The Wal-Mart Way

part 1 2 3

It's 6 a.m. at a basketball arena in Fayetteville, Arkansas, and the faithful are gathering.

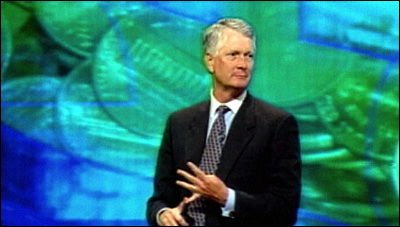

| Thomas Schoewe, CFO of Wal-Mart, speaks to employees. |

Inside, Thomas Schoewe, Wal-Mart's chief financial officer, works the crowd. He's like a cross between a high-school football coach at a pep-rally and a preacher at a religious revival.

"Your company," Schoewe calls to the crowd, "was the first company on the planet to report one quarter of a trillion dollars in sales, $256 billion! … Do you know what that is, $256 billion? That's one IBM, one Hewlett Packard, one Dell Computer, one Microsoft, and one Cisco System. And oh, by the way, after that, we got $2 billion left over."

The crowd cheers.

What began as one variety store in rural Arkansas has dethroned GM, GE, and every other major manufacturer in the country. Today, Wal-Mart is the most dominant company in the American economy.

So how did this happen?

| Gary Gereffi, professor at Duke University, who has written about Wal-Mart's aggressive use of information-technology. |

"Wal-Mart, as an efficiency machine, has just done better than any other U.S. retailer, or perhaps, any other U.S. company in history," says Gary Gereffi, a professor at Duke University. He has written extensively about how mass retailers like Wal-Mart have gained leverage to reshape the global economy.

To really understand Wal-Mart, Gereffi suggests, think of it as an information technology operation masquerading in the form of a mass retail chain.

Wal-Mart collects and tracks more detailed information about consumer demand than any other retailer in the world.

Bar codes and computerized inventories make this possible. Automated ordering makes it incredibly efficient.

| John Lehman managed six different stores for Wal-Mart over 17 years, and who now works to unionize employees. | |

"You can track sales on specific items specific weeks, specific days, specific hours of the day, when you sell merchandise the most," says John Lehman. He worked for Wal-Mart for 17 years, managing six different stores. Disillusioned, he quit to join a union trying to organize Wal-Mart employees. "You can find out what size of toothpaste is your bestseller, what times of the year you sell that toothpaste."

And each week 100 million customers stream through Wal-Mart's doors.

"Wal-Mart's leverage lies in the fact that they are at the end of the supply chain," says Edna Bonacich, professor of sociology at the University of California, Riverside. "They front with the consumer, … they know what is being sold, and they're able to use that information to tell the producers what needs to be made, when, where."

Next - part 2

|