Welcome to the Real World

Jajuan Wiggins stands concentrating on a big decision: whether to rent a small two-bedroom apartment in an old building for $750 a month or make monthly house payments of $560 for a single story home in a working class neighborhood.

The tall 15-year-old squints at the piece of paper he's holding and asks the real estate agent what "fair market value" means.

"That means if you sold that house, $70,000 would be a fair price to get for it."

Jajuan decides to do it. He pulls a perforated slip from a packet and writes a check for $560.

It will be a day of big decisions for him and nine other high school sophomores at Holy Family Cristo Rey High School in Birmingham, Ala. They are participating in a simulation called "Welcome to the Real World," (WttRW) a personal finance curriculum distributed by University of Illinois Extension.

WttRW teaches 7th-12th graders about personal finance. The program lets students know what careers pay, what housing costs in their market and, most important, how every consumer decision they make affects every other. Some high schools spread the curriculum across days or weeks. Some, like Cristo Rey, pack the money-management experience into one day.

Cristo Rey administrators say their students need this information.

Many of them come from neighborhoods where good jobs are scarce and their families live paycheck to paycheck. They don't have much experience with financial planning.

"They think they already know: 'I'm gonna make a lot of money, have a big car, a big house and I'm just gonna rule the world, nothing's gonna touch me,'" says Jan Fuller, Cristo Rey's director of corporate internships. She says they have another think coming.

One day in September, the Holy Family Cristo Rey library is turned into a bustling market. Ten sophomores will spend the day there. Cristo Rey staff and volunteers are deployed at eight library tables in their roles as bankers or bill collectors.

Students' first step is to decide what job they will have. They pick an index card with their chosen career. Each job has a corresponding monthly salary drawn from national data: Food server, $1285; graphic designer, $2440; nurse, $2635.

First they deduct taxes. The amount depends on their income. Then they decide how much to save. Most of the students start with 50 percent, but they soon learn they can't pay the bills that way.

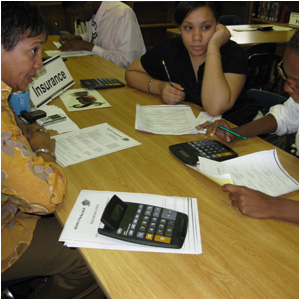

Jan Fuller sits in the middle of a long library table next to a placard that says "INSURANCE."

"What kind of car did you purchase?" she asks a husky young man named David.

"I purchased a new small truck."

"That'll be $70 a month. Write that down. Now, did you buy a home or are you renting?"

"Renting, a two-room apartment, $600 a month."

"That'll be $10 a month to insure the contents. Now, do you want life insurance?"

She tells him the cost of life insurance depends on whether he smokes. A nonsmoker, he agrees to buy some, and she tells him to write a check to the insurance company for $93. They use a calculator to figure out what he has left to spend per month, and he moves on to the next station, "Utilities."

In the course of the day students will also draw from "The Deck of Chance." These are unforeseen circumstances with price tags attached: Dog gets sick, $100 vet bill; car repair, $150; check bounced, $50. One-third of the deck is good things: birthday cash, $50; income tax refund check, $200; garage sale proceeds, $30.

The curriculum shows students the broad impact of their financial decisions.

"They're so frustrated," Fuller says. "They're running around saying, 'What do I do? What do I do? I had money, where did it go?'

"This lets you know you really have to be very careful about what you do and the decisions that you make."

Student Gabrielle Childress decides to be a food server because that's what her grandmother does. After taxes, she brings home $830 a month. She's come to the bank because she can't make ends meet.

The "banker," who is really the school's minister, Mary Ann Wilson, agrees Gabrielle's circumstances are dire. She doesn't have enough to pay for this month's food.

"What about me having a loan?" Gabrielle asks.

Wilson tells her the bank doesn't lend money just to help people make ends meet. A student loan, though, is a possibility. It dawns on Gabrielle that she should find a more lucrative career.

"Could I go back to school?" Gabrielle asks. "I need some more money. I understand that food is not gonna be the best way because I'm gonna be a skinny stick by the time I get done."

"It is possible to get a student loan for going back to college," Wilson tells her. "If you have something to show you can pay it back or if you have someone to co-sign for you, that is possible."

Gabrielle ponders the thought. She asks the banker whether being a chef or a social worker would be better.

"What do you think?" Wilson asks.

Gabrielle seems flummoxed.

"Maybe I should pick another job and start my life over," she says.

Wilson tells her that a college education led to better pay for many students she knows.

"A lot of them had to go to school, even get advanced degrees and work really hard but then they're able to get into a career where they don't have to worry about what they're going to eat through the month," she says.

The idea behind WttRW is to get students to think about their futures and make plans, rather than finding out the hard way that the job they've chosen won't pay the bills.

The program was developed for use in high schools, but it's also been adapted to help adults who aren't used to living independently: soldiers, people leaving prison, women getting off welfare.

The WttRW curriculum came out in 2003. A new edition is planned for 2010. The update takes into account some high-tech changes in the world of personal finance. People participating in the simulation will have the option of using debit cards, and they'll get socked with bank fees for online transactions.

Back to Workplace U.