|

| |||||||||

|

Reporter's Notebook: Some thoughts about the Soviet Human Rights Movement by Robert Rand My introduction to Soviet dissidents came indirectly, through my high school Russian teacher. (I was lucky enough to be able to study Russian in high school). His name was John Moshak, and I owe him much. He was among the first Americans who traveled to the USSR on an exchange program (this was during Khrushchev's time) and he brought back tales of life under communism. He was also an amazing teacher. I was hooked on Russia for life. I began to follow developments in the USSR in the press. Names popped up. The writer Alexander Solzhenitsyn among them. In 1962, Nikita Khrushchev allowed Solzhenitsyn to publish a novella called One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich. It was the first piece of Soviet fiction to describe Stalin's Gulag. This was an unprecedented development. In his memoirs, Khrushchev says he was "proud and pleased" with the way he dealt with Ivan Denisovich. A sharp contrast to the way he had treated Boris Pasternak and Doctor Zhivago. The publication of Solzhenitsyn's novella was very much in the spirit of the secret speech. I read Ivan Denisovich and Doctor Zhivago in high school. Two literary masterpieces, each, in their own way, hovering over and under the issue of human rights in Russia. By the end of 1964, Khrushchev had been ousted. His successor, Leonid Brezhnev was in place, and a new, neo-Stalinist era of repression had begun. Dissident activity increased. And coverage of that activity in the Western press increased as well. Indeed, human rights activists in Moscow relied on contacts with Western (primarily American) reporters to keep their movement viable.

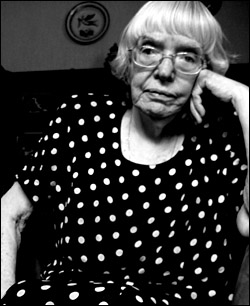

Like most human rights activists, Alekseeva's road to dissent began with Khrushchev's secret speech. Alekseeva has sharp memories of that event. "I have never seen so many people who wanted to get together after work and speak to each other in the period after the speech," she said. These gatherings were called kompaniya, and they usually took place behind kitchen tables. The kompaniya became the cornerstone of the human rights movement. "It was not only a way to spend time - to dance, to eat, to drink - but the main aim was to inform each other about various events in our past or present. We still had very strong censorship, and this was a way to share information which we couldn't get from official sources."

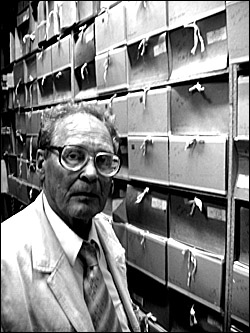

One final point: We also spoke with Sergei Kovalev, the leading human rights activist in Russia today. He was a prominent dissident during the 1960s and 1970s, and spent seven years in the Gulag and three years of internal exile. During the liberal perestroika era under the last Soviet leader, Mikhail Gorbachev, Kovalev founded a group called Memorial, which works on rehabilitating and honoring the victims of Soviet repression. After the collapse of the USSR, Kovalev served in the Russian legislature, and even acted as its human rights commissioner. He resigned due to his opposition to the war in Chechnya. I asked Kovalev whether the victims of Stalin's terror - whether those who had sat in the Gulag and had survived, be it under Stalin or in the post-Stalin era - whether those victims had ever been compensated by the Russian government. He said in the early 1990s the Russian parliament passed a law providing financial compensation, but he categorized the amount as "completely inadequate." "Let me tell you a story," Kovalev said. "I have a friend who lives in the city of Tver. He served three years in the Gulag. Less than many of us, but still, a solid period of time. At one point he spoke with the local authorities about the level of his compensation. 'Well, did you receive your money?' they asked. 'Yes,' he said, 'I got it all, but all I could do with it was buy a washing machine.' And do you know what the local authorities said? They said 'Fuck you. Get out of here!' Can you imagine? The man sits three years in prison and all he gets as compensation is a washing machine."

Back to Unmasking Stalin |