Part 1, 2

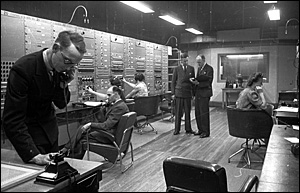

The BBC European Service control room in London, 1943, provided counter-propaganda throughout the war. Photo by Felix Man/Picture Post/Getty Images

During World War II, military scientists drew up a thick catalog of new war machines. The jet fighter, the missile, the attack helicopter, the nuclear bomb. World War II also marked the first wide-spread use of electronics in battle. For the first time, two-way radios directed tank and troop movements. Radar and sonar swept the skies and sea. And there was one simple, innocent-looking device capable of infiltrating enemy barracks, homes, and naval ships: Radio.

Radio was already a powerful mass-medium for news and entertainment. World War II marked the first time radio became a widely-used weapon of psychological warfare. Both the Allied and Axis powers transformed the wireless into an anti-personnel device. They shot disinformation and psychological shrapnel at each other. In this era (1937-45), more than a hundred propaganda stations took to the air.

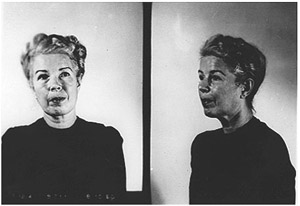

Axis Sally was one of the famous voices. She was Mildred Gillars, an American who collaborated with the Nazis in Berlin. Sally broadcast what was called white propaganda, meaning she never concealed her Nazi affiliations. Her psychological warfare was cunning. "Hello boys, American boys," she purrs, "I've got your favorite jazz recordings...remember this Glenn Miller, You'd be so nice to come home to? Who are you thinking of boys? Irene? Jane? Sylvia? Where are they tonight?" she asks, treacherously hinting their girls weren't waiting faithfully back home.

Other radio stations specialized in so-called black propaganda. That was a shadowy world of top-secret transmitters and elaborate deceptions. These stations pretended to broadcast from dissident groups on the enemy's home soil.

Axis Sally (Mildred Gillars) was the voice behind some of the most famous German radio propaganda aimed at American soldiers. Courtesy U.S. Federal Government

America's adventures into clandestine radio propaganda were directed by the the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the forerunner to the CIA. The OSS built more than a dozen stations that specialized in black propaganda.

The OSS recruited journalists and radio experts for job of fabricating lies. Betty Macintosh was newspaper reporter who had covered Pearl Harbor. "I did morale operations work…which was black propaganda. We were trying to develop a feeling in the enemy that the war was going to be lost," Macintosh remembered. She tried to make Nazi soldiers think there was no use in fighting. Like Axis Sally, her scripts also played on a soldier's most intimate fears. "We did a lot of special things like telling soldiers their wives were unfaithful and that sort of demoralizing work," she said.

Other black propaganda radio makers who signed on with the OSS included Gordon Auchincloss, a New York variety show producer, Sy Nadler, a radio scriptwriter and John Creedy, a newspaperman in North Carolina.

The idea was to create a station that sounded like a credible German radio station. "The key to black propaganda is to do as much truth as possible," Auchincloss explains, "And just bend it a little at the end, just put a little hook on it."

Sy Nadler, the scriptwriter plied the delicate art of persuasion too. "You are directing your message toward people who are a little bit receptive. Just a little bit. If they're not receptive at all, they're not going to pay any attention to it." Nadler calls it spreading "land mines" of lies in the "verbiage of truth."

Newspaper man John Creedy used the power of rumor. "There were stories that made the Nazi party people sound irresponsible compared to the German army people." Creedy built resentment by suggesting, "They had better food, they didn't risk themselves at the front. That kind of divisiveness was basic to the program." In late 1944, the German Reich lurched towards collapse. At the same time, a mysterious new radio station called out to the Germany's Rhineland. Listeners knew it as "Zwolf hundert zwolf," German for its frequency: 1212.

1212 was an American creation, code named "Radio Annie." The station's theme-song was a heart-stirring traditional tune. Compared to heavy murk of official Nazi propaganda, this voice sounded fresh and honest. "[1212] included news of what was happening on the Western front, providing very realistic and accurate news, which was something the German stations themselves were not providing," says Laurence Soley, a professor at Marquette University of author of two books on black radio.

1212 was successful, according to Soley, because its air raid reports were so grimly accurate. "Areas were being bombed by the allies. There would be photo reconnaissance. OSS. would attempt to determine what blocks had been knocked out or what houses had been knocked out, and then broadcast over their black radio stations about this destruction," says Soley. The reports added to the station's credibility and built listenership among people desperate for information.

1212 announcers were either fluent German-speaking Americans or Germans who collaborated with the Allies. Broadcasts came from a powerful transmitter in Luxembourg.

A classified report from the U.S. 12th Army shows the Americans believed their propaganda efforts were working. "There were Germans who thought radio 1212 came from bunkers because at times it was technically imperfect. Many Wermacht officers and soldiers followed the station night after night, keeping score by its front news." The report concludes, "Annie was building up her audience."

Operation Annie's team worked from trailers on the grounds of a well-guarded mansion in Luxembourg. Initially, the broadcasts avoided anti-Nazi rhetoric. 1212 was simply pro-German. Patricia Swain was stationed there. "Annie used to pretend to be a free German station run by free Germans inside Germany. It was all a lot of nonsense, but it worked," she says.

Swain recalls that to keep its cover intact, 1212 claimed to originate from different locations each night. Swain remembers the work it took to keep up the charade on the radio. "They said, 'We have to pack up, we have to go because the Allies are nearly here!' Then there would be a lot of banging and shifting of radio equipment." Announcers would promise to open up the next night from another location. "People are pretty gullible on the whole. They'd been lied to for so many years they were used to believing what they heard," Swain remembers.

In early 1945, as the Allies pressed deeper into Germany, General Dwight Eisenhower ordered the station to begin faking news. It was time for Operation Annie to cash in on her credibility. "Eisenhower wanted the station to make the Germans think that the Allies were moving more quickly than they actually were, making them retreat and take action like that thereby undermining support for Hitler," says author Laurence Soley.

Eisenhower's scheme apparently worked. Panicked Germans clogged the roads and were able to slow the retreat of the German army.

Radio Annie broadcast for 127 nights. It finally signed off by pretending that Allied troops had caught up with the rebel broadcasters. Listeners suddenly heard shouting in English and sounds of a scuffle. The German announcer cried out for someone to play a record. Then Annie's theme song rolled, and abruptly fell silent.

Continue to part 2