|

| |||||

|

A Betrayal of the Promise

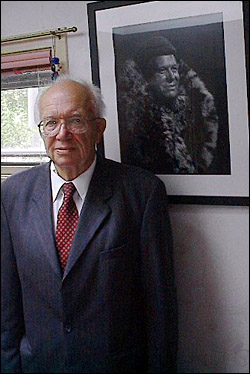

"Nikita Khrushchev said that we are trying to build paradise on the earth named communism," says Sergei Khrushchev. "But we cannot live in the paradise surrounded with barbed wire as it happened during Stalin's time." Sergei readily acknowledges that his father was complicit in Stalin's crimes. Nikita Khrushchev signed off on the death of thousands. Sergei remembers what his father wrote in his memoirs. "All of us were involved in this. And we have to tell the truth about everything." Nikita Khrushchev's involvement in Stalin's terror weighed heavily on the former Soviet leader, and, according to Sergei Khrushchev, made the secret speech an intensely personal event for his dad. "My father could not behave differently," says Sergei Khrushchev. "He could not forgive Stalin with all his cruelty for killing those people. It was more come from his soul than his just calculation and politician." After our interview, Sergei Khrushchev showed me around his house. The first stop was his butterfly collection. He told me that he used to collect butterflies in Russia, but he stopped doing so in the U.S. "I don't like to kill them anymore," he said. "Americans don't like to kill animals without any purpose. Even children," he said, "don't throw stones at rabbits." For Sergei Khrushchev, America is a much gentler country than Russia. At least a much gentler country than the Russia of Nikita Khrushchev and of Joseph Stalin. If there was a cultural icon to emerge from the Khrushchev era and the fallout from his secret speech, it was Doctor Zhivago, Boris Pasternak's Nobel Prize winning tale of romance and the Russian revolution. The story behind the novel itself was dramatic. Nikita Khrushchev banned its publication in the USSR. Kremlin censors considered it to be anti-Soviet. So Pasternak had it published abroad, under his own name, an unprecedented, and under Soviet law, illegal move. "So it was a very brave action indeed," says Peter Reddaway, professor emeritus of political science at the George Washington University. "And he was then subject to very unpleasant hounding and harassment. He wasn't imprisoned because he was too big a name. And Khrushchev wasn't going to do that when he had already launched de-Stalinization in the secret speech." Pasternak was able to write his verse, despite the hounding, until his death in 1960. It was that death, and Pasternak's funeral, which marked something of a turning point in the development of human rights in the Soviet Union. "In response to Khrushchev's secret speech," says Reddaway, "people started in a cautious way, but some of them more boldly, exercising freedom of association, gathering in squares in Moscow to have poetry readings which were not overtly political, so the authorities could not do much about it. And then this very important first large scale demonstration you could say, at Pasternak's funeral." Hundreds and hundreds of people showed up at Pasternak's funeral, against the authorities wishes, and despite the fact that the Kremlin had not officially publicized Pasternak's death. "His coffin was in a large room, and people filed by," says Viktoria Schweitzer, a young literary scholar in 1960 who attended Pasternak's funeral. "Music was playing the entire time on a beautiful grand piano. There were so many people. And lots of KGB agents. And they shamelessly took pictures of the people there. But nobody cared. The coffin was lowered. And then people refused to leave. This was the main thing. People refused to leave. They read the poetry of Pasternak. It was amazing. Every one there made a statement that he was a human being, that he was not afraid to be there." The Kremlin's persecution of Boris Pasternak regarding the publication of Doctor Zhivago did as much as anything to tarnish Nikita Khrushchev's reputation in the west, and among thoughtful Russians, who had hoped that the secret speech would broaden freedom of expression. Even Nikita Khrushchev came to realize that he had overplayed his hand. Prior to Pasternak's death, he ordered a halt to the harassment against the writer. In retirement, Khrushchev secretly recorded his memoirs in an audio diary. In that diary, Khrushchev expressed remorse at the way he had treated the Nobel laureate.

Continue to part 3 |