|

|

| |

A

Buddhist monk lays incense at the grave of an unknown soldier at the Hue War Cemetery

in central Vietnam. Some 300,000 Vietnamese soldiers are still missing in action.

(AP Photo/Richard Vogel) |

US

OFFICIALS STILL ARE SEARCHING for the remains of roughly 1,500

American soldiers who never came home from the Vietnam war. The government of

Vietnam says it still can't find 300,000 of its own soldiers. With 25 years gone

by, the Vietnamese are turning to unconventional methods to trace the missing

in action.

Every Sunday night, people across Vietnam tune their televisions to their country's

version of Unsolved Mysteries. This program searches for the remains of North

Vietnamese soldiers who disappeared while fighting against the South Vietnamese

and the United States.

The program shows a series of photos of MIAs. They're young faces from the

1960s, frozen in black and white. The TV hosts tell where each soldier was born,

describe the date and location of the battle where the soldiers probably died,

and end the program with this appeal:

"If anybody knows where these soldiers are buried, please contact the

following address…."

Until fairly recently, viewers sent in tips and the army went out and found

remains of MIAs. But the war's been over for so long now, the clues are getting

cold. That explains why a respected professor in Hanoi, Nguyen Ngoc Hang, did

something earlier this year that he couldn't have imagined a few years ago. He

and his family hired a psychic to track down his dead brother's remains.

"My younger brother and me never believed in such kind of rubbish before,

you know," Hang says.

|

|

| |

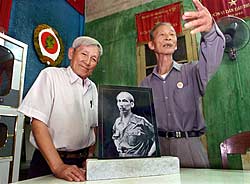

Former

Viet Cong officers Nguyen Ngoc Phi, 75, left, and Le Cong Than, 73, directed the

attack that "liberated" the city of Danang from South Vietnam in March, 1975.

25 years later, the men posed beside a photo of Vietnamese revolutionary leader

Ho Chi Minh. (AP Photo/David Longstreath) |

The professor has an amazing story. He runs a university center that trains

government officials to speak English. Hang and his younger brother both fought

with the North Vietnamese army. His brother was killed in 1970, just one year

after he went to war - the family knows that much - but the army never recovered

his body.

Hang says his family has always felt unsettled because they couldn't give his

brother a proper burial.

"So for nearly 30 years, my father visited every single cemetery. He went

to see all the graves, trying to see if my brother's name was there. We just couldn't

find him," Hang says.

Not long ago, Hang's family met a psychic who has a reputation for finding

MIAs. She sat down with the Hang's entire family in front of the altar in his

parents' house. A lot of Vietnamese have an altar in their home - it's a brightly

painted platform with a statue of Buddha and offerings for their ancestors. There's

usually a vase of flowers and fresh fruit and rice wine, and family members approach

this altar whenever they want to communicate with the spirits of their dead relatives.

So on this day, Hang's mother and father were there, his wife and son, his

dead brother's widow, and the psychic.

"And my father gave her the picture of my missing brother, and she said

that she could talk to him," Hang recealled. "So we all got together,

curious to hear what she could say."

Hang says she simply lit some incense, gazed at his dead brother's photo, and,

suddenly, started talking to the brother's spirit.

Hang adds that this wasn't some sort of freaky seance. The psychic looked like

an accountant - which is how she makes a living during the day.

Hang says his dead brother started talking through the psychic's voice. The

brother's spirit told the family that after he died, back in 1970, some villagers

buried him in an unmarked grave in a cemetery hundreds of miles away. Hang says

his brother's spirit was very precise. He gave them the cemetery's name. He told

them what town it's in.

So Hang's family piled into a van the professor borrowed from the university,

and they drove to the cemetery to find his brother. The psychic joined them. Hang

says there were more than 1,000 graves in the cemetery, but the psychic marched

straight to a row of unknown soldiers, and she pointed and said, "This is

your brother's grave."

Hang was astonished.

"Before we went, she even described the characteristic of the grave, and

we recognized it immediately," he recalled.

A Muddle

But then, Hang's family felt confused for a moment. When the psychic first

contacted his dead brother's spirit, back at their house in Hanoi, the spirit

had told them that they'd find his bones in the third unmarked grave in the row.

Yet, now that the family was actually standing in the cemetery, they were feeling

his presence at the fourth grave site in the row.

So the psychic asked his brother's spirit to explain.

"She checked with my missing brother, saying, `Hey, how come you told

us at home that it was the third grave?'," Hang says.

|

|

| |

Bui

Xuan Thanh and his family outside the gate to their house. (D. George) |

And his dead brother's spirit explained the mix-up, through the psychic's voice.

He said when he originally told the family he was buried in the third grave in

the row, he was only counting the graves of soldiers like himself. The first grave

held the remains of a village girl, so he didn't count her.

Hang says that explanation pretty much convinced his family that they were

standing at the right grave, his brother's grave. But they wanted to make absolutely

sure.

"We got to test, OK? And one of the ways of testing it is to put a chopstick

into the ground, and then get an egg, and then you put it on top of the chopstick.

The chopstick is very small. If you spend five days trying to put it on top of

the chopstick, no one would be able to do it," Hang explains.

"But if the bones in the grave are one of your relatives, you can do it.

So my father, with his trembling hand - he's 75 years old now, you know - put

the egg on top of the chop stick, and sure enough, it stayed right there."

Hang's family dug up the bones. The army helped them. Hang says, no, they did

not conduct laboratory studies to confirm that the bones were his brother's. He

says they don't need to. They're convinced they found his brother.

They brought his remains back to Hanoi and held a ceremony with family and

friends, and then, Hang says, they buried his brother in a pretty spot in a soldiers'

cemetery.

"I don't know how to describe it," Hang says. "In a sense, it

was sad news, the death of a younger brother. But this new year brings joy into

my family, and I believe that with this news, my father can live 10 or 15 years

longer. I can see a joyful light in his eyes and in my mother's eyes this new

year. We've been waiting for 30 years to find my brother."

Vietnamese officials say they're still searching for the remains of hundreds

of thousands of other soldiers, and they're funding a research project to confirm

whether psychics can really track down MIAs.

One of the study's directors says that psychics looked for 2,000 missing soldiers

last year, and found the remains in 70 percent of the cases.

|