|

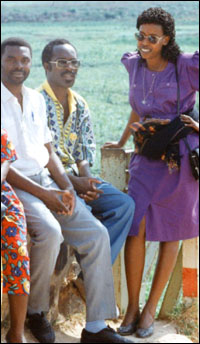

| Callixte Mbarushimana (center)

photo courtesy of Jon Swain |

Callixte Mbarushimana says he had nothing to do with the genocide. In fact, Mbarushimana's account of his time during the 100-day slaughter of 800,000 Tutsis depicts a man who risked his own life to save the lives of others. Speaking through his American and French attorneys, Mbarushimana recounts braving militia barricades to help deliver food, water and money to his colleagues at United Nations Development Program (UNDP) who were trapped by the violence.

But genocide survivors have a starkly different view of Mbarushimana's history. At the start of the genocide in April 1994, they say Mbarushimana became a gun-toting militia chief who helped hunt down and kill Tutsis, including U.N. co-workers. Survivors and former U.N. colleagues also say Mbarushimana offered army officers and militia leaders technical assistance that made the killing even more efficient: U.N. vehicles, satellite phones and personnel files of some U.N. workers suspected of sympathizing with Tutsis.

"Wherever Callixte went, the next day people would be found dead," says Donita Mukabalisa, a former UNDP worker who is now a member of Rwanda's parliament.

Current and former U.N. officials and war crimes investigators say witnesses have linked Mbarushimana to numerous massacres in Kigali, the Rwandan capital. They also say the U.N.'s failure to promptly pursue allegations against Mbarushimana allowed him to keep working off-and-on for the organization for nearly ten years after the genocide.

Former colleagues say Callixte Mbarushimana's hostility toward Tutsis surfaced long before the genocide. Mbarushimana was born in 1963 in a northern region of Rwanda that was a stronghold of Hutu extremism. It was a tumultuous period for the country and its two main groups, the majority Hutus and minority Tutsis, who comprised about ten percent of the population prior to the genocide. Rwanda's colonial rulers had favored the Tutsis, giving them preferred posts in business and government and encouraging Tutsi prejudice against the lower-caste Hutus. At independence, Hutus took both power and revenge, killing thousands of Tutsis and driving tens of thousands into exile.

In 1990, a rebel army made up largely of exiled Tutsis invaded Rwanda and triggered civil war. They called themselves the Rwanda Patriotic Front (RPF). The Tutsi rebels vowed to end Hutu domination and one-party repression, but the RPF invasion had the opposite effect. Hutu strongman Juvenal Habyarimana's regime tortured and murdered thousands of Tutsis accused of sympathizing with the rebel cause.

In the midst of the civil war, Callixte Mbarushimana was hired by the UNDP in 1992 to manage the agency's computer network for its expanding country operations. The UNDP was the lead U.N. agency, overseeing a wide variety of development projects. Relations between Tutsis and Hutus on the U.N. staff were under tremendous strain despite the appearance of collegiality

"At the time, we still entertained the myth of the U.N. as a big happy family," recalls Bisa Samari, a Rwandan economist who worked alongside Mbarushimana at the UNDP. "Of course, later on, we became painfully aware that it was only a myth. But despite our efforts, unfortunately, the sense of mistrust continued to grow."

Samari remembers Mbarushimana as a quiet and competent computer technician. But as the war intensified, Samari says Mbarushimana's attitude towards Tutsis became more apparent. Samari and Donita Mukabalisa recall hearing Mbarushimana angrily refer to Tutsis as "inyenzi" a pejorative used by extremists that means "cockroach." Though U.N. staff was expected to avoid politics, Samari noticed Mbarushimana was seen in public with men who were part of President Habyarimana's security apparatus.

"To Callixte, people were either good or evil and that was that," says Samari. "As with other people who have simplistic views, very often they are used by violent systems because it's easy to tell them, 'You are defending a good cause, the Hutu cause.' So, he had a relatively limited intelligence for political analysis, and he was not alone. In this country, many others fell in the same trap, simply because they had been raised in the belief that the Tutsis were bad."

|