![]()

Part 1, 2

President Franklin D. Roosevelt, 1942.

Photo courtesy of The National Archives

During World War II, 16 million Americans served in the military and millions more mobilized on the home front. Through the 1940s, patriotic refrains inundated movies and radio shows.

"Never in the memory of man has there been a war in which the courage, the endurance and the loyalties of civilians played so vital a part," said President Franklin Delano Roosevelt in a typical wartime address to the nation.

The government had names for those who resisted: "slackers, jellyfish and worms." But more than 44,000 men registered as conscientious objectors.

In the first World War, there were basically two options for conscientious objectors: fight or go to jail. In World War II, the draft law allowed COs to opt for non-combat service in uniform. Many became medics. Or they could sign up for a new outfit called the Civilian Public Service, working on farms, clearing trails or tending patients in mental hospitals.

"It's hard to understand now how deep your commitment to pacifism would have to be to take this stance during World War II, which was almost universally regarded as a just cause," says author and historian Todd Tucker. "For you to be one of these 12,000 men to take this incredibly unpopular stance, you had to be almost painfully idealistic."

"We were willing to put ourselves on the line to protect other humans," says Jay Garner, a conscientious objector and the son of Brethren missionaries. "It was the killing that we objected to."

Garner had grown up in India and been deeply influenced by the non-violent teachings of Mahatma Gandhi. He had hoped to serve as a combat ambulance driver, but that option was blocked to men in the Civilian Public Service.

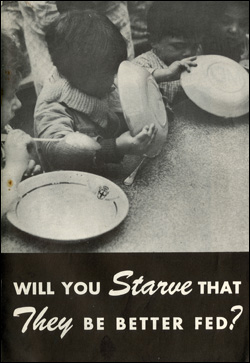

The cover of a brochure soliciting recruits for the University of Minnesota starvation study.

"Soon after being drafted, I was transferred to the Oregon coast and I was firefighting," Garner remembers. "Then I went to Augusta State Mental Hospital, taking care of a 20-bed dormitory of men. A brochure came out and said, 'Would you starve that others might be fed?'."

The brochure was soliciting recruits for medical experiments at the University of Minnesota. In the 1940s, there was scant scientific knowledge about hunger. The Minnesota experiment had two aims: to study the effects of starvation on the body and mind, and to discover the best way to feed the survivors of famine. The U.S. military hoped to learn how to feed the hungry people who would be liberated from Nazi-controlled Europe.

Jay Garner was among 36 subjects chosen from 200 conscientious objectors who signed up for the year-long starvation experiment. The subjects wanted to prove their patriotism and courage, and they wanted to be helpful.

"American boys were dying in the battlefields, suffering imprisonment, getting wounded," says Henry Scholberg, another volunteer. "And I felt it was unfair for me to be able to sleep in a comfortable bed at night and always have three meals. I felt I should be prepared to sacrifice."

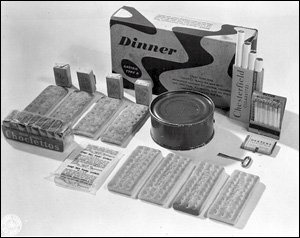

Ancel Keys developed the K ration, portable meals for soldiers in the field. Courtesy U.S. Army.

The starvation experiment was headed by physiologist Ancel Keys. In 1944 his work was already known to millions of American soldiers. Keys developed the fighting man's banquet - the K ration, the field-tested, ready-to-eat, pocket-sized portable meal.

By all accounts, Ancel Keys was a skilled and meticulous scientist.

The 36 conscientious objectors who volunteered for Keys' experiment would come to know painfully well how scientifically rigorous their new leader could be. Their ordeal also became something of a race against time. Would the war end before the exhaustive study was complete?

The first stage, called standardization, lasted 12 weeks. The men all ate the same food, about 3500 calories a day, sufficient for them to attain or maintain a normal state. They slept in a dormitory upstairs from the lab and dined in same cafeteria as the football team.

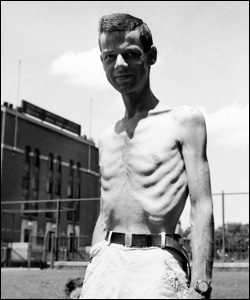

Starvation experiment participant Sam Legg. Time & Life Pictures/Getty Images

"We spent a good deal of time being tested," says Sam Legg, another participant. "The people who made the experiment were absolute geniuses at making up tests. Physical tests, psychological tests. They examined our bodies minutely. They really probed."

"It's kind of mind-boggling the number of things that were analyzed, from hearing and vision to sperm count and quality of skin," says Todd Tucker, author of The Great Starvation Experiment. Tucker says testing started during standardization and included psychological tests as well as physical ones. In addition, the men had to walk 22 miles a week and work for 15 hours.

The starvation phase lasted 24 weeks. "The meals were immediately slashed - not gradually - drastic reduction like you would see in famine," Tucker says. Calorie intake was cut in half, and the men went from three meals a day to two. Each test subject was supposed to lose 25 percent of his weight. If a man didn't lose weight fast enough, his meals were cut back more.

Their diet mimicked what Europeans under siege or occupation were likely to get: a lot of cabbage, potatoes and wheat bread. Still, the men could not get enough.

"We not only cleaned our plates, we licked them," says Jay Garner. "Talked about food, thought about it. Some people collected as many as 25 or 30 cookbooks."

Libido was an early casualty of the starvation phase. The men said that as they lost weight, they lost interest in women. The scientists were noting their subjects' flagging strength and ability to concentrate.

Hear and see the starvation experiment as one participant reviews decades-old silent film. Henry Scholberg says all 36 conscientious objectors believed the experiments would serve humankind.

Henry Scholberg remembers the time he and a date were coming home from the movies. "I said to her, if we're attacked by a bunch of ruffians, run like hell because I'm too weak to do anything to help you," he says, laughing.

"I was going to the library on the Minnesota campus," Jay Garner remembers. "They had large brass doors and I found I could not pull the doors open. I had to wait until a little cutie came along and pulled the doors open."

Public health researcher Leah Kalm interviewed the men 50 years after the experiments ended. She says the volunteers she talked to were surprised by how much starvation affected their thoughts and emotions as well as their bodies. "A lot of them talked about how they had been gregarious and outgoing individuals and how that just was gone," Kalm says.

"We became more introverted, more concerned about our own problems," says Bob Willoughby, another participant. "We were no longer concerned about the problems of the world. We weren't as concerned about helping others. Our thoughts were dominated by food."

One of the conscientious objectors stood out from his colleagues in the experiment. He stayed interested in world events and used his mind to avoid thinking about food. Participants were encouraged to take classes at the University, but Max Kampelman finished law school and began a graduate degree in political science.

"Max Kampelman was kind of an extraordinary overachiever all his life," says author Todd Tucker. Kampelman was the only Jewish participant in the experiments "His pacifism was definitively religious but ... being a Jewish pacifist in World War II was a very ideologically lonely position to be in," Tucker says.

Kampelman says he was influenced by Quakers to resist evil. "And to this day I think the power of love is an immense power," says Kampelman, who went on to serve two presidents as an arms negotiator. "And obviously it would be so much better if we could defeat evil with the power of love. Those were my thoughts at that time."

Continue to part 2