|

|

All by herself, Laurie Bradford embodies the ambivalence. She's a 44-year-old single mom in Casper, Wyoming with a hard-luck story. Her husband started hitting her. He went to jail for domestic violence. For a short time, Laurie and her daughter got a check, food stamps and medical coverage through Wyoming's post-reform welfare system. But it was tough to live on a check for less than $200, and Wyoming's system is quicker than most to cut single women off when they start to make some money. Bradford and her daughter spent a couple of stretches in a Casper homeless shelter. Their struggles make Bradford angry. In Wyoming, at least, welfare reform is "not a success," she says. Yet Ms. Bradford has struggled through. She now gets housing assistance through that same Wyoming system while she goes to nursing school on a student loan. When she gets her degree in a couple of years, she says, "I can do what I want, go where I want, do what I want to do." When she talks about friends from her homeless days, women who are still in and out of shelters, she says, "It's sad because they've been given opportunities ... and they just continue the lifestyle." In short, it's tough out there and government should do more, but if you don't make it over time, it's your fault.

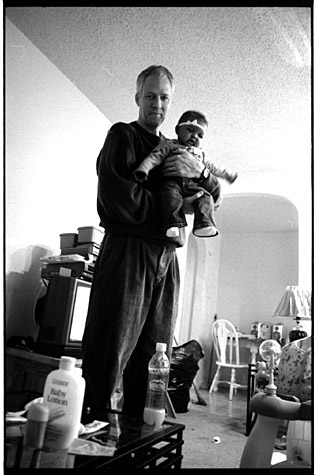

John Biewen with Lafhesa Powell's daughter, Zyshani, in Camden, New Jersey. I've seen this ambivalence again and again, in individuals and in the nation as a whole. Americans disagree endlessly about why the poor are poor and what, if anything, the rest of us should do about it. Many blame poor people themselves, stressing mistakes or bad character, while others point to what they consider an unjust society. And a lot of us can go either way, case by case. I've been exploring poverty in the United States for almost 20 years through an intermittent series of documentary projects. The angles and emphases have varied: migrant farm work; the "poverty industry"; welfare-to-work efforts in Indian country; the causes and costs of child poverty; the rising numbers of working poor; the all-too-common entanglements of poor Americans with the criminal justice system. I've interviewed dozens of poor Americans, people of varied races and ethnicities in practically every region of the country. In almost every case, within just a few minutes of conversation, you can identify the mistakes that led to a poor person's troubles: drug or alcohol abuse, teen pregnancy, criminal trouble, failure in school. I've also noticed that the people who pay the biggest price for such mistakes, who wind up as poor adults, are the ones who lacked a cushion to recover from their poor choices - that is, those who grew up poor, or in any case, who lack a family support system. Laurie Bradford's family is scattered and troubled; she has no relatives she can rely on for a loan, a guest room, even a couch. "Thank God for places like [Seton House,]" she says, referring to the Casper homeless shelter that got her and her daughter through. When asked in surveys, Americans say they want to help poor people make their lives better, but don't like giving handouts. The long-running struggle over government's response to poverty is all about these mixed feelings. How should society reach out to people who lack opportunity, but at the same time, require just the right amount of effort? See other poverty-related documentaries by John Biewen: Hard Time: Life After Prison

The landmark 1996 welfare reform law, the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act, was yet another expression of ambivalence by the American people and their representatives. Liberals, including some people in the Clinton administration, wanted a system that nudged single moms off cash assistance, but instead offered better and more meaningful help: job training, childcare subsidies, health coverage and other supports that help people survive on low-paying jobs. Many conservatives believed that welfare encouraged dependency. They wanted government to do less: move people off cash assistance and let them sink or swim. The resulting law was a vague compromise between those positions. The patchwork of state laws created after 1996 range from generous to strict, but is mostly a complex combination of the two impulses. Ten years later, the results are mixed. In the first few years after welfare reform, the nation's welfare rolls plunged more than anyone expected, from five million households to two million. The number then leveled off as the economy slowed. Studies suggest that overall, single mothers are more likely to be working and have more income than they did in 1996. Yet the percentage of Americans in poverty has changed little. A low-paying job puts more money in your pocket than a welfare check does, but still leaves you poor. Looking at the results ten years later though, I find myself struck more by the good news than the bad. Clearly some families suffered and continue to do so, but the evidence suggests that a larger number of single moms have built better lives for themselves and their children, and some have thrived. The timing was ideal: Congress and Clinton acted in the midst of a historic economic boom that offered an abundance of entry-level jobs. Millions of single moms were prepared to occupy those jobs - more prepared and less helpless than a lot of us thought. The welfare rolls plunged more than anyone expected. Which led to another surprise: States found themselves flush with welfare money. That's because the federal 1996 law froze overall spending on the welfare "block grant" to the states - a prospect that looked Scrooge-like to many at the time since it didn't plan for inflationary increases. But with the welfare rolls plummeting, states had far fewer checks to write from those unchanged pots of money. They now had extra cash for antipoverty programs. States bolstered childcare programs, gave working moms more transportation help, and found ways to provide cheap medical coverage to more low-income working people. The state systems became more like those generous welfare-to-work programs that liberals had called for. With AFDC gone, the debate over how to address poverty is quieter, more technical and less ideological. More often now, it takes place on the state and local levels. How can we extend medical coverage to more of the uninsured? How can we help more low-wage workers get high-quality, affordable childcare? The big names in Washington aren't talking about poverty, and that's bad. But they're not slinging mud over AFDC "welfare queens" either, and that's just as well. Poverty American style persists, and so does our ambivalence. It's that ambivalence, I guess, that causes the richest country in the world to tolerate so much poverty and inequality, decade after decade. It prevents us from taking bigger steps that could virtually wipe out poverty: health coverage for all, a Marshall Plan for poor cities, a higher minimum wage, a resurgent labor movement (and laws to give it more leverage), and so on. And yet taxpayers are spending more than ever on antipoverty programs, and America's poor are not as poor as they used to be. You take progress where you can find it. And I'm surprised to find myself concluding that, at age ten, the move to end welfare as we knew it looks like a modest kind of progress.

Back to After Welfare |