|

| ||||

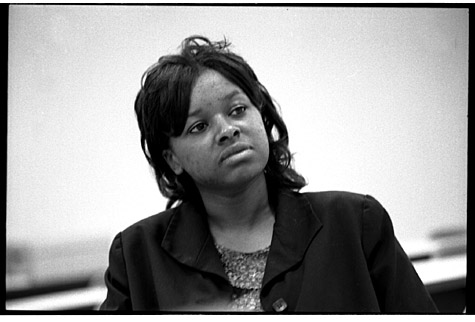

Every single mother of three has her hands full. But here's one 25-year-old mom who knows what 'overwhelmed' really means.

Aleric was born six weeks prematurely, with asthma and acid reflux. As he grew, Adriane learned he has a condition that makes his heart race. Then came learning and behavior problems. "The amiodarone is for his heart," she explains, pointing to the bottles of medicine arrayed on the counter. "The hydroxyzine and the Trileptal ... they're working on the behavior issues to kind of calm him down. The Flonase and Singulair are part of his asthma medication. He also takes two different treatments in the breathing machine." After swallowing one of his chewable pills, Aleric lets go with a hearty belch. "What do you say?" his mother prompts. Aleric thinks for a couple of seconds. "Thank you." Adriane chuckles before trying again. "What do you say when you burp, boy?" "Excuse me." "OK, then." | ||||

| ||||

|

Adriane has been on Tennessee's welfare program, Families First, off and on since 1999. But she's tried to hold down a job. She was working-full time as a nursing assistant in 2004. That's when Aleric, then 18 months old, started a new heart medication that altered his personality. "He was pretty much quiet, you know, a normal child, but then after awhile it was like he turned into a monster," Adriane recalls. "Mean, fussing, just totally out of control for a child." Adriane got help for Aleric, but his health and behavior kept on causing her stress and worry. Then Adriane's employer went out of business. She qualified for a state welfare check, but now she had to cope with a troubled kid and a frustrating job search. She saw some literature about depression and recognized the signs in herself. She contacted her welfare case worker about Family Services Counseling, a program Tennessee created for its Families First clients in 2000. Under the 1996 welfare reform law, each states gets an annual "block grant" from the federal government to run its welfare-to-work program. With the welfare rolls down since 1996, states had extra money from the block grant to spend on new initiatives. Lots of states, including Tennessee, strengthened childcare and transportation programs for their welfare-to-work clients. The counseling program is designed to help welfare moms solve personal problems that can keep them from holding down jobs. Adriane's family services counselor, Demecca Puryear, remembers the "lethargic" Adriane she met in the fall of 2005. Puryear did not press Adriane to go to work. She steered her to a psychiatrist who put her on antidepressants. Once her spirits and energy lefted, Puryear says, Adriane "took off like a rocket." Soon Adriane was back doing part-time work as a nursing assistant, and before much longer, had started a full-time job with AmeriCorps, teaching parents to read to their kids. "It was a big step for me," Adriane Dortch says, "to just come to the reality that I needed some mental counseling for myself in order to be a better parent, functioning every day." Besides counseling, Tennessee takes other steps to help poor women prepare for work. The state used a waiver from the federal welfare law to do a rare thing. It allows welfare moms with math and reading skills below the 9th-grade level to get a monthly check while catching up on their education, and the clock doesn't start ticking on welfare time limits. In most states, since the 1996 law, you have to be in job training or looking for work to get a check. In short, Tennessee has taken a gentle approach to moving single mothers off welfare and into the workforce. Some would say, too gentle. Nationally, the number of families on welfare has fallen by more than half; Tennessee has cut its rolls by just a quarter. "Tennessee has chosen a program that is, in fact, a bit of a longer path to self-sufficiency," says Ed Lake, deputy commissioner of the Tennessee Department of Human Services. "But it's because it is based on Tennesseans' circumstances. Low literacy rates, higher levels of poverty in Tennessee means that there's not a magic bullet and the framers of our statute and our program recognize that." In contrast, for example, to Western states that practically shut down their cash assistance programs after 1996, Tennessee has large communities of entrenched, concentrated poverty, in Appalachia to the east and especially in inner-city Memphis. Many single mothers in those communities were simply not ready for the workforce, says Lake. "We could push people into the Wal-Mart jobs," he says, "but ... they'll be the first to be fired or laid off when bad times come." Tennessee officials argue that it makes more sense to help single moms prepare before sending them into the labor force. "That's going to be the ticket out of poverty." As of early 2006, Tennessee still had 70,000 households getting cash assistance. To those who favor tough measures to move families off welfare, Tennessee looks like a failure. The libertarian Cato Institute, for example, gave Tennessee a "D" in a state-by-state ranking of welfare-to-work programs. But looked at in another way, Tennessee's more patient policy seems to be working. The federal welfare law gives bonuses to the five states that move the most unemployed welfare recipients into jobs, as opposed to getting them off the rolls through sanctions or time limits. Tennessee has consistently received those bonuses.

Back to After Welfare | ||||