|

Debriefing

Part 1 2 3 4

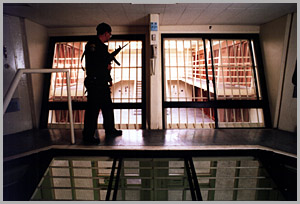

| A guard with a high powered rifle patrols the SHU - courtesy California Department of Corrections |

Inmates who buy into the debriefing program, are eventually transferred to another part of Pelican Bay, one that is a world away from the SHU. On this day, six men are playing basketball in a small gym. A guard with a high powered rifle watches from a balcony and the doors are locked, but the atmosphere is loose. Sweat pours over large tattoos stamped on the men's torsos. They are former rivals: blacks, whites and Latinos. They're in a unit for former gang members now, segregated from the general population so they won't be assaulted or killed for betraying their gangs.

"When they first take them handcuffs off no one knows what to do with their hands," says Manuel, who dropped out of a gang and left the SHU last year. "So everybody automatically puts them behind their backs or to their sides because you don't want to make a quick movement because you know ... you're still on full alert."

"When I entered the process I broke down and cried," says David, a dropout from a white gang who doesn't want his real name used for broadcast. "It was incredible to walk out and not be handcuffed and be in a room full of people or to come outside and walk around on a big yard and actually see things around you like trees and mountains. When I debriefed I hadn't seen a tree for about three and a half years."

Other men talk of not seeing the moon or stars for 20 years. Conditions here are dramatically different. Outside, on a large exercise yard, a cool wind from the Pacific blows mist over the pines and redwoods surrounding Pelican Bay. Three inmates, one white and two Latinos, are warming in the faint sunshine. They wear blue jeans and pale blue work shirts.

I asked the men what they felt when they came out of the SHU for the first time.

"Freedom. Relief," says one inmate.

"You're your own man," says another. "You're able to socialize with whom you want. Back in the day you wouldn't see me and him standing together, because we're from rival gangs."

The men go through a standard prison curriculum: classes on computers, victim awareness, parole survival and anger management. Some inmates were in the SHU so long that this is the first time they've ever handled computers. Some men have never even seen a compact disc before.

Instructor Salvador Hernandez is leading 15 men through a class called "Breaking Barriers." He talks to them about ways to control anger.

"Anger gives us energy," Hernandez explains. "It gives us a lift. That's the trip about anger."

Several inmates nod in agreement but one man shakes his head. He tells Hernandez that anger management won't stop prison violence.

"Violence is an instrument of communication in prison," the inmate says. "It's the way people communicate with one another. It's not a product of anger, it's a value judgement. Sure people deal with frustrations in prison. A lot of it has to do with hopelessness."

Continue to part 3

|