|

| ||

|

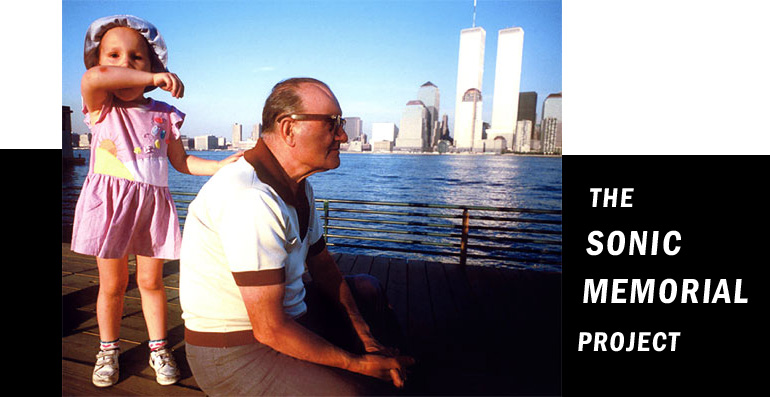

Download the full story. Visit The Sonic Memorial Project. Ray Suarez: American Public Media presents "The Sonic Memorial Project." I'm Ray Suarez for American RadioWorks. To mark the fifth anniversary of the September 11 attacks, we bring you a special re-broadcast of a Peabody-award winning documentary that chronicles the sounds and voices of the World Trade Center and its surrounding neighborhood. The program was produced for NPR on the first anniversary by The Kitchen Sisters and a nationwide collaboration. We offer it to you again; a sonic memorial that's just as moving and relevant five years later. [phone rings] Paul Auster: "From Lost and Found Sound, The Sonic Memorial Project. I'm Paul Auster." [beep] Jay Allison [outgoing Sonic Memorial phone line message]: Thanks for calling the Lost & Found Sound line here at NPR. This is Jay Allison. At this moment, we are gathering audio that relates in someway to the events of September 11, before, during and after. We're looking for audio artifacts, both personal and historic. Auster: We came together over the last year - radio producers, artists, construction workers, bond traders, secretaries, archivists, ironworkers, policemen, widows, firefighters, public radio stations and listeners - to chronicle and commemorate the life and history of the World Trade Center and its neighborhood. Allison: We appreciate your help in documenting this time, these places, and these people. Thanks. Sonic Memorial Voice Mail Operator: Message 33 was received at 10:50 A.M. Thursday. Jake Nichols: [message] My name is Jake Nichols. As a kid, I grew up in a tenement on 49th Street, Hell's Kitchen, in New York. And when the World Trade Center buildings were going up, my dad told me, "When those are finished and the race between the two buildings is over, we're going to go up on the top." My dad said at the time, "These buildings will last for 1,000 years. They'll be here forever." Auster: Hundreds of you left your testimony and remembrances, phone messages, music and small shards of sound. From these calls and from dozens of interviews done by producers across the nation comes this collection of voices, stories and sound. We call it a Sonic Memorial. Guy Tozzoli: Reader's Digest called the World Trade Center, when we announced it, "The largest building project since the Egyptian Pyramids." I'm Guy Tozzoli. I'm president of the World Trade Centers Association. Initially, I was the director of The Word Trade Center of New York, responsible for planning, designing and operating and constructing the World Trade Center. We started construction in 1967. The 16 acres of the World Trade Center sight was nothing but an old Washington Market. It was over 100 years old. One day, we found the homemade time capsule. There was this rusty thing that looked like a torpedo that had in it two packs of cigars, it had 17 cards in it from a place called the Irish Foundry Works, and the Barrister wrote this note. He said, "We are about to create this capsule. So all we could say was we are putting our cards in here and we hope that whoever digs this up will be building a greater marketplace than exists." History repeats itself. The trade center was a marketplace. Okay! There have been marketplaces for 2,000 years. And if all we do is modernize the marketplaces, we enable technology to do things better. [Music For Bowed Piano, Stephen Scott and The Bowed Piano Ensemble] Auster: Stephen Scott and the Bowed Piano Ensemble recorded live at the Winter Garden in the World Financial Center on October 25, 2000. Nearly all the recordings and audio artifacts you will hear this hour were recorded over the last 70 years at the World Trade Center and surrounding neighborhoods. Robert Snyder: The past and the present are entangled in the streets and the neighborhoods of the city. And nowhere is that more powerful than the neighborhood around the World Trade Center. I'm Robert Snyder. I'm a professor at Rutgers University in Newark. I am a historian who has written and studied New York City over the years. You've got twisty, squirrelly network of streets that goes back to Dutch New York. And that's why the streets don't conform to the grid pattern above 14th Street. They follow old Dutch farmsteads and canals. So you've got this 17th Century street layout and 20th century skyscrapers right next to each other. And you've got an 18th century church like St. Paul's, the African-American burial ground and what we think of now as the World Trade Center neighborhood was a largely maritime neighborhood, wharves going down the west side practically to the battery. You could always look around and have a sense of the past by just looking out to the Hudson River and the harbor where so much of this city's history began, where so many people got their first look at America. [phone rings; beep] Voice Mail Operator: Message 15 was received at 12:40 PM, December 2. Captain Anderson: Good day. My name is Captain Anderson. I know New York City intimately but mostly from the water. When I first started work in New York, they had just completed the World Trade Center. I have carried passengers around the tip of Manhattan hundreds upon hundreds upon hundreds of times. Gliding through the water on a sailing vessel, the entire crew and passengers lay on the deck as we sail around and we watch the spectacular buildings begin to twinkle with light. There is nothing like it anywhere on the Earth and I never became bored of it. Auster: Just south of where the World Trade Center stood, was a neighborhood of Syrians, Greeks and Turks. All that started to change with the decline of the harbor and the decline of manufacturing in the city. When the World Trade Center came in, it was partly an attempt to invigorate a neighborhood that seemed to some people to be sort of declining. And the Trade Center overshadowed and sometimes obliterated the kind of neighborhood that had been there before. [phone rings] Voice Mail Operator: Message 2 was received at 1:20 PM, April 10. Fred Apt: My name is Fred Apt. In 1931, I was 14 years old. My uncle brought me a crystal set from Cortlandt Street, Radio Row. After the war in 1946, I began selling radio and electronic parts under the name of Durf Radio. I was located a few blocks north of the Radio Row on Hudson Street. I moved my business to Westchester County when they were going to build the Trade Center. Thank you for your time. Radio Row Newsreel Recording: Although you could buy almost anything here in lower Manhattan, the great number of electronic shops in the neighborhood gave it the name Radio Row. [Archival newsreel recording: sounds of Cortlandt Street] Auster: Radio Row, 1929. The sound you're hearing comes from an early newsreel shot on Cortlandt Street in lower Manhattan, the very spot where the World Trade Center came to be. Announcer: [Archival news recording] To the Port Authority, the construction of the World Trade Center might have meant growth, but to many of the 300 small-business men in the 13 blocks to be cleared for the center and its 16 acre plaza, it meant disaster. The little-business men on Cortlandt Street and the big-business men who own the Empire State Building have fought for two years in and out of court, but apparently to little avail. And although the court battle is still being fought, the construction of the $350 million World Trade Center may have take another significant step. This is John Dunn, Channel Two News, in lower Manhattan." Apt: My father started the first radio store on Cortlandt Street in 1921. So when they started to build the World Trade Center, I said to my father, who was retired by that time, I said, "Pop, let's take a ride down to Cortlandt Street." I said this is going to be your last chance to see the area before it's completely gone. So, he said, "All right." And he put on a Macanore and his normal Fedora and we went down to Cortlandt Street. And he got out of the car and I did. He didn't say anything at first. And then sort of took a gaze down the whole length of the street and then said, "Wow. It is totally gone." That was about the extent of the conversation. I thought that it would affect him. You know reminiscing about - I started Radio Row and now Radio Row is a thing of the past. No, it didn't interest him. Hell, he acted like a New Yorker. He took it in stride. Everything changes, neighborhoods come and go. So, went back to the car and off we went. [Live musical recording: As Time Goes By played by Ernie Scott] Voice Mail Operator: Message 36 was received at 5:10 PM, November 30. Ernie Scott: My name is Ernie Scott. I'm a piano player. And I performed at the Windows on the World from 1996 to spring of 1998. During that time, CNN came and filmed while I was playing, and it was a pan around the bar and the windows. It was just a good shot. I lost a lot of friends at The Center, and I just wish that people can remember those precious moments that they used to come up to the Windows. Voice Mail Operator: Received at 3:20 PM, October 22. Robert Olin: Hi. My name is Robert Olin. I work for Thatcher, Proffitt and Wood, which was formerly housed on floors 38 through 40 of Two World Trade Center. About two weeks or so before the attack, I happened to videotape, maybe a minute or two of footage, in our office, touring a little bit of the space. I am commentating about what I see, who's in what office and things like that. [Home video recording] It's a lovely office that I spend my days and nights in. These are my neighbors, Rev and Tom. This is where we also throw footballs down the hall. [Home musical recording: "Swing me up a little bit higher" sung by Valerie Robertson] Voice Mail Operator: Message 4 was received at 6:00 PM, February 8. Lydia Robertson: Hello. My name is Lydia Robertson. My mother died on September 11 on the 97 floor of Tower One. She was the senior vice president of Marsh & McLennan for Technology, and she left quite a legacy. She had upwards of 40 foster children in her lifetime. She worked her way up from a single mom, unemployed, no education to getting herself a college degree and putting a great many of us through school and was a pretty amazing person. [Guitar instrumental, by Firefighter, Christopher Pickford] My mother, Valerie Joan Hannah was a daughter of a Texas cattle rancher/Army man and a Philadelphia socialite. She married rather young and when I was five years old, she left my father she brought along the seven foster boys that she collected and moved out and started fresh with a high school diploma and a lot of will. She started out as a keypunch operator and moved from place to place always moving up. She had glass ceiling to glass ceiling. Always collecting more foster children. She also worked as a waitress here and there. We went a couple semesters at a private school. They let her do janitorial work at night, which we didn't know about. She put a lot of us through a lot of different schools working that hard. She was big into voting rights, you know, and she didn't care who you were, as long as you voted. I was a little girl in the bank of the van once, I must have been maybe six, and she was picking up elderly to drive them to the polls. And this old man was saying, "Why are you doing this. I know you're a democrat." And my mom said, "I don't care how you vote, as long as you vote." She was someone who couldn't stand not helping if she could. She worked her way up to the top and she was the Senior Vice President of Technology at Marsh. In Tower One on the 97 floor when she disappeared. Voice Mail Operator: Message 29 was received at 7:30 am, Friday. Eric Milano: Hello. My name is Eric Milano. I'm calling on behalf of my friend who was killed in the World Trade Center. He was a firefighter. His name was Christopher Pickford. His younger brother and I collaborated to mix a compilation tribute CD in Chris' memory, which contains much of Chris' music that he created, and also contains some answering machine messages from him. [Guitar instrumental, Firefighter, Christopher Pickford] Christopher Pickford: [recorded on Eric Milano's answering machine] Spam, I've got good news. I'm starting the investigation process for a firefighter candidate. So I might be a fireman some time in the near future. [beep] Pickford: [recorded on Eric Milano's answering machine] Spam, tonight we're going to the studio. I just got this brilliant idea. Me, you and Barney, we're going to put in $33 each, we're going to get two hours in the studio. And anything more than that we'll tell people we owe them but we'll never pay them. We'll go and we'll lay down new vocals for you, and maybe we will get you ripped up into a frenzy and we'll finish it. That's what I think we should do. Give me a call. I just called your job. I told them I was Mr. Skalatey. Mr. Skalatey. That's my new name, by the way. I will talk to you, what do you think? I'm going to call Barney. I know it's probably not going to happen, but you know, shut up. Alright, bye. [Archival field recording, Tower Hollers, Hillary North] Nadine Robinson: Nadine Robinson, I'm a conceptual artist. And I recently completed a piece called Tower Hollers. It's a sound installation that was first realized at the World Trade Center residency program, sponsored by the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council in 1999. Tower Hollers is about the World Trade Center, it's 455 small boxes with speakers in it, which is the number of tenants in the World Trade Center at the time of my residency in which I played sort of a mix of work songs, hollers and labor songs that came from the South and remixed it with elevator music. I was inspired by a trip that I took on the elevators there in Tower One, going to my studios. Hearing the elevator music it was sort of "Here Comes the Sun" this like mellow tune and I'm standing there in the back of the elevator with this maintenance worker woman who was in her uniform and carrying sort of cleaning cart with all the business executives in their suits, I felt an affinity for her. And I wanted to sort of create this Musak. This music to soothe the weary worker, the secretary or even the CEO. Sort of a celebration of work and labor and the towers and what it meant. I wanted to use the speaker as a stand-in for the human voice. Custom-made speaker boxes that were huge structures called houses of joy and have a lot of meanings within the community where I grew up in the Bronx, especially in Jamaican street parties. And it'd be so important to the working class people in the boroughs and just getting through the day-to-day. [live recording, Jamaican street fair] [Ben Lion, Trinidad Recording] [New York Latin Radio station ID: Latin Mas Musica] Voice Mail Operator: Message 13 was received at 6:10 pm, November 29. Male Caller:In my many years of being in the United States, I often went to the Twin Towers to visit friends of mine who worked there. And at nighttime when everybody was gone, you could hear the Mexican radios or the tapes, listening as they worked to clean the place. Mexican, Central American. These are the guys that cleaned the place, guys that do the cooking, the guys who picked up the garbage in that place. Maybe in one of your little remembrances there, you could put in a little bit of that music, Tex-Mex, mostly Nortenos from Texas. And they're the Mexicans that came here and pick up your dirty work. They died with you guys. Help them out. Remember them. Thank you. [Conjunto by Los Tigres del Norte] Suarez: You're listening to The Sonic Memorial project. I'm Ray Suarez. Our program continues in just a moment from American Public Media. [Music for Bowed Piano] Segment B: Suarez: I'm Ray Suarez. The Sonic Memorial special continues. A fifth-anniversary re-broadcast from American Public Media. Voice Mail Operator: Message two was received at 3:10 pm, December 4. James Burton: Hello, my name is James Burton. My wife and I were married at the top of the World Observation Deck on February 14, 1998. They were looking for 55 couples who wanted to get married at the World Trade Center. Fifty-five couples, 110 people to match with 110 stories of the building. John Johnson: [singing] If there was, in the background, such a thing as a wish come true. Vanessa Johnson: I am Mrs. Vanessa Johnson. John Johnson: [singing] I would wish. Vanessa Johnson: He's always singing around the house. That's like our song. I used to come to the World Trade Center every morning on my way to work and I would take the path train to World Trade and when you come up the escalators, those long escalators in the World Trade Center, there was an electronic billboard and it said "Get Married on Top of the World for Valentine's Day." I wrote an essay, emailed it over. By 2 o'clock, I got a response saying you know, "Congratulations." I was so happy and it wasn't until later on in the day that I realized I had to tell John that we were going to get married in six days. [Home recording: The Wedding March] Whenever we'd have an argument, he's the one that came up with you know, when we see the World Trade Center we have to kiss no matter what. And at first it was like, "Uh, man, I'm upset I don't want to give you a kiss." Sometimes we would be somewhere out in New Jersey and you'd look up on the turnpike or something and there's the World Trade Center. We're sitting in the car not speaking, ignoring each other, but because we see them, now I have to give him a kiss, and you know, we kind of laugh and it was something that would put us back on track when we couldn't get on track, you know, on our own." Frederick Berman: [home recording] I want to welcome you to the World Trade Center, I'm Judge Frederick Berman, and it's my pleasure to be able to - I'm Judge Frederick Berman. For many years I've had the pleasure and privilege of performing weddings on Valentine's Day atop the World Trade Center. We did three an hour, every 20 minutes. They would put ads in papers around the country and abroad saying, "If you are interested in getting married atop the World Trade Center on Valentine's Day, write us a letter and tell us why you would like to do it." The weddings that I actually performed, I have copies of those letters so that I could personalize each of the ceremonies. The top cards are my notes. They met at the World Trade Center two years ago, he works in the food and beverage department. Eric K. Mejia: My name is Eric K. Mejia and I work in the food and beverage department. And I wrote that, I just couldn't see myself getting married nowhere else but up here. Mejia's Fiance: I was workin' downstairs as a tour guide, he was workin' up here. So it was like, everything happened here. We got engaged last year by Valentine's. He called me over to the window to see the view and he just popped the question and everybody from the food and beverage came with wine glasses and just started celebrating. [Archival announcement in WTC elevator] People in front start moving towards the closed doors. ... Welcome to the Observation Deck of the World Trade Center. [phone ring; beep] Lou Giansante: My name is Lou Giansante. In the early 1980s, I was doing a lot of sound recording in New York City. In October of 1982, I went to the World Trade Center to record. I went up to the observation deck, on the top, with an elevator full of tourists, and I recorded the taped message we heard as we went up. And then up on the top, I interviewed people from all over the world. The sounds of the different languages seemed important to the sound of the place. [tourists from Giansante's recordings] European Woman: Real, modern. Egyptian Man: It's for me now, you know, I can't believe my eyes, you know? European Woman: Impossible, imagine. Egyptian Man: It's like I'm come to see from Egypt, what the civilization of American people. Giansante: What do you think? Egyptian Man: I can't think! It's very important, very good. Egyptian Man two: It's for me something incredible, unbelievable. And when we go back to Egypt, I'm going to say for my friends, I see something like pyramids, you know? Did you hear about pyramids in Egypt? Giansante: And then I left with another elevator full of tourists. And at the time I remember thinking, I wish that baby wasn't crying. It's spoiling the recording. [baby crying] But now, today, listening to it, I think it sounds just right. [phone ring; beep] Voice Mail Operator: received at 9:20 p.m. November 8. Ben Cheah: Hi, my name is Ben Cheah, and I'm a sound-effects recordist. I happened to be recording elevators at the World Trade Center around about two weeks before September 11. And I have pristine recordings of the elevators. I'd be happy to contribute these recordings. [sound from Twin Towers elevators] My name is Ben Cheah and I was hired to record some sound for a movie. It involves a scene where Al Pacino takes a long elevator ride up to, within the World Trade Center. And discovers this opium den. This is the sound. A team of elevator mechanics were moving the hatch from one of the shorter elevator runs so we could actually record the elevator but inside the shaft as the elevator was traveling and uh these guys were actually riding on top of the elevator. It was pretty wild. I remember thinking that with my recordings, how little conversation that there is in-between recording takes between the elevator and how disappointed I was that I didn't roll on more discussion that was going on in the meantime. Getting more memories of the elevator operators and so forth. People created the World Trade Center. I mean obviously it was a masterpiece in engineering and architecture, but like any community, environment or building or office space, it's all about the people and that's where the memories lie I think. Man Moving Hatch: You gotta pick it up a little. There you go. [beep] Woman Caller: Hi. What I'm hoping you'll find from someone is the sound of the revolving doors in the World Trade Center. And it always struck me how they beat like heartbeats. There was this thump-thump, thump-thump, thump-thump. This life beat. [recording of Twin Towers revolving doors] Tozzoli: In the many years that my office was there on the 77 floor of North Tower, one of my great joys was to walk around. Remember, a quarter-of-a-million people passed through the Trade Center every day. Auster: Guy Tozzoli, president of the World Trade Center organization. Tozzoli: Within the World Trade Center of New York, each day 250,000 people, and many of them were tourists and visitors from other parts of the country or from other parts of the world. And you'd watch them walking through the lobbies, sitting on the plaza in the sun, listening to some of the concerts that we had. [Music for Bowed Piano, Stephen Scott and the Bowed Piano Ensemble] [This Little Light Of Mine, Odetta] Auster: Odetta performing at the World Trade Center Plaza on July 27, 2001. Hilary North worked at the Aon Corporation on the 103 floor of Two World Trade Center. Hilary wrote this poem. Hillary North: Okay. The poem is called "How My Life Has Changed." I can no longer flirt with Lou. I can no longer dance with Myra. I can no longer eat brownies with Suzanne Y. I can no longer meet the deadline with Mark. I can no longer talk to George about his daughter. I can no longer drink coffee with Rich. I can no longer make a good impression on Chris. I can no longer smile at Paul. I can no longer hold the door open for Tony. I can no longer confide in Lisa. I can no longer complain about Gary. I can no longer work on a project with Donna R. I can no longer get to know Yolanda. I can no longer call the client with Nick. I can no longer contribute to the book drive organized by Karen. I can no longer hang out with Millie. I can no longer give career advice to Suzanne P. I can no longer laugh with Donna G. I can no longer watch Mary Ellen cut through the bullshit. I can no longer drink beer with Paul. I can no longer have a meeting with Dave W. I can no longer leave a message with Andrea. I can no longer gossip with Anna. I can no longer run in to Dave P. at the vending machine. I can no longer call Steve about my computer. I can no longer compliment Lorenzo. I can no longer hear Herman's voice. I can no longer see the incredible view from the 103 floor. I can no longer take my life for granted. [phone ring; beep] Ben Ruben: Hi, it's Ben Ruben. A few weeks before September 11, I went to the World Trade Center to see a concert by Glen Branca. I think the piece was called Hallucination City. It was a symphony for 100 electric guitars. It's actually the only concert I ever got to see on the plaza of the World Trade Centers and it started off as this slow build with drums and gradually the guitar sound grew and grew. And all the while, for me the most interesting thing was just to walk on the periphery and listen to the reflections of the sound. It almost felt like you could hear the shapes of the buildings on the surfaces by listening to the way the drums and guitars echoed off of these huge flat planes in this plaza. [live recording: Symphony Of 100 Guitars, Glenn Blanca] John Peters: [Archival interview] For the record, your name, where you were born and how you became an architect. Minoru Yamasaki: My name is Minoru Yamasaki. I was born in 1912 in Seattle. Well, my parents came to the United States just a few years before I was born. Peters: I see. Auster: Minoru Yamasaki, the architect who designed the World Trade Center, was interviewed in 1960 by John Peters. Peters: What is the case for the World Trade Center? Yamasaki: I think beyond just getting people together, the Port Authority wanted to focus attention on world trade. I felt this way about it, that if we're going to build this many square feet, we shouldn't build a low or uninteresting structure. I didn't think we were going to go that high, but I thought we should have a quality about it that would interpret the fact that world trade could mean world peace. Peters: Uh-huh. Yamasaki: It was terribly important it was just not another office building. Tozzoli: Mr. Yamasaki worked in models. He did 50 different schemes. One building, ten buildings, 12 buildings on a 16 acre site, Okay? And I gave him a program, so many feet of office space, 15 million square feet total. So Yama's working on his model and he says he likes the twin towers scheme. And I said, well it looks pretty good with the plaza which is almost the size of Piazza San Marco in Venice, and I say, Yama, does it meet my program? No, he says, it's two million feet short. I say, why is that? He said, You can't build a building taller than 80 floors. And I say, Yama, President Kennedy's going to put a man on the moon! Archival News Broadcast: I have a very queasy feeling in my stomach right now because I'm at 1,500 feet. There is somebody out there on a tightrope walk between the two towers of the World Trade Center, right at the tippy top. Charles Gibson: [Archival broadcast] These are the towers of New York's World Trade Center. They are 1,350 feet high. And this morning, a young Frenchman named Philippe Petit, an accomplished aerialist who can't resist heights walked a tight wire from tower to tower. Philippe Petit: I love to go the high wire. You're never sure that you will do it because the wind was big, the wire was shaking a lot, you know." Reporter: Why did you do this? Petit: There is no why. Because, when I see a beautiful place to put my wire, I cannot resist. Tozzoli: Philippe Petit. He really planned like one would plan a bank heist almost. And he showed up in my office and said, I'm a French journalist and these two people are my assistants. So he came back to see me day after day. Somehow or another, whenever we'd talk, he constantly got back to the question of how do these buildings move in the wind? Petit: I spent actually nine years of my life organizing secretly this illegal walk. How can I bring three tons of equipment in one of the most guarded buildings in America, rig the wires, which takes three or four days, and not get shot and not get caught? And the wind and the moving buildings. Tozzoli: They used an old cross-bow and then he shot the cord across the chasm, as I call it, from one end to the other and they would attach it to the window washing device. Petit: The first step is the one where you unglue yourself from the building and you have decided to play this moment of your life - I could feel the wind. I could also feel the vibration, you know, the breathing of the Twin Towers because of the difference of temperature, they breathe, they move. They don't really sway to the human eye, but I can assure you, I remember vividly some kind of vibration at times on my wire as I was dancing and even laying down between those towers. [wind through the towers] My perception of everything was very strange. I think I was completely in another world, you know? So what I was hearing, I wasn't really hearing the way you hear something. It was more like a feeling of sound. And I did hear in that soup of sound I did hear boats, sirens of boats, beautiful, leaving for a far away country, and crazy sirens of New York police and ambulances and I did hear a wave sound that I'm sure was traffic stopping and the crowd looking up. [structural recording of Twin Towers] Leslie Robertson: Often, buildings speak to you. What happens in a tall building is that in the wind, as the building moves, the floor above moves with respect to the floor below. My full name is Leslie E. Robertson. I'm a structural engineer, and I was responsible for the design of the World Trade Center. This cassette tape is one of many that we took during the construction and later occupation of the building. For each cycle of oscillation of the building, you can hear two creaky noises, and therefore if you have a tape of it, you can measure rather precisely the frequency of oscillation of the building itself. It takes 10 seconds for the World Trade Center to go through one cycle of oscillation. [archival recording] This concludes the recording at the 67 floor, Tower A projection room. Olivia Virazzi Zadanowitz: I just got so into the building, talking about going down 70 feet to bedrock, the sky lobby system that they use, the slurry trench system that they use. I'm Olivia Virazzi Zadanowitz, and I was a construction guide for the World Trade Center during the summers of 1968, '69 and 1970. Sandy Austin Asbury: My name is Sandy Austin Asbury. I'm an FBI agent here in Pierre, South Dakota. I was a construction guide at the World Trade Center in the summers 1968, '69, '70. On their lunch hour, people would stand at these fences eating their sandwiches and looking at the unbelievable hole that was going to become the World Trade Center. The guides were a very good public relations move to get some enthusiasm over what this was going to mean to the whole look of Manhattan. We'd sit out in booths on Church Street that were elevated up a couple steps. We couldn't just stand on the street corner and hand out a pamphlet because we could get run over by the crowds of people coming out of the subways. So they gave us a little blue-and-white booth. And I remembered this little, wizened, weather-faced little carnation seller, and he kind of looked like a Popeye. He would walk up and give each one of us fresh carnations every day. He was one of the first people I thought of when I heard about the Trade Center collapsing. [Bus Talk, Bobby Watson] Archival Radio Broadcast: All news all the time. This is 1010 WINS. You give us 22 minutes, we'll give you the world. Lee Harris: Good morning; 64 degrees at 8:00. It's Tuesday, September 11. I'm Lee Harris. Here's what's happening. It's primary day, and the polls are open in New York City. Voters are deciding among about 250 candidates for mayor, city council. Meteorologist: It's going to be a beautiful day today, sunshine throughout. Really a splendid September day. The afternoon temperature about 80 degrees. [beep] Steven Manning: [message] Hello. My name is Steven Manning. I headed downtown at 8:00 on that day, and I was on my way to buy the new Bob Dylan record, which had just been released that day. And I wanted to pick it up at J&R Music World, a few blocks down from the World Trade Center. I emerged from the Chambers Street subway when I heard a deafening roar overhead, and I wheeled around, looked up and saw the first jetliner plow into the Trade Center. And I had my tape recorder with me because I was going uptown to do an interview later in the day. I turned it on. I raced towards the Twin Towers. We heard this unbelievable sound, and looked up and I saw that Tower One was cracking open. [Sugar Babe, Bob Dylan] News Broadcaster #1: The whole building just fell down. The entire World Trade Center is collapsing. News Broadcaster #2: We just had an airplane crash directly into the Pentagon. Man: Attention, 68 Engine, 35 Engine, 50 Engine, 64 Engine, 94 Engine, 83 Engine. Those units going to the - [Sugar Babe, Bob Dylan] Suarez: You're listening to The Sonic Memorial project, I'm Ray Suarez. Our program continues in just a moment, from American Public Media. Segment C: Suarez: I'm Ray Suarez. You're listening to a special fifth-anniversary rebroadcast of The Sonic Memorial project, from American Public Media. Voice Mail Operator: Message five, received September 11 at 8:59 am. Sean Rooney: [home answering machine message] Hey, Beverly, this is Sean. In case you get this message, there's been an explosion in World Trade One. That's the other building. It looks like a plane struck it. It's on fire at about the 90th floor, and it's horrible. Bye. [beep] Voice Mail Operator: Received September 11 at 9:02 AM. Rooney: [home answering machine message] Yeah, honey. This is Sean again. Looks like we'll be in this tower for a while. Building Announcement: The situation occurred in building one. Rooney: It's secure here, but. Building Announcement: The conditions are on your floor, you may wish to start an orderly evacuation. Rooney: I'll talk to you later. Bye. Auster: Julia Sweeney sent us this message from her husband Brian, who was on United Flight 175 from Boston to Los Angeles on Tuesday morning, September ll. Brian Sweeney: [home answering machine message] Jules, this is Brian. Listen, I'm on an airplane that's been hijacked. If things don't go well, and it's not looking good, I just want you to know I absolutely love you. I want you to feel good, go have some good times. Same to my parents and everybody. And I just totally love you and I'll see you when you get here. Bye, Babe. Hope I call you. Auster: Julia sent us this note with her tape. "These are the words in case they are hard to understand. Hey Jules, this is Brian. Listen, I'm on an airplane that's been hijacked. If things don't go well, and it's not looking good, I just want you to know I absolutely love you. I want you to do good, go have good times. The same to my parents and everybody. And I just totally love you and I'll see you when you get here. Bye, Babe. I hope I call you." Herb Ouida: I was sitting at my desk on the 77th floor when the plane hit. And my immediate thought was for my son; he was on the 105th floor. And my thought was that he would survive, that the firemen, whom I heard on the stairs, would be able to rescue him. I'm Herb Ouida. I'm the executive vice president of the World Trade Centers Association. I was there in 1993 on February 26 at 12:18. The bomb went off in the truck in the basement. It was much worse. I knew it was much worse. It took me one hour to get out of that building. I kept thinking, he's 28 floors above me. I got out at 10 to 10. The building didn't collapse till 10:28. He's in the same building working for Cantor. My son had no chance. Everybody in Cantor died, 658 people. Nobody above the 92 floor lived in the World Trade Center in the North Tower. What I hear all the time is my son. He was born on May 18 1976. He would have been 26 years old. Ouida Family Member: [home recording] So, now let's make a toast to the two happiest people in the world, Heather and Jordan. It seems like just yesterday, Jordan, we were outside in front of our house playing basketball. We never did get to play very much because one of us would always get loud and curse and then Dad would yell at us and make us come inside. Ouida: We decided, my wife and I, that we were going to set up a foundation, because he had a problem as a child. He suffered from panic attacks. So we want to help any child that has a psychological difficulty. My church has asked me, they want to make a plaque for my son, and they asked me the other day if it's all right to put the World Trade Center on the plaque. And I said, "No. I loved those buildings. I worked there." It just becomes very hard for me personally. And yet, I'm part of an association that promotes the concept of World Trade Centers. That's what I do. And I believe in that concept because the concept is completely opposite of what these people did on that day. I'm from Lebanese background. I'm from the Middle East. My family's from the Middle East. I had so much hatred for these people, and I found it was consuming me. It really was not good for me to have so much hatred. The only answer is, if you can make some good out of an evil, help somebody else, maybe, maybe you'll have a little peace. [bells ringing at mosque; man in mosque singing] Auster: A prayer service at the Atlantic Mosque in Brooklyn. Egyptian Man: I've been here since 1980, in this area. Auster: What's your home country? Egyptian Man: Egypt. I'm a member of the mosque and also I have my business in the middle of the block here. One of my friends who died, he used to work in security at the World Trade Center and this is our loss, too. It's our loss, too. We should be united - Muslim, Christian, Jew, Hindu. We're all of us supposed to be united, to overcome and rebuild our city once again. [R.I.P, Colin Trip and Eric Miner] Voice Mail Operator: Message 22 was received at 2:00 pm, December 3. Colin Travers: Hello. My name is Colin Travers. A friend brought my attention to this sonic memorial you guys are putting together and actually a friend of mine, Eric Miner, and myself created in the two weeks following the 11th a "World Trade Center Dedication" piece. It's basically a hip-hop, using samples from MSNBC, films, as well as basically scratching in samples from records. We would like to contribute to this because I know we poured our hearts into it and it definitely meant a lot to us. Martin Luther King Jr: [sampled audio from R.I.P] Violence is wrong in America. Violence is wrong abroad. Robertson: No matter how good a job we do at mending fences, trying to bring peace to the world, we're going to have to live with a segment of the world that's extremely angry with the United States and with other parts of the world. And we're going to have to live with that for a very long time. The people who did this had lived in our midst, they'd seen our lawns and our kids and knew a lot about us, and still carried a hatred that's deep enough so that they'd give their lives. Leslie E. Robertston. I was the chief engineer. I headed the design of the structural system for the building. I do wake up with the thoughts in my head. But we cannot possibly close the doors on all the targets. We cannot make the planes or the buildings suitable to resist these events. I'm not a believer in hardening buildings, and I think it's a wrong way to think about life. [Come Softly, The Chantels] Voice Mail Operator: Message 29 was received at 7:30 a.m. Friday. Beverly Eckert: This is Beverly Eckert. My husband Sean Rooney was killed on September 11 at the World Trade Center. And my story about sound starts this February when Sean turned 50. My sister made a special CD for him. I gave her a list of songs that I thought were either Sean's favorite songs or were part of the story of his life. We met when we were 16, and being together with somebody that long you know what songs they like. The tape starts out with "Come Softly" and starts out with [Eckert hums]. And I remember when we first played it for Sean, you know when he got the CD and just the smile on his face when he heard that song. Oh, and there's several songs on there. Theme from a summer play, "Town Without Pity." When Sean and I were 16, of course nobody thought it could possibly last so the adults of the world gave us quite a hard time. And we were right because we stayed together for 34 years. And "You Make Me So Very Happy," that has special meaning to me because I did get to say goodbye to Sean on the phone just before the building collapsed and I did tell him that he made me so very happy. [phone ring; beep] Nikki Stern: [message] My name is Nikki Stern. My husband of 11 years, Jim Fattorti, was killed at the World Trade Center on September 11. I got a lot of grief books early on. I think people were trying to figure out what to do to help me. And all of the grief books marked stages - Okay, first you're going to be numb, then you're going to be mad, then you're going to be this - it completely doesn't work that way. All five emotions and three others you didn't even know existed hit you all at once. And then there's a lull where you can almost function, so you do that. And then another tidal wave comes and hits you. The widows in particular, we always talk about, does this make sense? Or is anybody else besides me feeling this way? Or, I laughed today. Is it Okay that I laughed? I am always going to be faced with the sight of the towers. We're all just going to keep seeing - it's going to be in the history books. That has to go into a mental picture along with my discussions with the medical examiner's office, and all that has to be put together in a picture book and stored somewhere. I don't know where yet. [Sonic Memorial Project Sonic Signature] Kenneth T. Jackson: I'm Kenneth T. Jackson, I'm a professor of history at Columbia University, and the director of the New York Historical Society. There's an assumption that no matter whatever happens to the 16 acres of the World Trade Center, there will be a memorial or a monument to the 3,000 people who lost their lives there. A hundred and more years ago, that was never an assumption that somehow you'd build a monument or memorial to people. Even battlefields - Waterloo, Gettysburg - were not immediately transformed into places of veneration and respect. Before the World Trade Center collapsed, the worst tragedy in New York history was the burning of an excursion ship called the General Slocum, which was filled with women and children. A little over 1,100 people in June 1904 when it caught fire on the East River. What are the memorials to the General Slocum? Well, there's a little, kind of unimpressive monument in Tompkins Square Park. Or the Triangle Shirt Waist Fire, which is one of America's best known tragedies, where 146 mostly Italian and Jewish young women, mostly between the ages of 15 and 25 perished one day jumping from the windows of the building, which is important to American history because it led to changes in factory laws around the country. You couldn't lock people in when they were at work. What do we remember about the Triangle Shirt Waist? There's a plaque. And it's maybe 2-feet-by-2-feet on the side of the building. And that's it. What's ironic is that 100 years ago, when they didn't think in terms of these group memorials, but they did sanctify death in yet another way, in the cemeteries. And visiting cemeteries were really an important event. And whole families went, and they felt that they were communing not only with the dead person, but with God and then also with nature. Now in our time, when we don't go to cemeteries anymore. Cemeteries are really isolated and almost scary places because they're so empty. Now we're drawn toward these kind of these public memorials, whether it's the Vietnam Memorial in Washington or, you know, something else. And one of the things about the World Trade Center and the neighborhood before the World Trade Center reminds us to do is look around us now, look around at the old stores, the little stores, the big stores and to remember what you see. I think it reminds us that we need to treasure the people we know, we need to treasure the neighborhoods we live in. All the relationships. Everything is important. Look at it, remember it, try to file it away because nothing is forever. [Sonic Memorial Project Sonic Signature] Voice Mail Operator: You have 64 new messages. Message 1 was received at 11 pm. [This Little Light of Mine, Odetta] Suarez: You've been listening to "The Sonic Memorial Project," originally produced for the first anniversary in 2002. The Sonic Memorial was written and produced by The Kitchen Sisters: Davia Nelson and Nikki Silva; with Ben Shapiro, Jamie York, Jay Allison and Joe Richman in collaboration with a gathering of radio producers, listeners, archivists, historians, New Yorkers, among others. Paul Auster narrated the program. The Sonic Memorial Project is a collaboration between Lost & Found Sound, NPR, WNYC, Picture Projects and independent radio producers nationwide. Major funding comes from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting and the National Endowment for the Arts. Additional support comes from the Ford Foundation, Minnesota Public Radio and listener contributions to The Kitchen Sisters Productions. Project travel was provided by a generous donation from Jet Blue. For more on this project, visit sonicmemorial.org, where you'll find an archive of the images and sounds of the World Trade Center. You can also get there from americanradioworks.org. American RadioWorks, the documentary unit of American Public Media, is funded by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting. | ||