part 1 2 3 4

By mid-July 1944, events seemed to be moving in the right direction for the Poles as the documentary film Battle for Warsaw explained:

The Russians having cleared the Germans from their zone of Poland looked poised to take Warsaw. On July 23rd the routed German Ninth Army streamed through Warsaw blowing up strategic installations as they went. By the last week of July only a garrison of some 2000 German soldiers remained. To the Poles of Warsaw, their liberation seemed at hand.

"You needed only to go out in one of the east/west territories of Warsaw to see the German troops in full retreat. We have also seen a lot of lorries taking the furniture and belongings of the German officials who were evacuating Warsaw. I believe two days before the uprising started, even the Gestapo left."

On July 27, the Russians reached the Vistula river, sixty-five miles south of Warsaw, and the next day pushed to within ten miles of the city. On July 29th, the Russians broadcast in Polish to Warsaw: the hour of action has arrived.

"We were exhilarated," says Zbigniew Bokiewicz, a former Polish cadet officer, "because at last we could fight the Germans openly."

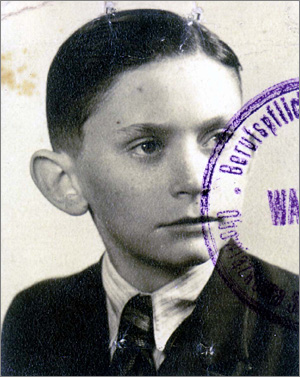

|  | | Andrzej Slawinski |

Andrzej Slawinski was a soldier of 15 in 1944. He graduated through the underground scout movement where he received artillery and sabotage training.

"Teenagers and young people," says Slawinski, "you know, definitely trying to get at the Germans for the atrocities they committed."

"At the beginning," says Marzena Szejbal, who worked as a nurse in the uprising, "[it] was very exciting. We were talking about three days, five days the uprising would be over when we shall be free."

"We heard the Russian cannons across the Vistula River," says Slawinski, "and we thought that it was a question of hours, rather than days, that they would come to Warsaw, and we wanted to establish our state and institutions before they came."

But at the same time, alarming news was reaching Warsaw that the Red Army had brutally put down a similar uprising in the city of Vilnius or Wilno, and that the Soviet secret police were executing members of the Polish underground army.

Halina Martinowa, a sargent in the Zoska Battalion remembers, "I was against taking to arms because I was perfectly sure that the Russian army, they never come to help uprising. They were waiting 'til the German would finish with the population of Warsaw."

"We thought that they couldn't do it in an important place like Warsaw, they just couldn't," says Slawinski. "We thought that our allies, Western allies would put pressure on them."

It was precisely this debate, just how much the British and the Americans would lean on Stalin, that was dividing the Polish government back in London. While the Prime Minister was frantically pressing for the rising, the Polish Commander-in-Chief, while not expressly forbidding it, sent a warning to Warsaw. "An armed rising," he wrote, "would be devoid of political sense, causing needless victims." It was an ambiguous message. The Warsaw Poles had effectively been left to decide for themselves.

"Because of all these quarrels and conflicts in London," says Jan Nowak-Jezioranski, a Polish courier, "the center of decision was shifted from London to Warsaw, and frankly, the people in Warsaw were not well informed of the international political situation. They still believed that the west will definitely resist any attempt by the Soviets to dominate Poland and other countries of Eastern Europe, and it was a completely false premise."

Go to part 4

|