|

| ||

|

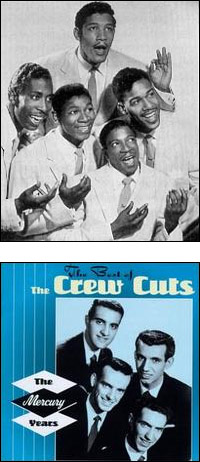

Sex, Race and Rock & Roll part 1, 2 If adult America was in an uproar about the dangers they heard in R&B and rock and roll, teenagers like Bruce Morrow were hearing other things. "With Alan Freed coming in," says Morrow, "all of a sudden we were hearing people like Big Joe Turner, Mama Thornton, Ray Charles was coming into our lives. And we started identifying with this music. And the music was saying things, talking about what was happening in lives of people we didn't really know because they didn't live in our neighborhood, in our world. Music gave us the opportunity to become human beings." "White people listening to African American music on the radio has played an underappreciated role in having white people first embrace black culture and then begin to appreciate that there were commonalties. And that forged an important beginning bridge between the races," says Susan Douglas. She points out that some corners of American society, of course, wanted to keep that bridge from being built. They wanted to keep the music that they saw as sexualized and morally corrosive off the air. But, in some ways, they shouldn't have worried because big business was already finding ways to make a buck by stripping the music of its danger. Around 1954, Chuck Blore was working as a DJ in Arizona.  The Chords (above) originated the song Sh-Boom. The Crew-Cuts (below) had the mainstream hit. "I remember, there was a record, I was still in Tuscon. The record was 'Sh-boom.'" The original version was by the Chords. Five African American guys from the Bronx. "And that record, oh God I loved it. And then of course, the guy from Mercury came in and said 'Don't play that version. Play our version,' and we said 'Oh! Okay!'" which was by the Crew-Cuts, four, clean cut, white guys from Canada. "Here's African American music and young white teenagers loving it," says Rick Wright. "All the music was covered. I mean Little Richard would do a version of "Tutti Frutti" which was the original. It got no air play at all. Then it was covered by Pat Boone." It's a familiar story. One hundred years into the history of music radio, we're used to the pattern. Mainstream corporate radio sands down rougher edged music from the underground and polishes it up for mass consumption. It happens all the time today. It happened when the networks took control in the 30s. But in the 50s, radio was suddenly a wide open industry again. With no central control. It took a certain business genius to create a homogenized sound all those local stations would embrace. Actually, it took several business geniuses, perhaps the most important, was a man named Todd Storz. The partially apocryphal story of the night Todd Storz invented Top 40 began with Storz in a diner, probably around 1949. He watched how teenagers played the jukebox. A popular song would play, and once it finished, someone would drop another nickel in the machine and start that same song again. And then the waitress would take her tips and drop them in the jukebox and play the same song over and over and over. A light bulb went on in Storz's mind about a new format. One that would replicate the way teenagers used the jukebox. If the kids want to hear what was popular, then let's give them what's popular over and over again. Advertisers loved the idea because there was never any controversy. Only the most inoffensive stuff with the broadest appeal could crack the Top 40. The format was a godsend to people worried about sex and race and rock and roll. And these powerhouse AM stations in the late 50s and early 60s pretty much wrote the play book for modern radio. The jingles, the gags, the promos, the give-aways. The sound of big commercial radio. The homogenized music manufactured to appeal to everyone while offending no one. Back in their heyday in the 60s and early 70s, top 40 stations dominated the ratings. Of course, you'll still find top 40 stations on the air today, but in some ways, they're shadows of their former selves. Their grip on listeners started to slip mid-70s. FM radio came in. Listeners liked the sound quality. Business liked that you could split the dial up into more and more stations. Susan Douglas says that with more stations came more formats. "We have top 40, we have urban, we have soft jazz and so on and so forth," says Douglas. The time when pretty much everyone was listening to the same things was over. "And what the industry will say today is, 'there's more diversity than ever. Look at all of the formats.' But within each format, you have diversity kept at bay on the other side of the door." Douglas says these narrow niches have stripped radio of some of its power. "And this move seeks to place each of us in a very narrow preserve where we don't have to listen to other kinds of music and therefore don't get exposed to other kinds of music." And new technologies push this trend even further. If you're a fan of old school R&B, you can catch Rick Wright on Power 106.9 if you're in Syracuse, New York. Or you can listen anywhere, on the Web, where you can pretty much find anything else you want, whenever you want it. New technologies mean everyone can find the kind of music they like. If radio used to provide a turnstile between different racial and social groups, now it sets up walls between them. The days when a whole culture could be moved, and maybe even moved a bit forward, by new music and new voices on the radio might be over. In this time of satellite radio and podcasting and Internet radio and multi-stream High Definition radio, it's maybe too easy to listen to exactly what you want to hear. And hear the sounds of music and of people you already know. Back to Hearing America |

||