| Moderator, Deborah Leff, is Director of the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum. |

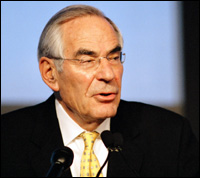

DEBORAH LEFF: Good afternoon. It gives me great pleasure to introduce to you a man who is the antithesis of "pack journalism." At the Kennedy Presidential Library, we place a special value on courage.

President Kennedy and this library celebrate courage because we believe it is integral to the preservation of democracy. Courage enables buried truths to be voiced. Presenting perspectives that aren't the prevailing point of view, that aren't the conventional wisdom, opens our minds to facts and knowledge needed to make choices that move this country in the right direction.

In 1962, as we have heard this afternoon, America wasn't all that focused on Vietnam. The Congo, frankly, was the subject of more attention in the Kennedy administration at that time. And there was a young, New York Times reporter based in the Congo, 28 years old. In 1962 he moved from the Congo to Vietnam. He reported for The New York Times there for two years and was one of a small group of reporters who questioned the prevailing point of view.

And that questioning and the brilliant reporting that accompanied it, led to the awarding of the Pulitzer Prize to our keynote speaker, David Halberstam,at the age of 30. In 1973, Mr. Halberstam published The Best and the Brightest,a book The Boston Globe has called, "the most comprehensive saga of how America became involved in Vietnam. It is also The Iliad of the American empire and The Odyssey of this nation's search for its idealistic soul."

As a mutual friend of David's and mine told me, "Mr. Halberstam combines raw energy, basic journalistic skills, hard work, and steely honesty." It is an honor to have him here to present our conference keynote, and he has agreed to answer a few questions after his remarks. So please write your questions on that index card on your chair and give them to one of our staff members.

And now, please join me in welcoming David Halberstam.

[Applause]

| David Halberstam won a Pulitzer Prize for his coverage of the Vietnam War for The New York Times. He wrote, The Best and the Brightest, the acclaimed critical history of how and why the United States went to war in Vietnam. |

DAVID HALBERSTAM: Getting an introduction like that, you should quit and just get out of town. I thought we would start with the tape. This is a true tape from the presidential library, October 2, 1963. President Kennedy meets with Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara and National Security Assistant McGeorge Bundy to discuss the war in Vietnam.

[Reading]

JFK: "What about the press out there?"

McNamara: "Terribly difficult.There are two or three good ones, but Halberstam and Sheehan are the ones that are"--

JFK: "Causing a lot of trouble."

McNamara: "Just causing a lot of trouble. They are allowing an idealistic philosophy to color all their writing."

JFK: "How old is Halberstam?"

McNamara: "About 29."

Bundy: "Class of '55."

JFK: "At Harvard?"

McNamara: "Mac was his teacher at Harvard." (By the way, that's not true.)

Bundy: "I want you to know he was a reporter even when he was in college. And I dealt with him at the Harvard Crimson for two years. So I know exactly what you're up against." Lot of laughter. "He's a very gifted boy who gets all steamed up. No doubt about it. That was ten years ago that I taught him."

JFK: "Is he one of those liberal, Harvard Crimson types?"

Bundy: "Yes, sir."

[Laughter]

Well, it's in the past now, isn't it? [Laughter] The President, President Kennedy who I greatly admire, telling Punch Sulzberger in October '63 that perhaps the publisher could find a place for me in Paris or London. And then a few years later, Lyndon Johnson telling Bob Sherrod, the great World War II war reporter, I think mostly for The Saturday Evening Post that my colleague Neil and I, Neil Sheehan and I, were traitors to the country. That's past.

Who'd have thought it? More than 40 years later, and we are still talking and arguing about Vietnam, the subject that never goes away, in part because those who should know the most have managed, in their memoirs more often than not, to tell the least.

Just last summer when the great Swift boat controversy was going on, I did an article for Vanity Fair, which noted that the debate was taking place some 30 years after Senator Kerry left Vietnam. And if in 1952, if a comparable debate had taken place between Dwight Eisenhower and Adlai Stevenson, going back the same amount of time, they would have been arguing about their service in World War I. So I'm pleased and honored to be here today, to be the keynote speaker at a conference.

And I'm sure that some of what I say will seem to be critical of the decisions of the men who were in office in that era. So I would like to say at the beginning that I admired John Kennedy as both a president and as a gifted working politician. That he was so modern and contemporary a figure, so good at making reeds on the fly, that he could see the change from politics governed by machines to the coming of television and balance those forces so well. He was so skillful. A cool, rational, fatalistic figure--

I also believe though there is no empirical proof of it-- and, in fact, the people who do try to prove it are always too selective in their dealings, in dealing with the record that he would not have sent American combat units to Vietnam in 1965. And I believe that was because he was too cool and too modern and too good a politician to waste his precious second term in the rice paddies of Vietnam.

And I believe also he would have had a better sense of the forces that were underneath the surface had we tried to challenge them. And I believe he would have probably tried to keep it on the back burner in 1964, run against Barry Goldwater, would have won big, and then would have tried to find some way out in 1965. But we do not know. There is no empirical proof.

And there are people as gifted as I who studied the record longer than I have, like Les Gelb, former head of the Council of Foreign Relations, who do not take that view.

In fact, I suspect that what I believe is at the core of my own personal problem with President Kennedy or perhaps more accurately stated, his problem with me as a young reporter -- that I was constantly taking a story of failure, of something that did not work, and moving it from the back burner to the front burner. And he wanted to keep it on the back burner.

And because I had the unique power of The New York Times at that moment and I was showing something that was on its way to becoming, if things did not turn around, a first-class foreign policy failure. No wonder that he was so furious at that small group of reporters.

A few things that probably go beyond the normal biographic note, which I think will serve us well in what I'm staying. I went to Vietnam 44 years ago. I was, as Deborah said, 28. I was, unlike what my critics said about me, an experienced reporter when I went. I had edited a very good college daily newspaper. I'd worked two summers with a metropolitan daily in Hartford.

I had spent five years in the South covering the civil rights movement, mostly in the days before it was a movement. And I would suggest, by the way, the civil rights coverage would be an excellent preparation to cover a war like Vietnam in the sense that you were covering our colonial era here at home. And then I went on to the Congo and covered the chaos there as the colonial era ended there. I joined The New York Times in November 1960, the day after John Kennedy's election.

And six months later I was in the Congo covering events there. I did well there, over more than a year. Found that I could deal with the sheer danger and terror involved in being a war correspondent and was runner up for the Pulitzer Prize that year to Walter Lippman, to Walter Lippman who never left his own house, [Laughter] which just infuriated me. I had gone all those thousands of miles away to Katanga. Walter Lippman never left his house and he won.

I got on in the Congo. And, perhaps more importantly, very well with the ambassador, Ed Gullion who was one of John Kennedy's favorites. As a young State Department officer back in what was then called Indochina, it was Ed Gullion who had helped turn the young Congressman around. And turned him from a blind acceptance of the French position to a critical assessment, which later enraged the French.

Gullion and I dealt very easily with each other because I did not have professional roots in New York or Washington, but had them in Nashville. I would not have covered America by only being in New York or Washington. So when I got to the Congo, I determined that I would move around the country, which I could do very easily. Gullion understood this.

And when I went to see him, we swapped information. To get information, you give information, particularly when you're overseas.

And we had a very, very easy, personal relationship. In fact, when I tried to do the same thing with Fritz Nolting, the ambassador to Vietnam in 1962-- I had been out in the delta and I went by to see him. I was going to tell him rather casually of my pessimistic view of what was happening. I was physically and abruptly ushered out of his office by the Ambassador himself.

I volunteered for the Vietnam assignment. Started pushing for it in early 1962 and got it that summer. In part, I suspect, because I was The Times' only volunteer. [Laughter] I arrived in July 1962.

I mention all of the above because there was later a deliberate and quite systematic attempt from the White House, Pentagon, and State Department, to diminish and destroy my reputation and that of a number of my colleagues as we became more pessimistic than the official line. And to portray us as young, naïve, and inexperienced and, in fact, as left wing wimps.

In fact, I was, I think, an experienced reporter when I arrived with the kind of experience, because of the nature of the assignment that suited me particularly well for a war that was being fought in the embers of another colonial war. I have two small places in history in the Vietnam War. The first is that I was the first "special" assigned there. For those of you who don't know what a special is, you're a full-time reporter. And it says when your byline comes in, "Special to The New York Times."

I succeeded a great reporter named Homer Bigart who had been there on TDY. So that is one thing. The second thing, when I got there I went out to a tailor on Thu Du'c and I had a bunch of strips made that said, "Halberstam, New York Times." And I put them on all my fatigues because I didn't want anyone talking to me and not knowing that he or she was talking to a reporter from my paper.

The man I replaced, Homer Bigart, great, great reporter, legendary reporter,winner of the Pulitzer Prize in World War II, winner of the Pulitzer Prize in Korea. And I was honored to replace him. Perhaps the defining story of the early Vietnam War is of Homer with his young, then young pal, Neil Sheehan, only 25 years old, going down to the 7th division area in My Tho when the first American helicopters had come in as part of the Kennedy build-up.

The old, flying CH21s looked like giant flying locusts, held together, as the wife of one of my colleagues said, "with nothing but Elmer's glue." And they went down. There were going to be three days of great victories. The senior division advisor, about to leave the country, was Colonel Frank Clay, the son of the famous Lucius Clay.

And on the first day there was a little bit of a victory. And on the second day there was a sort of typical, pillow-punching operation where the ARVN very deliberately figured out how not to have contact with the VC.

Followed by a third day with even less contact. And on the way back Neil Sheehan was gnashing his teeth and grumbling. And Homer said-- I will not repeat Homer's stutter. Homer said, "Mr. Sheehan, Mr. Sheehan, what is the problem?" And Neil grumbled and said something about, "No story." And Homer said, "But there is a story, Mr. Sheehan. It doesn't work. That's your story." And that is the defining one.

If you get there, what do you do? First off, I was disproportionately influential in the beginning for a couple of reasons. And it made me more important as a journalist. The first reason was that The Times itself, at that moment in 1962, was more important than it should have been. The television age had not yet arrived. That was the year I believe that the networks were going from 15 minutes to half-hour news shows. They didn't have resident correspondents there. They didn't have satellites. They didn't have color.

The Washington Post was not yet what it became under Ben Bradlee, a truly national paper with foreign correspondents. Nor was The Los Angeles Times, nor was The Wall Street Journal. Both Time and Newsweek had stringers and Time resolutely kept the words of warning and pessimism of its stringers out of its columns.

That meant that The Times reporter, at that moment, the collapse of The Trib was in full flight.

The Times reporter, with the 30 or 40 thousand that The Times sold in Washington, the elite 30 thousand, was really very important. You were on the breakfast table of the President and everybody else. And your words had a resonance that really went beyond what they should have had. So that was one reason that I was important.

The second is, that the policy didn't work, as Homer Bigart said. And as it doesn't work, when a policy doesn't work -- it is one thing when the policy works. The government says what is happening. It may or may not be happening, but the reporter becomes secondary. When the policy doesn't work, that's when the reporter becomes important, because the reporter then is the person who becomes the alternative source of legitimate, verifiable information.

When I got there, I thought, "How do I cover this place? This is a big country." And I decided again, using my Nashville training, to move around, get out of Saigon. Get out of the capital. And also to pick out four or five litmus test places where I would go a lot because then I could calibrate change. And also, if I kept going back, I'd begin to have some sense of connection with the advisors there. I thought there would be a growing trust, which turned out to be true.

But my main reason was to calibrate change. Now in those days, it was very hard to get on a helicopter. You put your name on a list and the people who controlled that deliberately tried to keep you away from as many battles as possible. But you could get to certain places. And you could do this, particularly My Tho, which was where most of the fighting was taking place, about 30 or 40 miles south of Saigon.

You could get there by getting in a Vietnamese taxi, great gas-guzzler. And you drove through VC territory and you paid about 300 or 400 piaster and you hoped for the best. I later began to think that perhaps the drivers themselves were all members of the VC because they were a lot more confident about getting through than I was. But you could get to My Tho that way, and you could get there any time you wanted.

And by chance, the new senior advisor of the 7th ARVN division was the man who eventually became something of a legend, the Lawrence of Vietnam, John Vann. And John Vann was a brilliant, focused, original advisor. And we became, in time, friends as I did with many, many other senior advisors. I saw General Haig earlier and his great colleague from when they were young aides to Ned Almond in Vietnam.

Fred Lad, one of the finest officers I ever met in my life, was the senior advisor to the ARVN 21st. Col. Wilbur Wilson, "Coalbin Willy" Wilson, was a senior advisor. Daniel Boone Porter, Col. Dan Porter, was the senior advisor for the entire Delta. They became friends. Bryce Denno up in I Corps --

And I would plead guilty to Secretary McNamara's description of me as an idealist. I think reporters should be idealists. I think they should be skeptical idealists but the alternative seems to me to be a cynic and I think a journalist who is a cynic is dead. I think it is very important to believe, that you believe in a kind of idealism. If you don't, if you lose faith in the truth, I think you lose faith in democracy.

But the great idealists of that era were these remarkable senior advisors in the field. They were marvelous men. I mean they all could have been school principals back home. They were educated. The United States Army was educating them. They believed in their mission. They had taken that great inaugural speech seriously. They thought of themselves as being on the cutting edge. And they found out soon-- and they were really wonderful men. I mean those were friendships in many cases that went on for a lifetime. They found out in time, these very idealistic officers who joined to serve.

They didn't do it for the paycheck. You didn't go into the United States Army or Navy or Air Force in those days because of the size of the paycheck and the knowledge that when you finished you would get a big job in industry. You did it because of a belief in your country.

They found out that Saigon was rejecting their reporting. And they became more and more frustrated because young Americans in their command were risking their lives and sometimes being killed. And as that happened, as their reporting was rejected by their superiors, they turned reluctantly to us.

And they told us the truth. And as they did I, who had just so recently been Ed Gullion's great pal in the Congo, a most favored nation, most favored journalist, (thank you for the lights) became the enemy of the people.

And the reason was that Washington has created, and it is something that we really have to deal with-- anytime we talk about Vietnam, it should hang over this conference -- Washington had created a great lying machine. And they and their truths were bouncing off it. How and why that lying machine was created is the key to what I want to say today. And it, of course, it always has its roots in domestic politics. No one likes to write about it, the roots of this thing, either in their memoirs because if they admitted, if they were the Democrats, that they had been bent by it. It would make them seem more cowardly.

Or in the case of the Republicans, it would make them seem less civil and noble and crueler to be part of a party, which had on occasion used the ugliest kind of issue in domestic debate. And what is a lying machine?

A lying machine exists on a major issue when an administration has a policy that does not, for historic reasons, work out, but where the administration believes it is important to continue it for a variety of domestic political reasons and to pretend that it works so it forces its own people at the top to be disingenuous and punishes those government employees who dare to tell the truth. And attacks the motives and professionalism of reporters who dissent.

And gradually the lines harden and the lies dominate the policy and the lying machine has a life and a dynamic of its own. It becomes as it did in Vietnam, an organic thing. So let me go back in time to try and help you understand the genesis of it. I should note here that one of the things about Vietnam is that it takes you on a journey and that journey has continued over four decades with me.

I am finishing up a book on the Korean War that Vietnam brought me to. So I have been writing and studying the fall of China and the impact of the fall of China on American domestic politics. Let us begin.

The 1948 upset of Tom Dewey by Harry Truman is a central event. The Republicans had been sure that they were going to win. It was one thing to lose to Franklin Roosevelt four times, but now they had the chance at the little haberdasher. And they were just so confident. And Dewey ran a very high-minded campaign in 1948, when Hugh Scott, who was one of the heads of the Republican Party, had urged him to use subversion as an issue, he had said, "Well, I might fleck it lightly."

And, in fact, in the Oregon primary, when he had debated the ostensibly more liberal Harold Stassen, he had said, "No. You shouldn't outlaw the Communist Party in the United States." And then he lost to Truman. And when he did, the Republicans, any hope to win on an economic issue in what was essentially a blue-collar society, were over. And so they had to find an issue and they chose subversion.

That was in the fall of '48.

And then in the next year, the fall of '49, three things happened to help them, to give them the raw meat. First, the Russians exploded Joe-1, the first Russian atomic bomb, ending our nuclear monopoly. Then, at almost the same moment, Mao took power on the mainland of China. And at the same time, the second Alger Hiss perjury trial was coming to a conclusion.

All that stuff is the fall of '49. In January 1950, the second jury in his perjury case convicted him.

And Dean Acheson, who had a very slight, very slight Hiss connection --Donald Hiss, Alger's brother had been a law partner. Dean Acheson didn't even like Alger Hiss. Knew that he was in January of 1950 going to be asked at a press conference about Alger Hiss. One of his aides, Paul Nitze said, "Let it go. Glide off it." His personal aide, Lucius Battle said, "Glide off it, Dean." His wife said, "Don't confront it." But they could tell that he was steeled and ready for battle. He had just taken such a pounding from the Republican right and the China lobby, that he seemed to want to have a confrontation. And so when he was asked a question by a reporter about Alger Hiss (by the way, by the ubiquitous Homer Bigart) he answered his famous, "I shall not turn my back on Alger Hiss," about a man he didn't even really like.

And the Republicans had their red meat and their great issue and their issue subversion and their battle cry, "20 years of treason." The Democrats, no matter how hard-line they had been, the principal architects-- it is hard to think of more hard line men than Truman and Acheson. Acheson is really about as tough a figure as you can imagine. They are on the defensive.

Consider the chronology. A month later in mid-February, Joseph McCarthy gives the first of his many speeches attacking the Truman-Acheson and George Catlett Marshall running of the country and the world. And attacks the State Department for being instruments of the Communist Party, especially on the issue of China. Then on June 25, 1950, the North Koreans crossed the border and we are engaged in the Korean War.

In late November the Chinese attacked the 8th Army up near the Ch'ongch'on, in probably an advance that went too far. And we are suddenly in a shooting war with the Chinese, the most populous nation in the world. And we are in a shooting war on the Asian mainland. It will become a grinding difficult war. Our technological superiority versus their demographic superiority, and it made an already unpopular war even less popular.

McCarthyism was deemed in the political set time to be quite successful. In the coming off-year elections, in November 1950, Republicans gained six Senate seats and 25 House seats. More importantly, because of its effect in Washington on two young Senators, was the effect of two races. One was Millard Tydings, conservative Democrat in a nearby race in Maryland, where McCarthy really personally went after him.

And the other was the Senate Majority leader Scott Lucas of Illinois who was beaten by Everett McKinley Dirksen in a race that McCarthy went out and spoke in eight times.

So let us take the moment. World War II has ended on a high note. The pressure for demobilization, instantaneous demobilization was overwhelming. And the great force that had triumphed in two theaters was gone almost overnight. Because we thought the atomic monopoly would do it. But it became a hard peace. A former ally became an aggressive adversary.

China, a much loved nation, which many ordinary Protestant Americans and some Catholic Americans wanted to turn into a Christian extension of ourselves, turned Communist as Chiang collapsed. And the British had passed the torch of leadership to a nation so recently isolationist, where much of the population was not sure it wanted to be internationalist and accept full responsibility for leading the West.

More, and this is very important, a vast part of the country, in the Midwest and on the right, had never entirely embraced the Franklin Roosevelt revolution either domestically nor, for that matter, the goals of World War II. There are a lot of people out there who thought maybe we were fighting the wrong enemy in Europe and a lot of people who thought that we should turn towards Asia, towards China.

And that, therefore, China, as Chiang began to collapse, had become an issue, which the Republicans could seize on and whack at Truman and Acheson, who were Euro-centrists. There were probably any number of reasons why the Democrats lost in 1952. They had been in power for too long. They had been in there for 20 years. You accumulate a lot of enemies.

It was surely time for them to go.

Dwight Eisenhower was a wise attractive figure, experienced, a military man who did not seem like a military man, a man who gave a comforting feeling at the height of the Cold War tensions. But in Washington, the effect of McCarthy, the sense that he had been the key was very important, disproportionate I think, in Washington. And the Democrats were on the defensive. American politics were going to get much harder edged.

No two men could have been harder lined in the Cold War than Truman and Acheson, and they were now accused of being soft on Communism. No figure had served his country better than George Catlett Marshall and he was said to have been, by William Jenner of Indiana, said to have been an agent of Communism.

The effect of that on the Democrats in the Senate, seems to me, was immeasurable.

Truman-Acheson accused of losing China. Lyndon Johnson used to like to say, "When they lost China, they lost the Congress. Well, I'm not going to be," he said, "the President who loses Vietnam, because then I will lose the Great Society."

When John Kennedy ran for the presidency in 1960, he ran as a new kind of Democrat, one more hawkish and more profoundly influenced by the Cold War than Adlai Stevenson had in 1952 and 1956.

During the campaign he had been more hawkish on Cuba than the Republicans. And I can still remember his-- I covered Lyndon Johnson that fall and summer when he made those little trips in the South. And I can remember him talking about Castro, "First I'd wash him, then I'd shave him, and then I'd spank him." It is 46 years later and he is still in power. The lines, that we as a wise society might have drawn between the kind of Communism driven in eastern Europe by the force of the Red Army, and the other kind of Communism, which was driven by colonial grievance in the third world, they got blurred.

No country was to be lost to the Communists in this new era. Not because of geopolitical consequences, although to be sure there were some. But more importantly, because of the domestic, political consequences-- lose a country and you might lose Washington. The evidence-- and this is very interesting-- there were intercepts, the National Security Agency, in the late fifties and early sixties, that the Soviets and the Chinese, it was no longer just rhetorical, they were fighting each other. But they were suppressed, these intercepts, not fed to the country as a whole. Because if you followed them, they challenged the idea of a Communist monolith. And if you challenged them, if you put them out, then you had to adjust your own policies to the idea that the Communists were not a monolith. And you had to take a certain amount of heat for the change.

One of the cruelest ironies of the Vietnam War is that every soldier who fought there wore a red and yellow patch. And that patch showed a sword piercing a wall. We were the sword and the wall was the great wall of China. Even though Vietnamese nationalism is historically fearful of the Chinese and of China. And Ho once said, I believe, of the French and Chinese, "Better to eat the French dung for a century than Chinese dung for a thousand years."

So every country would have to be defended, even if it was as in South Vietnam in George Ball's phrase, "an army instead of a country." And that led Kennedy eventually to his Vietnam commitment. As I said, he was a complicated, modern man, cool, rational, part hawk, part dove. He had as a young man given some very good speeches. I think Ted Sorensen is with us this weekend.

And Ted and Freddie Holborn, a much loved man, Fredde Holborn, were some of the architects and speech writers on it, the speech which talked about the danger of the West being, you know, engaged in colonial wars in Indochina and Algeria. He knew nationalism, not Communism, was the more powerful force in those parts of the world. But he had begun his presidency poorly.

The thin margin of victory over Richard Nixon, the debacle at the Bay of Pigs, the pounding he took from Khrushchev in Vienna-- to counter that he had upgraded the commitment to Vietnam from 600 to 15,000 to 18,000 in advisory and support roles. He was careful, however, not to send combat units. But he did deepen the commitment, escalated the rhetoric, planted the flag more deeply, brought more press coverage, and more Americans got killed. And each death, in a way, somehow seemed to become a rationale for sending more.

And he created, like it or not and aware of it or not, the great new lying machine. What had taken place back in China during the civil war, would not do. Knowledgeable China hands who predicted the fall of Chiang, a brilliant, honest general like Joe Stillwell who told the truth about the weakness of Chiang's troops, they could not be employed by the administration. All of that had worked against the Democratic administration.

So the one thing you did not want to lose a country in Asia to the Communists and you didn't want your people out there being tarred as part of it. This time everyone would be on the team, everything would be controlled. The people in the embassy would be hard liners if possible and, if at all possible, not have served any time in Asia.

Noone when things did not work out and the other side showed that it had so much more skill and dynamism, was to have a background going back to the French-Indochina war and tie what was happening in '62 and '63 with what had happened from 1946 to 1954, when the other side took hold of all the nationalism in the country and drove the French out.

On the military side, Max Taylor was the key man. And he wanted to control all the reporting from there. So he made sure that his own man, Paul Harkins, commanded the American forces. Harkins was a man whose loyalty went to Taylor directly in the narrowest sense. And he would neverstep out of line. Loyal and ambitious in the narrow sense of career, he was honest and wise and honorable in a larger sense to anything beyond his own superior, he was not.

In his mind he was there to report that the war was being won and, above all, to keep his subordinates in line and to suppress whatever evidence they came up with that the war was being lost. That made him, though it was surely not the way he thought of himself, the most political of men. A Kennedy political operative, whether he liked it or not-- just as Taylor was now a Kennedy political operative, someone who was going to report back, come hell or high water, the kind of success that they wanted.

It was a policy that corrupted those that who along with it. In his own mind, Harkins was the good soldier. He was not only fighting communism but he was staying totally loyal to his principal benefactor within the rigid, hierarchical framework of the Army. He was determined to do what Taylor, and seemingly the Army system wanted, and that was to suppress all other evidence. The orders from Taylor to Harkins, were never set down on paper but they were very real nonetheless. We were winning.

There were to be no real defeats. Victory was inevitable. The policy and the politics demanded it. The Washington rhetoric demanded it because when you invest that much more, 600 to 15,000 men, you have to have results and you have to have results quickly. So there was always going to be a light at the end of the tunnel.

In truth, you know what was at the end of the tunnel? There was a tunnel at the end of the tunnel and it was filled with VC and NVA. It was a marvel of modern engineering. Any officer, division advisor or anything else, was to know that if he did not play the game, did not get on the team, he would never get a star. You got on the team or you got out. I mention those extraordinary men that I knew, those wonderful men who were the lieutenant colonels and colonels of that era, the ones who told the truth and challenged the reporting, not a one of them got a star.

Thus was the lying machine created. And there is a danger in creating one.

It is like riding a tiger. The danger is you may end up inside. The only people you may end up fooling is yourself. The VC always, the NVA knew what they were doing. They knew they were winning. We fooled ourselves.

Let me quote Secretary McNamara, page, I believe, 37: "We, none of us, the President, Dean Rusk, myself, Mac Bundy, could get the information we wanted."

Well, that is a blood libel. It is a blood libel against any young American who served there in the CIA, the military, the idea the young Americans would not have given a chance to tell the truth could not get it right. That's shocking and it comes from the man who was the chief messenger slayer of the era who, if he saw you dissenting, would take out your career.

So, unlike the fall of China, when reporters and embassy officials and high military men like Stillwell were all friends and compared notes, the repressed became the enemy. Everybody else in the embassy was on the team. We were the outside. We were the people who had to do what Stillwell and the China hands had done back in the China days. And we did it okay.

We did it a lot better on the military side because we had great sources. Not as well on the political side because they cleaned out anybody who knew anything about the Indochina War and would connect it.

I was going to go on a little longer. I think that's really enough. But what I would say (I will take some questions.) is be very careful in this country when you start thinking that one party has a superiority in patriotism towards another. When people report things that you do not like, take and challenge the words, but not their patriotism. Try and see why there is a difference from an official line to an unofficial line and keep patriotism out of the debate because the country, if you don't, will surely be the loser. Thank you very much for having me here.

[Applause]

LEFF: You know, one thing about the perfect keynote is it gives you the appetite for so much more. And I'm about to frustrate a lot of people because we won't get to all the questions we want today but David let's try a few.

Reading The Best and the Brightest today, the delusions that led us into Vietnam seem remarkably similar to those that got us into the war in Iraq. Is history repeating itself? Was nothing learned?

HALBERSTAM: What I think for most of the senior military men who served in Vietnam and most of the reporters who went there, there was a sense of this terrible war and this miscalculation and the fact that it was finally over. One of the worse things about Vietnam -- We entered the Korean War with a bad army and came out with a good army. And we entered Vietnam with a good army and came out with a very badly damaged army.

And it really took a lot of extraordinary people to sort of patch the army back and modernize it and get rid of all the viruses that it had accumulated by Vietnam. And that was really shown by the extraordinary force that we sent into Iraq I, during the alleged Kuwait invasion, when we caught the Iraqi army in the field.

And now we have sort of in a way, done it again. I mean I think Congressman Murtha represents, I think-- When you listen to him, you are getting what the senior military have done as they over rode the Intelligence that they might have had in Vietnam about the effect of the French-Indochina War, overrode great people in the CIA, like George Allen, who is one of the most distinguished people who came out of the fifties and was not heard. Great, great figure.

So they were determined to do this and no amount of what the intelligence would reflect, the fact that there would be a tipping point, where we would go from absolute American military superiority to the point where our political vulnerabilities worked against us. The fact that we were going to be in a deficit intelligence situation, none of that mattered.

I mean, anybody who went into Vietnam, it seems to me you were hungry to know more. You went to the Algerian War to learn more. You went to the Algerian War. You saw the Battle of Algiers, the movie, (audio unclear).

You saw the Battle of Algiers. You thought, "Don't send American kids to Baghdad. We will be a target. We won't know where they are and they will know where we are at every moment. And the level of weaponry will have escalated."

So it is heartbreaking. You had me here once before to talk about that and I did. It is heartbreaking and the idea that we as a kind of Christian, capitalist society would be welcomed in that part of the world as liberators, no matter how much they hated Saddam, I just think is wrong. I think that's the more grievous intelligence miscalculation than the weapons of mass destruction, that we would be welcomed that way, that it would not work against us once we were there.

LEFF: If there had been no draft, do you think the Vietnam War would have been as unpopular?

HALBERSTAM: If there had been no draft?

LEFF: No draft.

HALBERSTAM: Well, General Westmoreland really believed he lost the war when draftees started going. I'm very aware that one of the reasons that this war does not-- I mean I think a lot of things have changed in the ensuing 40 years since Vietnam. The media could not be more different.

But one of the great differences in this society is the lack of a draft. The Vietnam War got into the bloodstream sometime in 1967. It got in through, first through upper middle class kids in college.

Some of that was, I think, absolutely, about a sense of, that this was the wrong war at the wrong time and the weaponry was disproportionate. The Vietnamese nationalism was not a threat to us. And part of it, I think is, as when President Nixon got rid of the draft, it turned out to show that it was really rather selfish on the part of-- With that it became quite quiescent, that it was about being selfish.

I think what is interesting was there is this enormous reservoir of unease in the country about the war, a sense that it doesn't work. And it hasn't really had a real manifestation. Now part of that I think is from 9/11. I think that the country is different because of that threat and because of the fact that the administration tied somewhat successfully the two together. But I think the absence of the draft, which I think is an undemocratic thing.

I think maybe a healthier country is a country where everybody's sons and daughters either have to go or have to do some kind of public service. I think that's a better country.

[Applause]

LEFF: Has any of the more recent documentary evidence changed any of your conclusions or your impressions of the key figures you wrote about in The Best and the Brightest?

HALBERSTAM: No, I don't think so. I mean I think the evidence has really been rather compelling. I think the doubts of Richard Russell, I got that. The anguish of Johnson, the fact that he was torn back and forth, that he had some grave reservations. No. I think, in effect, it's a book that's been greatly validated by what's come out in the ensuing 30 years.

And I think it has the politics right. I wish I had probably done a little bit more on the impact of the fall of China. But I think I did get that in there and the fact that we really excluded the French Indochina experience and paid dearly for it. Significantly underestimated our opponent, underestimated a force that had fought so brilliantly against the French and knew how to adapt. I think one of the great things --

The best book on combat in Vietnam is my friend Hal Moore, General Hal Moore and my colleague Joe Galloway's book, We Were Soldiers Once and Young. It is a very good portrait of the NVA trying to find out, figure out how to fight the Americans. Here they are. They fought the French. They fought the ARVN. Now here comes the most extraordinary military machine in history.

With all that firepower, how do you do it? John Vann said in that battle, they learned to fight within 30 meters. The commander of the North Vietnamese regulars who told General Moore that he told his troops, "Grab them, the Americans, by the belts," i.e., come so close that they will have to bring their firepower in on themselves.

LEFF: If the United States could have withdrawn from Vietnam several years earlier than it did, would North Vietnam have been emboldened to implement the domino theory because they would have been so exhausted from severalyears of war?

HALBERSTAM: Well, I don't know that they ever did do the domino theory. I think what worked in Vietnam was nationalism. And that the Communists had taken it over because they were the ones who had driven the French out-- They were the heirs of a revolution. And they had a military system, which brought talent to the very top. I mean, would that they could govern a country as well as they could fight a war.

I mean this geriatric group of old men that tries to run the country is-- You know, that's too bad for such a talented people. But, no. I don't think the domino theory worked. I mean Thailand was different. Cambodia had illnesses that can be discussed at other points of this conference. And we, I think, helped bring the war to Cambodia. But I think what happened in Vietnam, absolutely, they were successful becausethey all held title to Vietnam nationals.

I mean when the Chinese tried to cross, they whacked the Chinese a couple of years after the war ended. The Vietnamese, I don't think they fight very much outside their own borders. But I don't think you fight them on Vietnamese territory, historically.

LEFF: All right. And one final question. Besides idealism and the belief "promotion of democracy," what is the responsibility of the press today in the context of Iraq, and who is fulfilling that responsibility?

HALBERSTAM: Well, I think they are the bravest reporters I've ever seen in my life. I mean my colleagues like John Burns. I've never met Dexter Filkins but I think he is brilliant. Some wonderful young reporters from The Washington Post, Anthony Shahid and-- I mean I think it is so much more dangerous there. I think reporters go out. I think the networks are much less interested in foreign news and less serious than they were 40 years ago.

I think they are giant, vast corporations where the news departments are these beholden little people. And I think print has been greatly diminished. The media system is not as powerful. But I think all kinds of reporters go out every day there against great odds in a terribly dangerous venue, much, much worse, much more dangerous than Vietnam. And they are extraordinary, and their job is to try and tell you what they think is going on.

Not to be ideological, but to just give you the sense and to reflect, as I think they accurately have these days, the frustrations of the American military there, a sense that the American military did not send enough people, underestimated what would happen on the ground, underestimated the Intelligence fiasco that we see. And that this is a very, very vulnerable undertaking.

And I think they-- I don't know how they do it because I surely would not want to be a reporter there. I want to thank you very much for having me here. I'm very touched by being at the Kennedy Library, given my history.

LEFF: You know, tomorrow, we are going to continue virtually everything David talked about today. He talked about the policymakers I see in this room, Jack Valenti, Alexander Haig. They will be with us tomorrow. He talked about the reporters who were there in the war. We have in this room right now, Francis Fitzgerald, Steve Bell, Dan Rather, they'll be with us tomorrow.

He talked about the lessons learned. Wesley Clarke is here. We have Chuck Hagel, Ambassador Peterson. There is a lot more tomorrow and we thank you all for coming. Come back tomorrow.

|