Ossie Davis

(1917 - 2005)

"Eulogy for Malcolm X"

Faith Temple Church of God In Christ, New York City - February 27, 1965

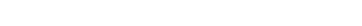

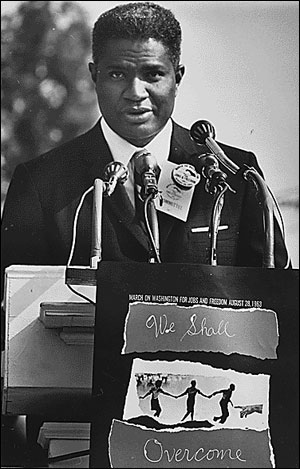

Ossie Davis

Actor Ossie Davis and his wife, Ruby Dee, were so deeply involved in the freedom struggle of the 1950s and 60s that they have been called "the first couple of the civil rights movement."1 They took part in countless fundraisers and demonstrations. They were recruited to emcee the 1963 March on Washington. And they were friends with many of the movement's leaders, including Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X. Davis was an accomplished writer as well as an actor, and he was called on to eulogize Malcolm X after he was assassinated. Davis decided to speak at the funeral for the controversial Malcom X in spite of the damage it might have caused his mainstream acting career. Davis's eulogy would be among the most memorable words he ever wrote.

Ossie Davis was born in the small town of Codgell, Georgia. His birth name was Raiford Chatman Davis, but a clerk at the local courthouse misheard his mother speak his initials, R.C., and marked him down as "Ossie." In an autobiography, Davis explained that the clerk was white, and in Jim Crow Georgia his mother did not dare contradict him. The name stuck.2

Davis got his own lesson in the realities of discrimination when he was a small boy. Davis's father, Kince, helped build and maintain a short-line railroad owned by a local white land baron named Sessoms. The line carried timber and livestock on a 23-mile stretch to a town in the next county. On several occasions, Ku Klux Klansmen warned Davis's father that the position of crew boss was white man's work. But Kince Davis had a pistol in his belt and the protection of his powerful employer. "The Klan never came," Davis recalled. "A black man with Daddy's skill was a rare and precious commodity to Sessoms and the other big men who ran things. They didn't mind giving him a white man's job as long as they didn't have to give him a white man's pay."3 Seeking greater independence, Kince Davis later quit the job to start his own herbal medicine business. For the rest of the time Ossie lived with his parents they struggled to get by.

Ossie Davis was the oldest of five children. His parents could not read, but they were enthusiastic storytellers. As a schoolboy, Davis consumed books with a ravenous hunger and dreamed of becoming a writer. He began acting in plays and operettas in high school. After graduating in 1934, Davis hitchhiked to Washington, D.C. to live with his aunts and attend Howard University. He came under the influence of professor Alain Locke, a writer and philosopher whose anthology The New Negro was a defining text of the black artistic and intellectual movement known as the Harlem Renaissance. Locke encouraged Davis to pursue formal training as an actor. Davis dropped out of Howard after his junior year and moved to Harlem, where he worked odd jobs and sometimes slept on park benches while learning the theater trade.

After serving in World War II, Davis landed the lead role in the 1946 Broadway play Jeb, about a disabled veteran in racist Louisiana. The play was a flop, but it established Davis as an actor to watch. It also introduced him to actress Ruby Dee; the couple married two years later. Davis and Dee appeared together in numerous theatrical, film and television productions, including Lorraine Hansberry's groundbreaking play A Raisin in the Sun and several films by Spike Lee. Meanwhile, Davis wrote his own plays, including Purlie Victorious, which opened on Broadway in 1961 with Dee in a starring role. Purlie is a comedy about racial stereotypes centered around an itinerant black preacher who tries to start an integrated church. It was turned into a movie, and then returned to Broadway as a hit musical.

Davis also worked as a movie director, creating one of the first successful "blaxploitation" films of the 1970s, Cotton Comes to Harlem. Blaxploitation was a genre of streetwise urban movies aimed at African Americans. It generally featured black heroes outwitting white villains to a soul and funk soundtrack.

In 1995, Davis and Dee were awarded the National Medal of Arts. In 2004, they were jointly recognized at the Kennedy Center Honors for their artistic achievements, and for breaking open "many a door previously shut tight to African American artists."4 In February 2005, Davis was acting in a film being shot in Miami when he died of natural causes in his hotel room. He was 87 years old.

Davis and Dee met Malcolm X in the early 1960s. Dee's brother was one of Malcolm X's disciples and introduced them. They became friends. Most of Malcolm X's followers were the common folk of Harlem, and Malcolm's fundamentalist religious beliefs, as dictated by the Nation of Islam, disapproved of the theater. But historian Peniel Joseph says the Broadway actors became Malcolm X's gateway to New York's radical black intelligentsia. "Davis and Dee formed this core group of second-tier celebrities who served as sounding boards, secret fund-raisers, and trusted confidants for much of Malcolm's career," Joseph writes.5 Meantime, they were also firm supporters of Martin Luther King Jr. Davis marched with King during civil rights demonstrations in the South.

Supporting Malcolm X involved professional risk for mainstream performers like Davis and Dee. "He was saying some pretty rough things, especially about whites," Davis told an interviewer. "Some of us, you know, had our jobs out in the white community – we really didn't want to get too close to Malcolm."6 Still, Malcolm X was a frequent guest at the couple's home in the suburbs of New York City. "Malcolm…was refreshing excitement," Davis later explained in the magazine Negro Digest. "And you always left his presence with the sneaky suspicion that maybe, after all, you were a man!"7 Malcolm X visited Davis in the last week of his life. He talked about his break with the Nation of Islam and the firestorm that ensued. "Malcolm at the end was a hunted and haunted man," Davis wrote. "Running for his life; his home firebombed." 8

Malcolm X was shot to death on February 21, 1965 as he prepared for an indoor rally in New York. His pregnant wife and four children witnessed the killing. Three members of the Nation of Islam were convicted and sent to prison for the murder. When Davis and Dee heard the news of Malcolm X's assassination, they drove to Harlem and walked the streets through the night, talking with the gathering crowds about the killing. "The situation was hostile and explosive," Davis wrote.9

Harlem was full of riot police and threats of violence. The mosque where Malcolm had preached was firebombed. Given the risks, Malcolm's supporters had a hard time finding a venue for the funeral. They finally secured the Faith Temple Church of God in Christ. Malcolm X's lawyer, Percy Sutton, approached Davis to give the eulogy. Davis was the choice of Malcolm X's widow, Betty Shabazz. Davis was surprised by the request – he'd been Malcolm's friend but was not a Muslim. Sutton explained that Davis was widely respected and could help keep the peace. "You're the least controversial person we can think of," Davis recalled Sutton telling him. "The Muslims would accept you. The left wing will accept you. The right wing will accept you. The black folks will accept you. The white folks will accept you. So you're it." Davis agreed.10

The funeral took place on Saturday morning, February 27, 1965. Looking out over the casket, Davis reminded the mourners of Malcolm X's deep commitment to Harlem and its African American citizens. He recalled the pride and determination that the powerful orator could stir within his people. "Malcolm was our manhood, our living black manhood!" Davis declared. He concluded the eulogy with words that would be repeated often over time: "We shall know him then for what he was and is – a prince, our own black shining prince, who didn't hesitate to die, because he loved us so." 11

Listen to the speech

Here—at this final hour, in this quiet place—Harlem has come to bid farewell to one of its brightest hopes—extinguished now, and gone from us forever. For Harlem is where he worked and where he struggled and fought—his home of homes, where his heart was, and where his people are—and it is, therefore, most fitting that we meet once again—in Harlem—to share these last moments with him.

For Harlem has ever been gracious to those who have loved her, have fought for her and have defended her honor even to the death. It is not in the memory of man that this beleaguered, unfortunate, but nonetheless proud community has found a braver, more gallant young champion than this Afro-American who lies before us—unconquered still.

I say the word again, as he would want me to: Afro-American—Afro-American Malcolm, who was a master, was most meticulous in his use of words. Nobody knew better than he the power words have over minds of men.

Malcolm had stopped being a Negro years ago. It had become too small, too puny, too weak a word for him. Malcolm was bigger than that. Malcolm had become an Afro-American, and he wanted—so desperately—that we, that all his people, would become Afro-Americans, too.

There are those who will consider it their duty, as friends of the Negro people, to tell us to revile him, to flee, even from the presence of his memory, to save ourselves by writing him out of the history of our turbulent times.

Many will ask what Harlem finds to honor in this stormy, controversial and bold young captain—and we will smile. Many will say turn away—away from this man; for he is not a man but a demon, a monster, a subverter and an enemy of the black man—and we will smile. They will say that he is of hate—a fanatic, a racist—who can only bring evil to the cause for which you struggle! And we will answer and say to them:

Did you ever talk to Brother Malcolm? Did you ever touch him or have him smile at you? Did you ever really listen to him? Did he ever do a mean thing? Was he ever himself associated with violence or any public disturbance? For if you did, you would know him. And if you knew him, you would know why we must honor him: Malcolm was our manhood, our living, black manhood!

This was his meaning to his people. And, in honoring him, we honor the best in ourselves. Last year, from Africa, he wrote these words to a friend: My journey, he says, is almost ended, and I have a much broader scope than when I started out, which I believe will add new life and dimension to our struggle for freedom and honor and dignity in the States.

I am writing these things so that you will know for a fact the tremendous sympathy and support we have among the African States for our

human rights struggle. The main thing is that we keep a united front wherein our most valuable time and energy will not be wasted fighting each other.

However we may have differed with him—or with each other about him and his value as a man—let his going from us serve only to bring us together, now.

Consigning these mortal remains to earth, the common mother of all, secure in the knowledge that what we place in the ground is no more now a man—but a seed—which, after the winter of our discontent, will come forth again to meet us.

And we will know him then for what he was and is—a prince—our own black shining prince!—who didn't hesitate to die, because he loved us so.