|

| ||

|

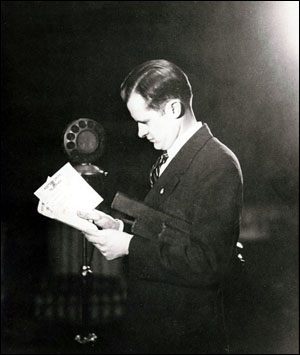

New York Clashes with the Heartland part 1, 2  Radio broadcast from the Chicago Opera, circa 1921 - Courtesy Library of Congress By 1930, networks linked radio stations from coast to coast. The sounds of high-brow New York culture became the default soundtrack to American life. Its symphonies, its Broadway show tunes, even its tap dancing. Some music simply vanished from the air. Gone was the stuff that caused so much turmoil in the 1920s - the hot jazz of night clubs and dance floors and saxophones. The network era was almost aggressively civil. "All staff people had to wear tuxedos after 6 p.m.," says Ben Grauer, a popular voice on NBC for decades. "The dominant note was one of cautious formality with the listener. The doctrine was that you were a guest in the home. The earliest hosts or masters of ceremony were very square, they had to be. The idea was you were the spokesman for this dignified responsible, highly ethical corporation." After all, radio had earned a bit of a reputation in the pre-network years. What with its music made by foreigners and black people and hillbillies. There were rough edges that needed sanding. Most of the audience loved this new national programming from NBC and CBS. They'd been listening to amateurish local stations with fourth rate dance bands for years and now there were high quality productions coming in with a clear signal. But author Cliff Doerksen says there was a major audience left out. "Rural people in the 20s had their own stations called farmer stations," says Doerksen. "They didn't like what came out of the cities, they didn't want to hear the classical music and opera coming from the high brow stations. And they sure didn't want to listen to jazz from the low brow stations. They wanted to listen to what was called 'old-time' music." Old-time, sort of a grab bag category of fiddle music and old pop tunes that were so far behind the time that they had become folk songs. But with the New York-based networks running the show, these stations and this music almost disappeared completely from the air. Almost. The federal government wanted everyone in America to have access to national programming. But it knew it wasn't in the networks best interest to buy a little 200-watt station in every hill or holler to make that possible. So Washington allowed for what were called Clear Channel Stations. These were powerful stations in cities whose broadcasts could reach out into people's homes in the countryside.  George D. Hay, original annoucer of WSM's "Barn Dance" and later "The Grand Ole Opry," known to his listeners as "The Solemn Old Judge" - Courtesy Grand Ole Opry Museum And on a few of those stations, old-time music found champions. Perhaps none was more important than George D. Hay who created the Grand Ole Opry. He started out as a newspaper man. Had a popular column called Howdy Judge in the Memphis Commercial Appeal. A lot of the articles were fictional accounts of African Americans appearing in court before a white judge. The same kind of racist jokes that were in some of the minstrel acts he later brought to radio. Hay was an early host of the WLS Barn Dance, an Old Time music program on a powerful Chicago station. "He created this persona for himself called the solemn old judge," says John Rumble, senior historian at the Country Music Hall of Fame. "He dressed in an old fashioned flowing tie and a swallow tail coat, he had a little, wooden whistle that would recreate the sound of a steamboat whistle. And he would blow that to begin the country programs. Hay's career took off when he moved down to start up another program on Nashville's WSM. The station mostly played New York stuff from the network. "So in 1925 he organized what was then called the WSM barn dance," says Rumble. "Which was fortuitously and serendipitously renamed the Grand Ole Opry in 1927." The "night the Opry got its name" is one of the classic origin stories in American pop culture history. "The Opry got its name one Saturday evening in 1927," says historian Louis Kyriakoudes. "Over the radio from New York, on the national broadcast feed, was the New York Philharmonic. Walter Damrosch was the conductor and he told the audience that there was no place in the classics for realism, but that he would make an exception and perform a piece by Arthur Honegger called Pacific 231, which sought to recreate the sounds of a train. George D. Hay in Nashville, waiting for the orchestral concert to end, said, 'For the next three hours, we will present nothing but realism. We will be down to earth for the earthy. We have heard grand opera from New York, but now we will be listening to the Grand Ole Opry.' And there upon, DeFord Bailey, the harmonica virtuoso on the program, launched into his Pan American Blues." Hay was trying to create, and create is the key point, a radio program and a style of music that appealed to the predominantly rural and small town audience. So he was really juxtaposing the collection of string band musicians and odd performers from Vaudeville who would show up in the early years of the Opry, against this vision of high culture being broadcast over the New York based radio station.  Members of the Bog Trotters Band - Courtesy Library of Congress Hay played what you could call the Hillbilly card. He gave his popular performers names that would sound more authentically Southern and rural: The Fruit Jar Drinkers, The Gully Jumpers. Dr. Humphrey Bate, an actual Vanderbilt-trained physician, and his Augmented String Orchestra became Dr. Humphrey Bate and his Possum Hunters. "Hay is picking and choosing to determine who will be on the Opry and trying to present a highly rusticated vision of what Southern musical culture is," says Kyriakoudes, "and it's appealing to the people who are listening in the audience because they have one leg in each world. They have one leg in the older, really 19th-century world of the South, and for that matter, the Midwest, but then they've got one leg in the modern world. Thousands and thousands of them are leaving Southern and Midwestern agriculture, moving to cities. They're people making a transition from one way of life to another and George Hay is there presenting a manufactured rusticality that they find reassuring and comforting and fits in with really what many see as their own self identity." And that identity was white. Kyriakoudes says Hay took a biracial musical tradition and whitewashed it, creating what would come to be called country music. "The down home rural card was a good card to play," says sociologist Richard Peterson. "Because there was such fear of what was happening in the cities. There was so much race mixing, there was so much jazz, there was all kinds of degradation in music. Here was a way of finding a pure, unadulterated, American music that came out of an Anglo-Saxon background. They made up a whole bunch of stuff." Shows like the Opry and the WLS Barn Dance were usually squirreled away to just a couple of hours on the weekend, but there was one powerhouse station keeping old-time music alive all week long. How it got there is one of the most unlikely stories in the history of radio. Continue to part 2 |

||