Announcer at Woodstock: Ladies and gentlemen...Country Joe...McDonald....

Oh, come on all of you big strong men,

Uncle Sam needs your help again,

Got himself in a terrible jam,

Way down yonder in Vietnam,

Put down your books, pick up a gun,

We’re gonna have a whole lot of fun,

And it’s one, two three, what are we fightin for,

Don’t ask me, I don’t give a damn, next stop is Vietnam.

The protesters and proponents of US involvement in Vietnam have had three

decades to reflect on what they were fighting for.

McDonald: Whoopee! We’re all gonna die.

|

|

| |

National

Guardsmen stand guard on the other side of a steel mesh fence

erected May 15, 1969 by University of California officials around

a "People's Park" at Berkeley, Calif., while some of the thousands

who marched in protest pass by. The fencing precipitated a riot

in which police fired shotguns at demonstrators and one person

was wounded fatally. Governor Reagan then ordered the guardsmen

into the city. (AP Photo/files) |

For the children born during that time and after, the war, and

the war at home over Vietnam, is as distant as World War II was

for their parents.

Student: When I first got to Berkeley and walked around, I was like,

this is where it all happened, this is so cool.

Four students sit on a cement cube at the University of California

campus, a cradle of the antiwar movement. As I wait here for a veteran

of the movement, these students from the school of public health

try to imagine what the campus was like before they were born.

Student 2: The first images that come to my mind are rallies, people

standing on podiums, big posters saying "Out of Vietnam," and flashing

images of Kennedy and Nixon and young boys going away. These are things I've seen

in movies, this is what I've seen growing up. Forrest Gump, yeah, movies. I mean,

my parents.

Student 3: And I think our generation doesn't know what war is anymore.

We have no conception of what it is to have random people killed anymore.

I hear a voice behind me, turn around. It’s the guy I’ve been waiting

for. He smiles at the students.

Rossman: You are all students here? But you didn't know anything about

this place? I didn't know anything about it.

It’s so striking: deep lines carve into Michael Rossman’s face; the

students look suddenly shiny, faces smooth, eyes clear. They consider this man

with the gray pony tail.

Rossman: We divided the nation and we expressed the division in a way

that was in people's face.

Later, in an off campus coffee house, we go over some of the history. In 1964,

many students returned from Mississippi summer and the civil rights movement.

The next year, in Berkeley, Vietnam day and campus-wide teach-ins kicked off years

of protest. By 1967, frustration and rage at President Johnson’s policies

brought more radical protest. Activists tried to shut down the draft process at

the Oakland induction center. Violent conflict filled the streets, and the television

screens.

Rossman: It wasn't polite protest. Thousands of people were getting

beat and gassed in the streets. And the numbers increased and then they started

shooting the kids dead. From the perspective of those who wanted to persecute

the war successfully it fatally divided America's will. If there had not been

an opposition galvanized by the young people then there would not have been the

slowly gathering social force that kept them from going out in the madness.

Phil Ochs (Music Lyrics):

It’s always the old who lead us to the wars;

Always the young to fall.

Now look at all we won

With the saber and the gun,

But tell me is it worth it all?

The official history of the antiwar movement reads something like this: the

protests in the street helped slow the war, end the war, end the government’s

resolve to continue fighting it.

Phil Ochs (Music Lyrics):

Yes I even killed my brother

And so many others

But I ain't marching any more.

But was it really that effective?

Garfinkle: Anti-war protesters had a higher negative public-favor quotient,

according to all the polls, than the John Birch Society and the KKK. Antiwar protesters

was the most hated group in American society.

Adam Garfinkle is author of a book examining what he calls the myths of the

antiwar movement.

|

|

| |

Protest

flyer. |

Even people who were very concerned about the wisdom of the war

were not prepared to oppose it because of the company that they

would be seen to be keeping. People flying the Viet Cong flag, people

using obscenity and vulgarity. People doing things that were blatantly

anti-patriotic.

Still, by 1968, the protests appeared to be making an impact. In March, in

the wake of a strong showing by antiwar presidential candidate Eugene McCarthy

in New Hampshire, President Lyndon Johnson stunned the nation.

President Johnson: I shall not seek and I will not accept the nomination

of my party for another term as your president.

Yet if antiwar protesters took the credit for toppling LBJ – and many

say their role was inflated – they would soon be assigned blame for what

followed.

Chicago, August, 1968. It had already been perhaps the most divisive year in

America since the Civil War – in January, the North Vietnamese Tet Offensive

had shattered American illusions about a quick end to the war. Two months later,

Dr. Martin Luther King was assassinated in Memphis. Two months after that, Bobby

Kennedy was shot down after winning the California Democratic primary and then,

at summer’s end, came the Democratic convention.

Announcer at Convention: And so ladies and gentlemen, I am proud to

present to this convention the name of Hubert Humphrey as nominee for president

of the United States.

Demonstrators: Heil Humphrey! Humphrey’s a fascist pig! Dump the

hump, dump the hump!

Journalist: The truck is spraying a gas, the kids are now moving back

into the street, they’re fighting and shoving.

|

|

| |

Chicago

Police come at crowds with nightsticks and tear gas as they

try to break up protests during the the Democratic National

Convention in Chicago in August 1968. (AP Photo/Chicago Daily

News, Paul Sequeira, file)

|

The indelible image from Chicago was not Hubert Humphrey accepting

the Democratic nomination, nor the efforts to insert an antiwar

plank in the party platform. It was the picture of enraged young

people coming up against the defenders of law and order. As some

youths taunted the police, the cops waded into the crowds, clubbing

some demonstrators into unconsciousness.

Journalist: I’m trying to get far enough back so I can see what’s

happening, but it’s almost impossible to be able to give you a report as

my eyes begin to burn, cough.

A fact-finding commission called it a police riot. Yet, soon, bumper stickers

began to appear: We Support Mayor Daley and His Chicago Police. The backlash was

in full swing.

Gitlin: No doubt the precipitation of the confrontation in Chicago in

August, 1968, had very bad political consequences.

Todd Gitlin, former leader of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), and

now a sociology professor at New York University, says the backlash helped elect

Richard Nixon. Gitlin believes Hubert Humphrey, as president, would have been

under far more pressure within his party to end American involvement quickly.

Gitlin: Among those who bear the blame for that turn of events, the

’68 default, are those militants in the anti-war movement who didn’t

vote for Humphrey. I don’t exempt myself. Most people I know, including myself,

didn’t vote for president that year. That was a big mistake.

Nixon: And so tonight, to you, the great silent majority, I ask for

your support.

During his campaign, Richard Nixon indicated he had a secret plan to end the

war. A year after his election, he told America the negotiations in Paris were

moving forward. He called for unity.

Nixon: Let us understand, North Vietnam cannot defeat or humiliate the

United States. Only Americans can do that.

Nixon’s strategy was to divide domestic dissent from the great political

middle. For a time, the message played well.

Gloucester, Massachusetts, on the seacoast north of Boston. Here, like in many

American communities, the antiwar movement was made up of middle-class parents

who’d grown increasingly alarmed at their country’s behavior. In Gloucester,

they were dogged by the radical images of the national movement.

Gabin: We were constantly battling those kinds of images here.

Ellen Gabin has been an activist for 35 years – marching in Selma in 1965,

joining an American citizen’s delegation to Cuba last year, and, in the '60s,

organizing against the war.

Gabin: Locally people talked about it and said, "We told you so,

look at that. Look at those crazies." And began putting us in the same camp.

So not only were we part of the drug camp, the flower children camp, now we were

part of the bombings and the hysteria that was happening. And those things made

people afraid to be part of the movement.

Afraid, also, because people knew the government was watching. This was at

the height of an extensive US domestic spying campaign, when the FBI, the CIA,

the Army, and the National Security Agency infiltrated and kept watch over a vast

range of antiwar groups and individuals - from the Yippies and the Weathermen

to Dr. Martin Luther King to the Concerned Mothers of Calumet High School. In

Chicago alone, of the several thousand demonstrators at the convention, an estimated

five hundred of them were government agents, informants, and provocateurs.

Gabin: We were much closer to the McCarthy era than we are now. Joe

McCarthy. In a way a lot of us joked about it. But every one of us had a feeling

of terror. Even though we were doing perfectly legal things, what our constitution

said we could do. But yet there was that element of fear that they could come

for us at any time. That’s really how we lived.

But in the conservative core of the town, among the sons and daughters of

the fishermen, the call for honor and duty was answered.

Amero: I was in high school during the '60s, and we knew that our neighborhood

friends, once graduated from Gloucester High , were going to Vietnam.

Lucia Amero was born and raised in Gloucester. At Good Harbor Beach, we sit

on a dune on a cold, windy April day.

Amero: Close friends, friends you grew up with, next-door neighbors.

It just seemed as though neighborhoods were clearing out of all these young guys

that we played with, played basketball with, played kick-the-can in the middle

of granite street with.

Eleven Gloucester families lost men in Vietnam. Lucia knew ten of them. Sammy

Piscatello lived two doors down. And Frank D’amico. And her best friend,

Matty Amiro.

Amero: He went into the army, and he didn’t come back.

As 1968 came, and the protests built, Lucia watched. And stayed away.

Amero: I was never a supporter of the war. And I never objected to the

war. My stand was to support my brother, to support my cousin. We were brought

up at home doing dishes in the kitchen, singing Kate Smith, "God Bless America,"

flag waving. My mother would have never thought to keep her son home from Vietnam.

She had friends who demonstrated; friends who went to Canada. But

Lucia, who now works with veterans for the city of Gloucester, also

recalls how some people reacted to the men who did come home: men

like her brother Anthony and her cousin Ricky, who were now ridiculed

for wearing their uniforms.

|

|

| |

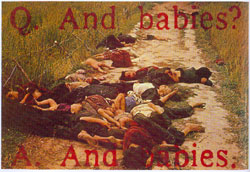

"Q: And Babies? A: And Babies." Photographer, R. L.

Haeberle; Designer, Peter Brandt. Art Workers Coalition, 1970,

offset lithograph, 25" x 38". |

Amero: And to hear people calling them baby killers and

hear that on the news; it was very, very difficult, because that

was my brother, that was Ricky. They were young guys, and they

were family, and I love them, and how could they be doing this

to them?

But if the excesses of the anti-war movement turned so many people off, so

did the response.

In May, 1970, blood spilled on a college campus in middle America.

Student: People started throwing rocks, and then they started kneeling.

We knew they were going to shoot. So we started running.

Student 2: Somebody call for an ambulance? Get another ambulance up

here!!! Two more ambulance! There’s people dying up here, get an ambulance

up here!!!

The four students shot by National Guardsmen at Kent State in Ohio was, for

many, the ultimate sign of the war at home.

Walt Russell: I don’t know why they had live ammunition.

Colonel Walt Russell and his wife Nancy had long been part of the silent majority.

But, sitting poolside on a visit with the grandkids in Phoenix, they recall their

anguish, watching the country come apart.

Nancy Russell: When those four kids got killed was out of line and inexcusable

and it really tore my heart out.

In 1965, Colonel Russell was shot in the head in Vietnam, while on a helicopter

mission. He lost part of his brain – and the use of the left side of his

body – and spent years in rehab, with Mrs. Russell and his kids at his side.

Then he won a seat in the Georgia House. As national disillusionment deepened,

and the release of the Pentagon Papers revealed official lies the government had

long been telling about Vietnam, the colonel introduced a resolution urging the

US to get out of Vietnam. Walt Russell, West Point grad, decorated veteran of

Korea and Vietnam, and a man who had little time for protesters, was fed up.

Walt Russell: My feeling was that the internal fight about Vietnam was

doing internal damage to the country. It said, "win or withdraw."

Nancy Russell kept her silence. She resented the kids who avoided service;

hated Jane Fonda for going to Hanoi. But she and Colonel Russell, raised in the

time of the Good War in Europe, came to believe that Vietnam was not the kind

of war their country should fight. Like so many other Americans, Walt and Nancy

Russell grew exhausted with war.

Nancy Russell: I was against the war from the get-go. And of course,

when Walt got shot, that didn't make me feel better. I felt my feelings and somebody's

got to get this war over pretty fast.

Fifty-eight thousand deaths were a lot. That little naked girl coming down

the road. Horrible pictures, but all that was part of it. Americans don't think

for themselves as doing that. But we did it. It's so bizarre. Not funny.

I’m Sandy Tolan for NPR news and American RadioWorks.

|