

"I don't know what I want to do or what I want to be yet," he says. "This is basically my first step to doing something new."

In the beginning he wasn't sure about his decision to go to college.

"The first day it was really hard and we got loads of homework," Mario recalls. "And I got home and I was like 'Ah, I don't want to do this.'"

But then he started thinking about how he always sets himself up for failure. And he thought about something the teacher told the class. She said the only way to do school is one day at a time. Come to class, do the homework, come to class again.

"Now it's not that hard," he says. "I just go home and take a quick nap and do some homework."

Mario is taking one class. He says he's not ready for more. And he needs to work - to help his mother with the mortgage, and pay tuition. It's about $660 per class, plus books.

But so far, he can't find a job. He quit installing floors because he says there was no way he could do that and go to school at the same time. The hours were not only long but also unpredictable. If the boss says you have to stay late, you have to stay late.

When I first interview Mario, it's July 2008. He's about halfway through the summer English class - his first at MC - and he's not sure what he's going to take next.

I ask him if he has ever been to the advising office to talk with a college counselor and he says no, he signed up for the class on-line. I ask him if he's planning to go see a counselor and he nods yes and I say, "Want to go right now?" and he looks at me wide-eyed, shrugs, and says "Yeah."

So we walk across campus to the student center.

The advising center is crowded. The man at the front desk tells us it's a 20-minute wait. We sit down.

Across from us is what appears to be an entire family, speaking a language I don't recognize. I think they're from Africa. There's a man, a woman, a couple of teenagers, a toddler and a baby. It seems they are waiting to sign someone up for school.

They're a sharp contrast to Mario, alone. I ask him if he ever had a teacher he liked, a counselor or mentor who helped him out, encouraged him in school. "Um," he says. "No."

But later he remembers there was one person.

"We used to call him Mr. Chulo," Mario says, laughing. "Chulo is like a Spanish word for handsome or slick."

"Mr. Chulo" was a security guard at his high school. "He always tried to tell me to stay out of trouble," says Mario. "He'd see me in the hallways and see me skip class and he always stopped me and instead of getting me in trouble he would just give me advice. He would tell me I gotta fix things up," he says. "I didn't listen to him."

We get called into an adviser's office.

"OK, um, this is my first time here," says Mario.

The adviser stops him and smiles. "Hi," she says, extending her hand. "I'm Terri Bailey."

"Sorry," Mario says, realizing he didn't introduce himself. "I'm Mario, and basically I don't know what classes to take in the fall. I don't know what the process is."

Bailey looks up the scores Mario got on the placement test he took when he enrolled at MC. Turns out he did well enough that he doesn't have to take remedial reading and math classes. So if he passes his writing class with at least a B, he's ready for college-level courses.

Mario is shocked. The last math class he remembers taking is pre-algebra in 9th grade, and he says he slept through most of it. But the test results show he's ready for intermediate college algebra.

"So tell me," says Bailey, "in terms of your goals at Montgomery College, what direction do you think you're going to move in with your studies?"

"I have no idea," says Mario. "I'm taking general studies to see what I like."

Bailey encourages him to think about whether he will be doing liberal arts or science because that affects what kind of math class he should take. Mario looks kind of blank, confused. Bailey keeps pausing, leaning in a bit, like she's trying to figure out if he's following her.

She seems not to know quite what to make of him.

At first she thought he wasn't a native English speaker - that's what prompted her to look up his test scores right away. She was trying to figure out if he had taken the right placement test - there's one for English speakers, another for people who come from other countries. And when Bailey saw Mario's reading score, she was visibly surprised. He did well.

But it's not a shock she wasn't sure about his English language skills. He's barely saying anything.

"Questions?" Bailey asks.

"No, uh-uh," says Mario, shaking his head.

"Is that it for you?" she says.

"Yeah."

"You sure?" She leans in. "Are you clear?"

"Yeah," he says. "Thank you."

And we leave.

Mario will be back again in a few weeks, once he finishes his English class. He has to know his final grade before he can sign up for the next class. I encouraged him to come to the advising center too early.

"That's OK," he says. "That was good for me."

We walk outside. It's a swampy hot day, the air is muggy and thick.

Mario says he's going home to meet his little brothers. They're mowing lawns right now. When they're done, Mario is taking them to the pool.

Continue to part 2.