|

| |||||

|

Millions of people work on the fringes of the debt and credit industries, profiting as Americans rack up record amounts of personal debt. They will cash your paycheck when the banks turn you away. They will trade your car title for a short-term loan. They will rent you furniture if you can't afford to purchase it outright. And they will come calling when you fall behind in your bills. No credit? Bad credit? Read the profiles below to meet some of the people you may be keeping in business. The Debt Collector, The Check Casher, The Repo Man THE DEBT COLLECTOR

"By the end I was like, 'Pay your bill, grandma!'" she jokes holding her hand to her ear like a phone. Salminen recently left debt collections after three years in the business. She says the thousands of phone calls to delinquent debtors left her a different person. "I got really rude and mean and very heartless," she says. And she traces the change to one source: the commission. Salminen's collections agency purchased debt for pennies on the dollar from large lenders like Capital One and Bank One, cycling the names and credit histories of its new "customers" through its vast call center. Hooked up to an automated dialer, Salminen scrolled through lists of 500 debtors at a time, typically calling through the list least twice a day. She would call employers, family and neighbors to track people down. If she could get a debtor on the phone, her job was to negotiate a plan for payback. "Some would be open to talk," she says. "Many just hung up." "You'd know within the first few minutes if you were going to make money or if you were wasting your time. You just knew," Salminen remembers. "You'd mark down a hopeful call and if you couldn't get a hold of them again, you knew they were lying. But if you had constant contact, you knew they were going to pay. It may not be in a week. It may not be in a month. But you just kept on it." Salminen's employer kept a third of the debts it settled. Individual collectors received 10 percent of that amount in commission. Salminen thinks the commissions encourage debt collectors to push the limits of their job. "I remember one collector," she says. "People said she made $70,000. She told a foreign person she would call INS if he didn't pay his bill. He paid. You're not supposed to do that." The drive for a commission steered Salminen toward "easy" customers, students and seniors, and away from those who were savvier about avoiding payment. "College students, those were the easiest," Salminen remembers. "They had parents. They just had to swallow their pride and go get the money. I liked college students." People with failed businesses proved harder: "They were sneakier. You really had to hunt them down, and you weren't going to get anything out of them because they were probably going to file bankruptcy anyhow." Salminen left debt collections when a debtor threatened to sue her for harassment and her employer refused to support her. Now working in financial customer service, she says she's much happier. "I'm not working in collections and I'll never go back. It's horrible. You come home crabby. You live on the commission. It's sad. You listen to all these sad stories and you're getting angry because they just cost you another $500 on a check. And really, is that fair? This is their life you're collecting on."

THE CHECK CASHER

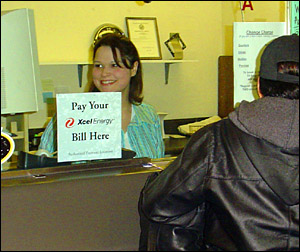

Missy Ludwig applied for a job at the Money Exchange when she learned she was pregnant. "It didn't require any heavy lifting," she remembers. Now five months along, she also appreciates the role the store plays in her life. Her fiancé works there. Customers have become poker buddies. Regulars stop by to get updates on her pregnancy. That's not to say the Money Exchange has a cozy neighborhood feel to it. "I like being involved with people, just not through a glass wall," Ludwig says of the bulletproof shield separating her and her customers. "It's not my ideal job, but for others it works out well. We have people who have been here for years." Indeed, Ludwig says her check cashing store plays a vital part in its St. Paul, MN. neighborhood, an urban stretch of auto lots and fast food restaurants. The Money Exchange is part of the booming alternative financial services industry, made up of non-bank entities that provide some sort of bank-like service. Customers shun banks for these services for a number of reasons. The hours are better. Bounced check fees and minimum balance requirements may make them distrustful of banks. Transactions create less of a paper trail. And multiple services offer one-stop convenience; a person can cash her paycheck, pay her bills, wire money to a relative and walk out the door knowing how much cash she has for the week because it's in her hand. Then, of course, there are credit problems. "A lot of my friends messed up and they can't have checking accounts now because of faults when they were teenagers. That's what I run into here," Ludwig says. "I have a girlfriend that just filed bankruptcy. She's no longer allowed at Wells Fargo [Bank] because she ran up so much debt she's a liability. So now she can't go anywhere but a check cashing store to pay a fee to get the money that she earned." Ludwig likes to distinguish her store from the more predatory alternative financial services like car title loan shops and payday advance dealers. Payday advances are high-interest loans held against future earnings and can snare low-income workers in a trap of interest and fees. Despite their risk, Ludwig says people stop in looking for payday loans, especially as money gets tight at the end of the month. But the Money Exchange is happy with its profits from check cashing alone, about $7,000 on an average weekday and up to $25,000 on a Friday. "Payday loans aren't a venture the owner wants to pursue," Ludwig says. "It involves more insurance." As a result, customers never leave the Money Exchange owing it any money. All the fees are taken out up front. Signs taped to the bulletproof glass list the store's rates: 3 percent on payroll checks, 6 percent on insurance checks, and so on. "If people complain about our rates, I say, 'Well, go get a bank account.' They say, 'I can't.' Well, you're stuck." In defense of her store's fees, Ludwig points out the trouble people can encounter at banks. "It happens. You overdraft your account and it's $33. If you do it a few times, that's a huge chunk. Here you're paying $4 up front to cash your check. It balances out pretty well." Asked why she thinks people run into credit problems, Ludwig looks to the blighted street outside. "I think people have bad credit because of the area that we're located in. It's in their upbringing. Their parents do it, and they follow in the same lane." She sees a lot of kids who dream of making music, but they ruin their credit on expensive equipment. "I have a lot of rappers that come in. They've gotten their credit off to a bad start, so they're stuck here." THE REPO MEN

Life as a repo man may have distorted Dale Hedge's view of the working world. "Yeah, I've been threatened, shot at," Hedge says of his job. "But who hasn't?" Hedge has survived 43 years in the business, chasing down debtors who have defaulted on their vehicle loans. He has earned an impressive reputation, bringing some form of closure to, by his count, 99 percent of his cases. Hedge attributes his success to his own code of conduct. While he admits his profession can attract "fly-by-night types" who seize vehicles through muscle and intimidation, Hedge says people with that approach don't last long in the business. "This is not a rip off artist job," he says. "I'm compassionate and I'm a businessman." George, a fellow repo man who asked not to be identified by last name, agrees that the job creates enemies. "They don't like us," he says. "They think we're doing something nasty, that we're the bad guys. But actually they're the bad guys cuz they don't pay the bills. We'll get their cars. It's just a matter of time." Repo men hit the streets to find the errant borrowers. "You have to make sure the vehicle is with them," George explains. "If not, you have to find out where it is. There's many ways. Your neighbor will tell. The ex-wife will tell. There's all kinds of ways." George says the job has brought him to neighborhoods of every variety. "This company has repossessed everything from cars to planes. Lamborghinis, Fords, Dodges, whatever. You name it, we've done it. We do all the way from people that can't afford nothing to people that are very wealthy. It doesn't matter. If they don't pay their bills they're no different than anyone else." With 70 years between them in repossessions, Hedge and George say they've watched Americans fall deeper into financial desperation, and the value of a contract has fallen with them. "In the old days, if a man gave you his word, he meant it," George says. "Now they swear on their mother's grave they won't do this or that and they're gone in a heartbeat." But they know debtors can fall victim to extreme circumstances as well. In truth, repo men receive very little information about the people whose cars they reclaim. They get a name, last known address, and a copy of a lien. Hedge tries to put himself in the debtor's situation when he knocks on the door. "Every one of these people had the best intentions when they were at the car lot. But everyone's situation changes: death, divorce, unemployment. Before I get to them, they've received letters, phone calls. People are afraid. They think, 'I'll take care of it tomorrow,' but it gets too late." George and Hedge see themselves as the lender's eyes and ears in the field. The debtors may have tried to explain their circumstances to the bank, but it may be up to the repo man to determine if they're telling the truth. "There was one family, we found out their boy had leukemia," George recalls. "We fought for them with the bank to make sure they could keep the car. I'm proud we did that. The bank was good about it once we said the people were telling the truth." After 43 years, Hedge still finds his job exciting. "Every day is different," he says. "The phone rings and it's a different situation. I might have the solution. It makes me feel good to be able to finalize things."

Back to Bankrupt: Maxed Out in America |

|||||

|

|||||