|

| |||||||||||||

|

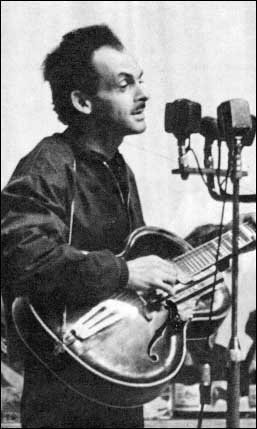

Refrains of Dissent by Hale Sargent They called it magnitizdat, or self-publication on reel-to-reel tape recorder, and it was a brand new medium for Soviet dissidents. Vladimir Kovner was there at its birth. "In 1961 was the first major recording of Okudzhava," Kovner recalls. "It was in a communal apartment in front of 20 people, all friends. We had a couple of tape recorders on a small table, with some vodka of course, and that was it."

"At the time there were only songs approved by the Union of Song Writers, and all of them glorified Soviet power," Kovner explains. "Okudzhava glorified women, love, mothers. When he sang about war, his songs were sad. He never glorified war. That point of view was incredible. And those songs accompanied by just a guitar were very attractive to us."

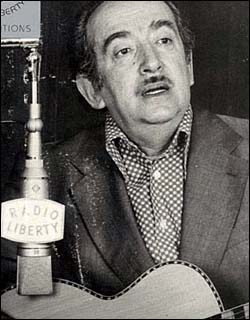

"We would just give a copy to our friends and acquaintances," recalls Vladimir Frumkin, an early disseminator of magnitizdat. "And they would make copies and give it to their friends. It was a geometrical progression because in the end, millions of copies were circling around." Many artists and collectors of the underground magnitizdat movement found their initial inspiration in Khrushchev's secret speech and in the political and artistic "thaw" that followed. When Khrushchev used his platform at the 1956 Communist Party Congress to denounce the crimes of Stalin, he brought the voice of dissent into the innermost chambers of the Soviet regime. Frumkin, who had mourned Stalin's death in 1953, describes the secret speech as the formative moment of his youth. "It was the end of the illusion," he says. "This was the point when I started getting rid of my belief in the Communist utopia." A generation of Russian artists agreed. Okudzhava, Alexander Galich, Yuli Kim, Vladimir Vysotsky-known collectively as the Russian Bards, these magnitizdat poets were unafraid to tackle overtly political themes. Their verses contained unprecedented criticisms of Stalin, the labor camps, and contemporary Soviet life. After Soviet forces marched into Prague, the Czechoslovak capital, Alexander Galich performed a song, Petersburg Romance, with the verse: [Can] you take to the square? You must take to the square. "Three days later, some men took to the square," Kovner recalls of the ensuing demonstration in Moscow's Red Square. "They were arrested and spent some time in prison."

"Of course, it was a dangerous activity because of the law against dissemination of anti-Soviet material," Frumkin says. "You could get up to three years in prison for recording and for keeping a collection of this kind of guitar poetry." But stifling the Bards' voices proved difficult. While the Kremlin controlled ownership of printing presses, reel-to-reel tape recorders were permitted in people's homes. Song collecting was widely popular, and the Bards' subversive verses could hide among less provocative songs extolling the joys of traveling or the outdoors. Magnitizdat, in fact, proved to be a more enduring medium for disseminating ideas than the printed word. "Samizdat [the underground printed press] was very limited," Kovner explains. "You can print four copies to give away, but after ten or twelve readings, it's gone. Very rarely would someone else retype it. With magnitizdat, it's different. After every concert, I could pass my copy and it would disseminate very rapidly. It was a chain reaction." Of course, the widespread popularity of the magnitizdat movement was not enough to shield its members from KGB repression. Galich was punished for fearlessly confronting the complex issues of Soviet society (In one song, he told of Gulag prisoners so brainwashed by the regime they cried with their guards when Stalin died). "The KGB thought Galich was very dangerous," Kovner says, "because he was not afraid of anything. He was not just talking about Stalin-he was talking about current events. He was not afraid to talk about Czechoslovakia. He would say anything." In 1974, Alexander Galich was forced to leave the Soviet Union for his magnitizdat recordings. He died in Paris in 1977, electrocuted while plugging in a new stereo system. Galich's friends and family wondered whether the KGB had something to do with the singer's death. Perhaps no magnitizdat performer reached greater prominence than Vladimir Vysotsky. A popular singer and actor, Vysotsky achieved remarkable fame despite never being officially recognized by Soviet authorities. In one recording, Vysotsky sang of his silver-string guitar as a metaphor for freedom: They've stifled my soul. They broke my will, and now they've cut my silver string. The song in a way foreshadowed Vysotsky's fate. He died in Moscow in 1980, still a young man. His heart, friends said, had burned out, his silver strings muted by a hard life and difficult times. More than one million people attended Vysotsky's funeral, even as their city's Olympic celebrations went on around them. Vladimir Frumkin and Vladimir Kovner each fled their homeland in darker days. They have watched the ideals that characterized magnitizdat outlive the Soviet Union, and they look back in admiration at the passion that flowed on those tapes, reel-to-reel and house-to-house.

Back to Unmasking Stalin |