An Intimate Detachment

I think of myself as approachable both on the job and in private life. Talking with strangers is one of my favorite things to do. As a 25-year journalist covering social issues, I've interviewed people many listeners never get to talk to: U.S. senators, crack addicts, political refugees, homeless children, eminent scholars, and movie stars.

I figure people talk to me because they want their stories told. When the stories are personal, the interviews lead to intimate, if temporary, relationships. When the stories are written, I move on to the next one.

But I'm having trouble leaving Russell Brockman's story behind. Since I met him five months ago, Russell has been one surprise after another. And he has made me think harder about how to negotiate an intimate relationship that is not a friendship.

The first surprise was that he talked to me. We were in a Minneapolis parking ramp. He was on a 10-minute smoke break, along with a dozen or so of his fellow students. It was my first visit to Twin Cities RISE! (TCR), an anti-poverty group that helps participants get jobs that could lead to careers.

I'd been invited to attend - but not record - empowerment class. It's the most private session, where emotions spill out and a visitor glimpses what barriers lie between the students and a good job, especially in a tough economy. Barriers like chemical dependency, not finishing high school, crippling family dysfunction, lack of any work experience.

When I'd been introduced to the students in class, I said a few words about American RadioWorks and that I'd like to get to know them all better.

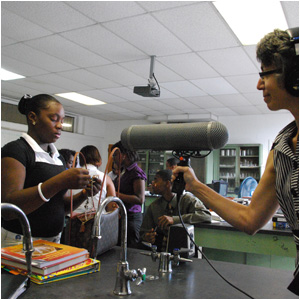

But now I'm standing in the parking lot with my enormous microphone and feeling sheepish as I ask for someone - anyone - to tell me more about themselves and how the TCR program worked. I can't remember when I've felt less welcome.

Then Russell steps out of the smokers' huddle and says, "I'll talk to you, tell you whatever you want to know." First impression: big guy, willing to defy peer pressure.

The first thing he tells me is pretty amazing. In order to "better my life," he gets on a bus at 5 a.m., comes to school, takes another bus 45 minutes to intern at a Goodwill-type warehouse, and then takes three more buses to get home at 9:40 each night. That's six hours a day on the bus.

I don't believe him at first. But then I call the number he gives me, and he never is home until 9:40, just like he says. He tells me he lives in a distant suburb so as not to be tempted by the violent crime and drugs that are part of the lifestyle he's trying to leave.

He's been in prison on and off for the last 20 years, mostly on. He has 11 felony convictions.

Russell is over 6 feet tall, a middle-aged black man with a bald head. Usually he wears jeans and a T-shirt. The intern logging the tape I brought back that first day said, "You have to use this guy" in the radio documentary. She liked his gravelly voice and booming laugh.

He's a big man with a larger-than-life personality. Unlike a lot of people I've met on the poverty beat, Russell is unapologetic about his circumstances and optimistic about his prospects.

Over the next few months I see into many corners of his life. I visit him a couple of times at TCR, watch him get comfortable with a computer, ace his classes, become the center of a group of new friends. I want to believe he's going places, but the better I know him, the more doubt creeps in.

I learn he doesn't really live up there in that suburb, but it's one of the places he stays. His roommate is a 25-year-old pregnant mother of three named Brenda. It's not romantic between her and Russell. In fact Russell fixed her up with his friend from prison, who stays there too. The townhouse is government-subsidized, so the boyfriend and Russell are both off the books. Russell is great with the children, watches them sometimes so Brenda can go out.

I interview him there one summer Friday. He's planning Brenda's birthday party.

"Got to get up at 6 to make ice," he says. They have only one ice cube tray and they need to fill coolers of pop and beer with home-made cubes. I'm incredulous. They can't afford to buy ice.

I ask what he has for income. "None," he says.

I can't fathom it. I ask about general assistance.

"I'm banned for life as far as food stamps and government assistance," he says. "All across the U.S."

He says he got caught manipulating the system. He doesn't want to elaborate.

He says he gambles a little for cash, playing dominoes and cards. He's borrowing a card table for Brenda's party.

He tells me he's planning to avenge a serious wrong done to a family member. He doesn't want to go into it.

He's a little mystified by my question about his career goals. It seems to take him a minute to remember that's the subject of my documentary.

After a long pause he says, "I just want to be comfortable. Get a decent paying job, maybe $12 or $13 an hour. I don't even have to have a home, I'd settle for a one-bedroom apartment."

He says TCR has encouraged him to have realistic expectations and to believe that he can make good choices. He says he can't stand the thought of going back to prison.

He also says he's joined a Pentecostal church, and that he owes his recent progress to Jesus Christ.

But the lines sound rehearsed, like he's telling me what he knows I want to hear. Much as I want to believe in Russell's redemption, I wonder if he can pull it off. More than that I wonder if he thinks he can pull it off - if he even wants to, really. I'm troubled by the mixed messages he's been giving, the Jekyll and Hyde persona, and I simply can't imagine how he gets by with no income.

Two weeks later, I make a routine call to TCR and learn that the police are looking for Russell.

He robbed a bank in downtown Minneapolis. The police have fingerprints on the note he gave the teller. The videotape is on the news. There's no doubt it's Russell.

At first I'm angry. How could he sabotage himself like that? What about all the people who looked to him for inspiration? My anger is personal, too. How could he betray my trust?

It occurs to me my story may be wrecked. It's supposed to be about people getting out of poverty through this program. My colleagues assure me that I've still got a good story. . What's happened with Russell helps illustrate what TCR clients are up against.

Still, I feel sad, the way I do when something awful happens to a close friend.

I go to his first court appearance just to look him in the face. I glare my outrage across the courtroom railing. He meets my gaze once and doesn't look at me again. The courtroom seems very familiar to him.

In the next few weeks he will plead guilty to bank robbery. He says he did it because he fell off the wagon and wanted money for drugs.

A few days after Russell is arrested, he has a hearing to decide where he should stay pending formal charges and then trial. His public defender, Manvir Atwal, argues that Russell should go to treatment instead of back to jail. But the prosecutor's case to keep him locked up seems cut-and-dried. Russell has 11 prior felonies. He's even been charged with - though not convicted of - bank robbery. He has no family in town, and no permanent address.

But Atval prevails. She says Russell fell off the wagon after nearly three years of sobriety. He's been trying hard to rebuild his life. It's his addiction that sabotaged his efforts.

The judge agrees to send Russell to a halfway house - though once he is sentenced he will have to serve time in a federal penitentiary. Atwal tells me she will ask the judge to depart downward from the sentencing guidelines by calling character witnesses: his mother, for example, and the FBI agent who took his confession. I wonder if she will also use the radio documentary we are about to finish.

While he waits for sentencing, Russell stays in touch from the halfway house. He lets me know about all his court appearances and I always go. He has to account for every minute away, and I'm on his authorized visitor list, so he's eager to spend as much time with me as possible.

I buy him cigarettes when he asks for them and buy us a few inexpensive lunches on the company. I'm grateful for the stories he shares, especially about life in prison. Who knew: Sex with female guards costs $50-$150; drugs are a little more expensive than on the street, but easy to get; gang affiliation is just as important on the inside as on the outside.

One day he leans over the table in a food court and says he's been talking to me all this time because he thinks I'm attractive. I tell him that's nice but I'm not interested.

I don't feel as casual as I think I appear. I'm not afraid, but I am shaken.

The next day he asks if he made me uncomfortable and I tell him yes. We don't speak of it again. But I keep turning it over in my head.

Finally I conclude the man can't help hustling. He's charming and he knows how to talk. He boasts about coming to Minnesota from Chicago, walking into all-white bars and never buying a drink.

With us, you could call it a hustle, a friendship, or a quid pro quo. He gets cigarettes; I get stories. But I'm sure he would talk to me anyway. Most journalists don't pay or give people gifts for information. The smokes are more like a favor it's easy to do for someone.

It doesn't really matter what our relationship is called. But labels mean everything when it comes to Russell's future. His prison sentence hangs on whether the court says he's a career criminal. If you have a pattern of committing felonies - a career - you're sent away for longer than if you have one or two. He's not sure whether his 11 will be rolled up into one or two, or counted separately. It could mean the difference between four years and 20.

At American RadioWorks, we don't need happy endings. We try to reflect reality. But in Workplace U we set out to tell a story about ladders out of poverty, and how people reach that first rung in order to build a career. Now "career" is the term being used to seal our hero's fate.

I feel naïve for wanting Russell to be a hero. In my head I know he's just a man with a big personality and a sad history. But I wanted things to turn out better for him, and I'm still hoping they will.

Back to Workplace U.