For more than a quarter-century, the 46-year-old Jerry Gober has been in the cabinetmaking business. He proudly shows off his busy woodworking shop in suburban Sugar Hill, Georgia, where he employs fifteen people making cabinets and shelving for homebuilders around Atlanta.

| |

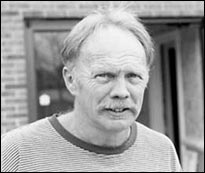

Jerry Gober, a Gwinnett County cabinetmaker, was arrested in a reverse sting. Photo: John Biewen |

Gober insists he's never sold drugs. He does have a history of marijuana use and addiction to methamphetamine. But as a condition of his divorce in 1996, Gober had to take monthly drug tests in order to visit his children. He'd passed one on the morning of his arrest. He'd been clean for several months, he says. "It wouldn't have happened. I wasn't out looking for drugs that day."

But Gober's girlfriend at the time, Yvonne, called him and urged him to buy some meth for both of them from a dealer she knew. Gober and Yvonne were having a rocky time. What he didn't know was that she'd gone to the Gwinnett County police and offered to act as a paid informant.

"We weren't getting along that good and she didn't get along with the kids too good. I told her she had to move out and that pretty much made her mad. I guess that's what made her decide to try and get me in trouble."

Yvonne was helping the police set up Gober for a "reverse sting." In a traditional drug sting, undercover cops pose as drug buyers to bust a dealer. In a reverse, the cops become the seller and arrest the buyer. Reverse stings used to be rare; even now, not all police departments do them.

Attorney Donn Peevy heads the law firm representing Gober. In a former life in the 1970s, Peevy worked undercover drug cases as an officer with the Gwinnett County police. He recalls the first time he heard of reverse stings, in a discussion with the local district attorney.

"He said 'I've heard that in some of these states and in some other jurisdictions, they're doing reverse stings where police are selling drugs,'" Peevy recalls. "He told [those of] us in the vice squad then, 'Don't do it because I'm not going to prosecute it. Particularly if these people are addicted, they're easy targets and they can't help themselves. We could do them everyday and fill up the jails, but we wouldn't be stopping the problem with drug abuse and drug use.'"

Police departments started doing more reverses after asset forfeiture came into vogue in the 1980s. The traditional sting has no payoff; the police seize drugs and destroy them. In a reverse, the target brings cash the police can seize.

Now, back to our story. Jerry Gober's girlfriend, a police informant, calls him about a meth connection. "She told me that it was her cousin that had it," Gober says. He recalls Yvonne's initial offer was two ounces of the drug, though he says he can't remember the asking price.

Gober said no — three times. Yvonne kept calling back, lowering the amount of methamphetamine and the price. "And then the fourth time she called back, it was an ounce for a $1,000, which I think is probably half price," Gober says.

The Gwinnett County Police say a $1,000 for an ounce of meth is not a bargain; it's the going rate for traffickers. Gober says he'd never bought a whole ounce before that day. In any case, he gave in — to his girlfriend's pleading, he says, and to his own addiction. He got a $1,000 cash and went to meet the dealer — actually an undercover cop — in the parking lot of a local K-Mart.

A police video of the "take-down" shows Gober climbing into the detective's SUV and asking of the meth, "Is it pretty good?" Gober hands over his fistful of cash. Two vehicles pull up and four officers jump out shouting, "Don't move — police!"

The police arrested Gober and seized his SUV and his money. They first charged Gober with trafficking because he'd tried to buy an ounce of meth — a trafficking amount under Georgia law. If convicted on that charge Gober would have gone to prison for ten years. But he got lucky. Some of the powder spilled during the arrest, so the district attorney — fearing trouble in the courtroom over the alleged ounce — reduced the charge to possession. Gober spent just 30 days in jail and a year in house arrest. Because of technical mistakes by the police he even got his car and his $1,000 back.

Still, Gober and his lawyers argue that the Gwinnett County police, motivated by asset seizure, created a crime.

"I admit I shouldn't have been there to start with," Gober says. "I made a mistake. But after they called the first time and I said no, I think that should have been it. I don't think they should have pushed it, especially the second and third — you know, they called me four times before I said yes."

Gwinnett County law enforcement officials defend Gober's arrest as good police work. They argue Gober's hesitancy to make the buy was standard negotiation that comes with any drug deal. The fact that police created an opportunity for Gober to break the law doesn't make him any less guilty, says Gwinnett County District Attorney Danny Porter. "If you possess a controlled substance, if you sell it, if you manufacture it, if you possess it with intent to distribute, you're in violation of the law. Period. That's it."

Gwinnett is a large and fast-growing suburban county with a lively drug trade, police say. The local police seize, on average, $600,000 in cash and vehicles every year. Porter insists the police would do reverse stings even if the operations didn't yield cash for the department. Then again, he concedes the promise of asset seizure makes reverse stings affordable. "Because when you pretend to be a drug dealer, you've got to pretend all the way and you've got to show up with all the toys," Porter says. If not for the forfeiture statues, he adds, it would be hard for the head of the narc squad to "go up to the Chief of Police and say, 'We need to rent a fancy SUV for this case that is not going to — that's going to net us an arrest.' I suspect we'd have a harder time with that. So certainly forfeiture has some inducement, but we don't do it just for the money."

Next: Fueling the Drug War