|

Book Excerpts

Alexander Radishev's impassioned plea for reform

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

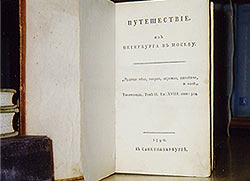

Original 1790 edition of Radishchev's Journey from St. Petersburg to Moscow. Click to enlarge

Photo: Rob Rand |

|

|

Radishchev's Journey from St. Petersburg to Moscow describes the political, economic, and social conditions of Russia in the 1780's,

during the reign of Catharine the Great. Radishchev's primary target is the negative impact the authoritarian ruling regime had on the peasantry, who worked the fields as serfs for the landed gentry. He disparages the lack of democracy in Russia and attacks the privileges of the wealthy. The book portrays the breadth of poverty in Russia among the peasantry. It condemns the absence of a free press and attacks censorship. It rails against uncaring and arrogant state bureaucrats. It criticizes an unfair system of justice. And mostly, it calls for reforms: for liberty and a system of government in which all men and women are free and equal and in which serfdom is abolished. While the Russia of Catherine the Great is separated by some 200 years from the Russia of Vladimir Putin, the themes that Radishchev wrote about resonate today.

In Radishchev's peasant one can see the majority of contemporary Russians, especially those in the countryside, who have not reaped much benefit from the free market. In Radishchev's wealthy and arrogant landed gentry one can see the minority of free marketeers who have profited from the collapse of communism, especially the post-Soviet oligarchs who control so much of Russia's wealth. The lying and corrupt and uncaring bureaucrats in Radishchev's book are still around today. And just as Radishchev lamented injustice and the lack of citizenship, so do today's reformers call for a "law based state" and a civil society.

Here are a few samples from Radishchev's Journey From St. Petersburg to Moscow:

A citizen's right to question |

The Russian tune: soft and melancholy |

The poverty of a peasant's home |

The corruption of wealth

A citizen's right to question

In the following excerpt, Radishchev argues that men voluntarily submit to governmental authority in order to gain advantage in their personal lives. If the government does not provide that advantage, then citizens have the right to question the legitimacy of the government. For the large majority of contemporary Russians, those who have been left behind by the post-soviet free market, Radishchev's thinking makes a lot of sense:

"Every man is born into the world equal to all others. All have the same bodily parts, all have reason and will. Consequently, apart from his relation to society, man is a being that depends on no one in his actions. But he puts limits to his own freedom of action, he agrees not to follow only his own will in everything, he subjects himself to the commands of his equals: In a word, he becomes a citizen. For what reason does he control his passions? Why does he set up a governing authority over himself? Why, though free to seek fulfillment of his will, does he confine himself within the bounds of obedience? For his own advantage, reason will say; for his own advantage, inner feeling will say; for his own advantage, wise legislation will say. Consequently, whenever being a citizen is not to his advantage, he is not a citizen. Consequently, whoever seeks to rob him of the advantages of citizenship is his enemy. Against his enemy he seeks protection and satisfaction in the law. If the law is unable or unwilling to protect him, or if its power cannot furnish him immediate aid in the face of clear and present danger, then the citizen has recourse to the natural law of self-defense, self-preservation, and well-being."

The Russian tune: soft and melancholy

Radishchev's driver sings a Russian folk song, and Radishchev hears the strains of the Russian character. The tune is as fresh today as it was 200 years ago, and Radishchev's phrase, "impulsive, daring, quarrelsome," is an apt description of contemporary Russian politics:

"The horses carry me quickly, and my driver has started a song, as usual a melancholy one. He who knows the melodies of Russian folk songs must admit that there is something in them which suggests spiritual sorrow. Nearly all the tunes of such songs are soft and melancholy. We have learned how to establish governmental rule in accord with this musical inclination of the people. In these songs you may discover the very soul of our people. Look at a Russian: you will find him pensive. If he wishes to purge his melancholy, or, as he would say, to have a good time, he goes to the tavern. In his pleasures he is impulsive, daring, quarrelsome..."

The poverty of a peasant's home

Radishchev describes the poverty of a peasant's home. It provides a yardstick to measure how much conditions have or have not changed for today's rural Russians. Today Russia's reforms have not improved the standard of living of most of Russia's people, and many of those impoverished contemporary Russians will blame their poverty on the greed, rapaciousness, and tyranny of those who have prospered by capitalism:

"The upper half of the four walls, and the whole ceiling, were covered with soot. The floor was full of cracks and covered with dirt at least two inches thick; the oven without a smoke-stack, but their best protection against the cold; and smoke filling the hut every morning, winter and summer; window holes over which were stretched bladders which admitted a dim light at noon time; two or three pots (happy the hut if one of them each day contains some watery cabbage soup!). Here one justly looks for the source of the country's wealth, power, and might. But here are also seen the weakness, inadequacy, and abuse of the laws: their harsh side, so to speak. Here may be seen the greed of the gentry, our rapaciousness and tyranny; and the helplessness of the poor."

The corruption of wealth

Radishchev tells the story of a Russian official whose actions were motivated by the desire to eat oysters. It's a metaphor for corruption and self-centered accumulation of wealth, issues very much present in Russia today:

"As soon as he began to climb up the ladder of ranks, the number of oysters at his table began to increase. And when he became Viceroy and had a lot of his own money and government funds at his disposal, he craved oysters like a pregnant woman. Asleep or awake, he thought only of eating oysters. While they were in season nobody had any rest. All his subordinates became martyrs. No matter what happened, he had to have oysters. He would send an order to the office to furnish him a courier at once, to dispatch with important reports to Petersburg. Everybody knew that the courier was sent to fetch oysters, but he had his traveling expenses granted anyhow."

Reprinted by permission of the publisher from Aleksandr Radischev's A JOURNEY FROM ST. PETERSBURG TO MOSCOW, translated

by Leo Wiener and edited by Roderick Page Thaler, Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, Copyright © 1958

by the President and Fellows of Harvard College.

|