|

| ||||

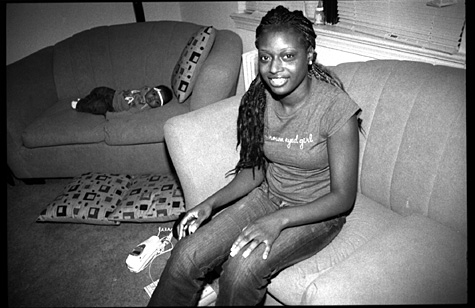

In an old brick apartment complex in one of the many poor sections of Camden, a 19-year-old mother dresses her six-month-old daughter. The baby has just woken from a nap. She squirms and coos as her mother puts her in a tiny dress. The mother, Lafhesa Powell, has striking, braided hair extensions, but her baby, Zyshani, doesn't have much hair at all. So Lafhesa puts a lace headband on the child's round head. "So she can look like a girl," Lafhesa says with a smile. Zyshani's father, Deshawn, is not here. Lafhesa says that when she and Deshawn met, they were both ninth-graders at a Camden high school. Deshawn walked Lafhesa to her classes. They dated for three years. "Then I got pregnant and I had Zy," explains Lafhesa. "And, um, [Deshawn is] incarcerated right now." Lafhesa and Zyshani live on a monthly check for $322 from her state's welfare program, Work First New Jersey. | ||||

| ||||

|

Lafhesa's story is painfully familiar to anyone who's followed the decades-long debates over poverty and single motherhood, particularly in urban America. The 1996 welfare reform law was prompted in large part by the perception that the old welfare system, AFDC, damaged the institution of marriage by giving young mothers a financial incentive to have babies while staying single. The 1996 law was aimed at removing that incentive. (The welfare law's preamble begins: "Marriage is the foundation of a successful society.") To varying degrees, the state programs created after welfare reform attempt to discourage single parenthood. Through time limits and work requirements, most states now send the message to young mothers like Lafhesa that a government check will not be a way of life. It's temporary help on the way to the workforce. That message has not reversed a long-term increase in single parenthood in America. Teen pregnancy has declined steadily, especially among African American girls, but that decline began in the late 1980s, well before welfare reform. The numbers suggest that many young women are simply waiting longer before having babies. According to the census data's latest figures, one in three children, and seven of ten African American children, are now born to unmarried mothers. The costs are high. Studies show that kids who grow up with both parents do better in school, are less likely to have mental health problems or commit crimes, and are far less likely to grow up poor. Lafhesa and her boyfriend, Deshawn, "used to talk about marriage," Lafhesa says. "It was like a dream for the future. But it never came." While marriage was a distant dream, Lafhesa and Deshawn talked about a baby in the short term. They didn't exactly try for a pregnancy but didn't use birth control, either, Lafhesa says. "We just wanted to have a baby by each other." She was confident, back then, that Deshawn would be a good father, would help to raise Zyshani. "I wouldn't say he just got me pregnant and left. Like, he just was looking for different things." During Lafhesa's pregnancy, Deshawn took up with a new girlfriend, then started selling drugs. In the summer of 2005, he got arrested and was sentenced to three years. "I didn't envision having to take care of me and my baby by myself," she says. "I always thought he was going to be there to help me and support Zy. I guess my vision was wrong." Sociologists and other poverty experts have tried for decades to understand why so many young women in poor communities, from cities like Camden to Appalachia to poor Texas barrios, make the seemingly self-defeating decision to have babies outside of marriage. Two Philadelphia-based sociologists have recently offered what many consider the most persuasive and nuanced explanation yet. Kathryn Edin of the University of Pennsylvania and Maria Kefalas of St. Joseph's spent five years immersed in the lives of single moms in Philadelphia and just across the Delaware River in Camden. They titled their book on their findings Promises I Can Keep: Why Poor Women Put Motherhood Before Marriage. Based on their study of women like Lafhesa, Edin and Kefalas want to explode what they call a misconception: that poor women of whatever race or ethnicity don't want the same things as middle-class women. "They're conservatives!" Kefalas says of the 162 poor women in the study, who were black, white and Puerto Rican in roughly equal numbers. "They think that it's natural and expected to be a mom, that having children is the best thing you can do with your life. They are very strongly opposed to abortion for the most part. These are very traditional people in the heart of the communities that everyone says has abandoned American values, that is unraveling American values." Kefalas and Edin found that getting contraception is not a problem for poor young women. Like Lafhesa, they tend to slide into pregnancy, not really planning it but not preventing it, either. Edin, the Penn sociologist, says it was never the lure of the welfare check that led poor young women to get pregnant. That's why the 1996 welfare law didn't seem to slow the phenomenon. Too often, she says, young women surrounded by poverty and hopelessness cannot see themselves achieving anything else. "If being a mother is the most meaningful and only meaningful thing you can find to do in your late adolescence and early adulthood, that's what you're going to do," Edin says. Young mothers put off getting married not because they're uninterested, Edin and Kefalas found, but because they revere marriage. In poor, chaotic neighborhoods, young fathers often fail to measure up as reliable husband material. So the women who've had children from these men hold out for an emotionally and financially stable relationship in which to raise their kids. "Marriage is as American as apple pie," Edin says. "Even people in neighborhoods like East Camden can't think about middle-class success without thinking about marriage." "People have the same values," Kefalas adds. "It's your ability to achieve them that's really different." Some states, led by Oklahoma, have launched "marriage initiatives" to promote the importance of marriage and teach relationship skills. The idea is to reduce poverty and the need for government assistance by keeping more low-income couples together. Researcher Kathryn Edin is an adviser to the Oklahoma program. She praises it as a worthy effort. In effect, she says, given the damage done by broken relationships, somebody has to try something. Edin cautions, though, that in order to help more low-income couples stay together and raise their children, you'd have to create a lot more jobs and a lot more hope in poor communities.

Back to After Welfare | ||||