Part 1 2 3 4 5

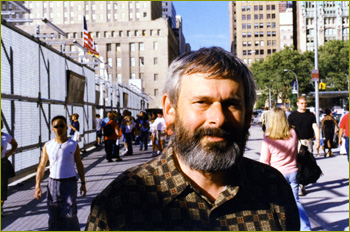

| Richart Smith, an expert and consultant on data privacy issues.

(Photo by John Biewen) |

We take a walk in New York City with Richard Smith. He's a former computer programmer, now an expert and consultant on data privacy issues.

"I think the first thing we have to say is ... this is something new, something different - that our lives are being recorded. It is like ... these electronic diaries are being kept by all these other people. ... That's new territory; we haven't been there before," says Smith.

Commercial databases don't just hold records detailing who you are, your interests and health problems, and how much money you have to spend. Increasingly, we're using electronic gadgets that actually track our movements.

"That are very much part of our life now," says Smith, "that we even take for granted. We even know they're there but we don't kind of think of them as surveillance networks."

On a Manhattan street corner, Smith points out a neglected, old-fashioned payphone. Drop in a quarter and the machine leaves a record that a call has been made, but it doesn't know who made it.

"Now with the cell phone," says Smith, "that's all out the window. This [cell] phone here is, you know, tied to your bank account, tied to your identity. The location of it - I don't see any cell phone antennas around here, but the cell phone network tracks you all the time. And, it can identify your position down to about a half a mile, maybe to a few blocks here in the city."

Smith's list of sensors goes on: ATM machines, credit card readers, the Internet, electronic fingerprint readers, those convenient tollbooths that sense transponders on cars. Smith stresses this is not the surveillance society George Orwell imagined. We feed these sensors voluntarily, just as we trade off our personal information for an array of conveniences and discounts.

The data industry emphasizes those trade-offs and rightly considers itself a central part of our information-rich economy. Jennifer Barrett is an executive with Acxiom, one of the world's biggest collectors and processors of personal information. Acxiom mainly helps companies with marketing and customer service. At her office in Little Rock, Arkansas, Barrett argues most Americans love what the data revolution does for them, without knowing how it works.

"I have a personal belief that the consumer really doesn't want to know. I don't care to know how the electricity gets to that light switch over on the wall. But when I punch that light switch, I want the lights in this room to come on, and I want them to come on pretty quick," Barrett says with a snap of her fingers. "And I think the value that information brings to the consumer is a little bit like that."

But since September 11, 2001, Acxiom, ChoicePoint and their competitors have taken on a new role as contractors in the war on terror at home.

"It's one thing," says Richard Smith, "that if Acxiom predicts you're going to buy, you know, such and such a product and somebody sends out an ad to you - junk mail piece or a telemarketer calls, and you say, 'No.' It's quite different thing when law enforcement comes to your house and says, 'We think you're ... a danger; we're going to start watching you' or something like this."

Back to No Place to Hide

|