Atoms for Peace

With the onset of the Cold War in the early 1950s, the United States sought to change the image of atomic energy from a force of awesome destruction to one of peace and prosperity.

That idea that the world should benefit from peaceful applications of nuclear energy was the centerpiece of an initiative launched by President Dwight D. Eisenhower that became known as "Atoms for Peace."

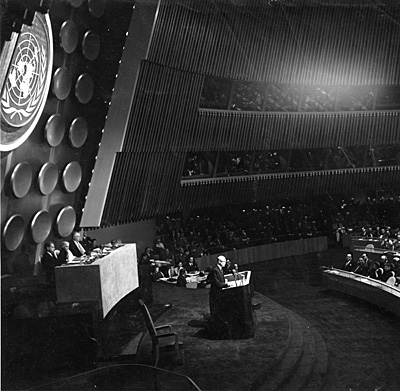

President Eisenhower delivering his Atoms for Peace speech before the U.N. General Assembly, December 8, 1953. Courtesy Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library & Museum

In a speech to the United Nations General Assembly in December 1953, Eisenhower proposed a nuclear strategy that would harness the peaceful applications of atomic energy for countries around the world. Eisenhower reached out to the Soviet Union, saying the time had come for the "two atomic colossi" to work together to build a more peaceful world. Otherwise they were "doomed malevolently to eye each other indefinitely across a trembling world."

At the core of Eisenhower's plan was a new international atomic energy agency, to be set up under the auspices of the United Nations. According to historian John Krige, Eisenhower called on the major powers, notably the United States and the Soviet Union, to "make joint contributions from their stockpile of normal uranium and fissionable materials" to the new agency. The nuclear material would then be allocated for medicine, agriculture and, above all, "to provide abundant electrical energy in the power-starved areas of the world."

The program was also a product of Cold War rivalries, notes Krige. "It was an effort to win hearts and minds and make sure that countries like India, or Iran or Israel, that wanted nuclear technology would get it from the U.S. and not be tempted to get it from the Soviet Union." Krige says the plan also opened new markets for big U.S. corporations such as General Electric and Westinghouse.

Author Catherine Collins describes Atoms for Peace as a "nuclear Marshall Plan which would promote the safe and peaceful uses of atomic energy and at the same time monitor the use of it, so it couldn't be diverted to weapons programs."

Collin notes a p.r. element at work. When the initiative was announced, the United States was engaged in a major build-up of its nuclear arsenal which included controversial tests of hydrogen bombs in the Pacific. "There was growing concern both inside the U.S. and internationally about the impact of these nuclear tests," says Collins. "So they used Atoms for Peace as a sort of distraction." Atoms for Peace allowed the great powers to maintain their nuclear monopoly while promoting the idea that nuclear energy could transform the global economy and pull developing countries out of poverty.

Krige and other historians have noted the positive legacy of Atoms for Peace. The program was successful in creating the International Atomic Energy Agency, and a web of safeguards which the IAEA imposes on member states. The initiative also planted the seeds for the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, the cornerstone in global efforts to contain the spread of nuclear weapons.

However, in some ways Atoms for Peace backfired. Several countries that received training and technology transfers through Atoms for Peace eventually used that knowledge platform for illicit weapons programs. India, Pakistan, South Africa and Israel all received direct or indirect support through Atoms for Peace. Each of these countries later built secret nuclear weapons stockpiles.

Collins writes that the chairman of India's atomic energy agency called Atoms for Peace the "bedrock on which India's nuclear program was built."

Back to Business of the Bomb.